Who Invented Idolatry?

June 2023 | Vol. 11.6

By Daniel Barbu

In late antiquity, Christian authors triumphantly celebrated the end of polytheism and idolatry: Christ had vanquished the demons and the Church taken over the empire. Both concepts, however, were relatively new, and were forged in the context of the theological debates aiming to define Christianity as the sole true religion as opposed to the multitude of religious customs, practices and beliefs of the ancient Mediterranean. The advent of a Christian empire in the fourth century did not mark the end of idolatry. Rather, it allowed the concept to spread beyond such theological debate and operate as a category of legal, political, and historical discourse. Idolatry would in fact prove an enduring concept, setting the stage for early Western explorations into comparative religion in the early modern and modern eras, when a wide range of previously unknown “idolatries” were suddenly exposed and required explanation.

Fresco from San Silvestro Chapel at Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome (1247 CE) depicting the (fictional) ‘Donation of Constantine’, whereby Emperor Constantine, having converted himself and the Empire to Christianity, offers Pope Sylvester I the imperial tiara.

In the literal sense, the Greek compound name eidōlo-latreia refers to the worship (latreia) of an idol (eidōlon). Words, however, are rarely bound by their literal meaning. Moreover, the “idol”, of which idolatry is the worship, is itself an evasive concept; the relationship between idol and image is often not as straightforward as one may hope. The first author to provide us with a definition of idolatry, Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215 CE), wrote: “Idolatry is a distributing (epinemêsis) of the One into many gods” (Clement, Stromata 3.12.8). Tertullian (c. 160–225 CE), whose role was decisive in crafting a Latin language appropriate for Christianity, considered idolatry to be a form of adultery: “for whoever serves false gods undoubtedly commits adultery against truth” (Tertullian, De Idololatria 4.1). Idolatry can thus exist even without an idol, and even preceded, in Tertullian’s opinion, the invention of arts.

For these early-Christian authors, the notion of idolatry essentially defined the human propensity to stray away from his maker and establish false religions. Idols, when they appeared, only gave their name to this universal sin. Idolatry thus appears as a plastic notion, used to outline a negative pole in opposition to which “true Religion” could be defined.

How did idolatry originate, however? The question haunts the Christian imagination of religious difference. The Hebrew Scriptures did not provide any clear explanation in this respect — as it did, for instance, regarding the multiplicity of languages and nations (thus, the Tower of Babel story). It allowed, however, framing the issue within a broader narrative of degeneration: a narrative in which the human condition is conceived of as a fall. Human history, within the framework of biblical anthropology, is the history of mankind’s degeneration from its primeval intimacy with God.

(Left): Clement of Alexandria (150 – c. 215). Engraving by Thomas Campanella de Laumessin in André Thevet, Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latins et payens (Paris, 1584).

(Right): The Fallen Angels, detail from the High Altar of St Peter’s in Hamburg, by Master Bertram of Mindem (c. 1379 – 1383).

Christian apologists of the second century put much effort in setting the cultural history of man within this degenerative framework, rephrasing ancient theories on the history of civilization and the inventions of arts and culture in terms of idolatry. Two fundamental themes could be put to work in this context: euhemerism, which related the gods of ancient mythology to past kings, or to divinized discoverers of things useful to man; and Enochic demonology, as preserved in the Enochic corpus of Second Temple Judaism, which traced the origins of arts and culture to the teachings of fallen angels (the “sons of God” mentioned in Genesis 6:4). This promethean mythology expounded how mankind had acquired certain knowledge by the intermediary of semi-divine powers cast out of the heavens, after they had indulged in sexual intercourse with human females — an unnatural trade that was decisive in the upsurge of evil in the world, and notably, of the existence of demons and wicked spirits.

Early Christian authors thus explained how the demonic offspring of the fallen angels had contributed to the establishment of false religions, turning, wrote Tertullian, “all elements, everything belonging to the world, everything that the heaven, the sea and the earth contain, for idolatrous purposes, so that they (the demons) would be hallowed, instead of God” (Tertullian, De Idololatria 4.2). Statues and images, “idols”, when they appeared, only gave their name to this foundational human sin by which, to the delight of the demons, mankind worships everything created but “the Creator of everything Himself.” In every way they can, the filthy demons divert mankind from the true worship of God, inventing rites that although they resemble the true religion, are but counterfeits, imitations: “idolatry”.

It was also through the workings of the demons that the great men of the past came to be considered as gods, thus contributing the establishment of false religions. Lacking a material body, the demons find refuge in the images and statues erected in memory of the dead, pronouncing oracles, and claiming to be worshipped with prayers and sacrifices. The Pagan gods, wrote Augustine, have a body and a soul: the body is the idol, but its soul is the demon (Augustine, De Civitate Dei 8.26).

