Modern Wars and Ancient Governance: Archaeology and Textual Finds from First Millennium BCE Babylon

November 2022 | Vol. 10.11

By Odette Boivin

When the German architect-turned-archaeologist Robert Koldewey and his colleagues unearthed cuneiform tablets from the ruins of Babylon in the early 20th century, they probably did not suspect that it would take over a century for most of them to be studied and published. Tablets were among the finds that captured their attention most, and the excavation notebooks reveal that the team certainly spared no effort when trying to retrieve large numbers: “we dug out tunnels eastwards and southwards in order to exploit as much as possible the find of tablets. However, the yield is modest and the tunnel walls threaten to collapse…” (July 21, 1908).