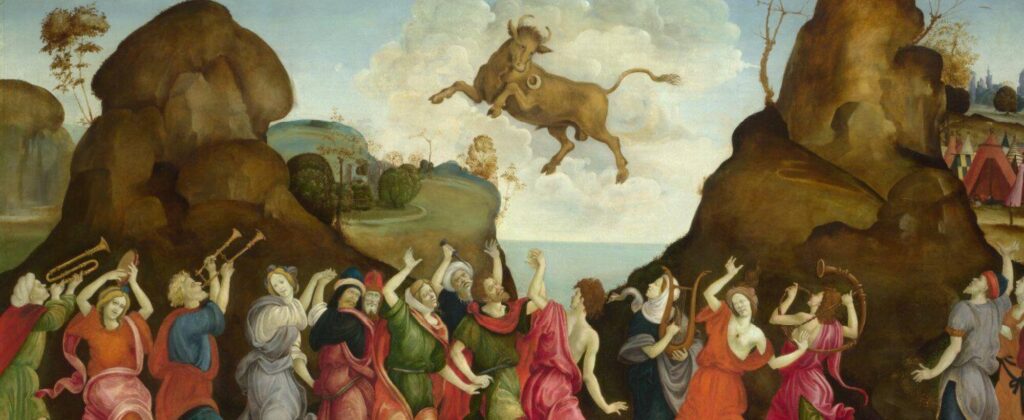

The worship of the Golden Calf in the form of an Apis Bull. Filippino Lippi or follower, Florence, c. 1500. London National Gallery, inv. 4904.

The myth of the fallen angels and of their demonic offspring thus became a central element in the Christian discourse of idolatry. It is, however, noteworthy that the same narrative was given a very different significance in early rabbinic sources.

Rabbinic midrashim strongly oppose the angelic interpretation of the “sons of God” mentioned in Genesis 6:4. In fact, the early rabbis traced the origins of idolatry to even earlier times in the primeval history of man, and tend to refuse attributing its origins — and, for that matter, the origins of evil in general — to anything other than mankind itself. Thus, they related the origins of “inappropriate worship” to the generation of Enosh, the second generation after Adam and Eve, when “people began to invoke the name of the Lord” (Genesis 4:26). The verse allowed a rather positive interpretation of Enosh as the founder of religion in Second Temple Jewish — and later early-Christian — sources. But for the rabbis, it meant that the generation of Enosh was the first to profane the name of the Lord, and to worship idols.

By contrast, Christian authors suggested the exact contrary, namely that Enosh was the first man to witness piety towards god and that the verse thus pertains to the origins of religion rather than idolatry. In his Hebrew Questions on Genesis, Saint Jerome remarked that while Christians admit that in the days of Enosh the name of the Lord was first invoked, the Jews, for their part, claim that this is when the first idols were made.

Eduard Brerewood, Enquiries Touching the Diversity of Languages and Religions (London, 1614).

Enosh thus appears as the point in history to which Christian exegetes trace the origins of religion, while the Jewish sages view it as marking the beginnings of idolatry. Obviously, these conflicting readings shed light on the ways the entangled Jewish and Christian normative traditions eventually adopted clearly distinct representations of the human condition, and of the role of man in human history. Comparing these Jewish and Christian mythologies of idolatry reveals the tension between two readings of the religious history of mankind, one theocentric, and the other one anthropocentric, considering “idolatry” as either the product of supernatural and external forces (i.e., demons) or the product of human attitudes and behaviors themselves.

The demonological pattern introduced by the Church fathers in the narrative of man’s religious history lastingly informed the Christian representation of other religions. It became almost ubiquitous in the sixteenth century, when discussing the idolatries (read “religions”) encountered by European explorers in the Americas, in India, China, or Japan. In his Enquiries Touching the Diversity of Languages and Religions (1614), the English scholar Edward Brerewood noted with astonishment that idolatry seemed to outnumber all other religions in terms of demography.

Eventually, however, “idolatry” gradually escaped the realm of transcendent powers, and was transferred to the realm of man, of human experiences and emotions. The rediscovery of the Jewish anthropocentric perspective in the early modern period, notably through the works of the medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, played an invaluable role in this paradigm shift.

(Left): Detail of a bronze statue (1964) of the Jewish Philosopher Moses ben Maimon, aka Maimonoides (1135 – 1204 CE), in Cordoba Spain. Wikimedia Commons / David Baron (CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED)

(Right): R. Moses Maimonides, De Idololatria Liber, edition and translation by Dionysos Vossius (Amsterdam, 1642).

Maimonides explained how in the days of Enosh, mankind started paying homage to the stars and celestial bodies, believing that by honoring God’s servant they were also honoring God himself. He then described how humans had gradually descended into ever more foolish forms of idolatry. False prophets arose, establishing a given star as an object of worship. Soon enough, images of these sham divinities were set up and multiplied. Idolatry became common, and the knowledge of God was blurred in the minds of most men until the days of Abraham, who was the first to openly proclaim that there is but one God who “guides the celestial sphere and created everything” (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Laws Concerning Idolatry 1). One of the main objectives of the Mosaic law, Maimonides explained, was precisely to put an end to idolatry, and correct mankind’s natural inclination to disobey God and succumb to religious impiety, and eventually moral disorder and social violence. He further sought to show how even the most obscure biblical commandment was in fact conceived by God as an antidote to the erroneous beliefs of the idolaters, as he pieced them together through a careful reading of the textual evidence found in the books of the ancient Sabians, the people in whose midst Abraham had been raised. To understand the Law, claimed Maimonides, one had to understand human nature, including man’s propension to idolatry. This also meant studying the sources available to him and provide an anthropological account of ancient religion.

Enlightenment scholars of religion followed suit. The origins and nature of idolatry thus became an essential question, soon addressed in more general terms: when and why did humans start worshipping gods, and in what form?

Daniel Barbu is a Researcher tenured at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and vice-Chair of the Graduate Program in Religious Studies at Paris Sciences-et-Lettres Research University / École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris. His essay, “The Invention of Idolatry”, recently appeared in the journal History of Religions.

How to cite this article

Barbu, D. 2023. “Who Invented Idolatry?” The Ancient Near East Today 11.6. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/barbu-who-invented-idolatry/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Post a comment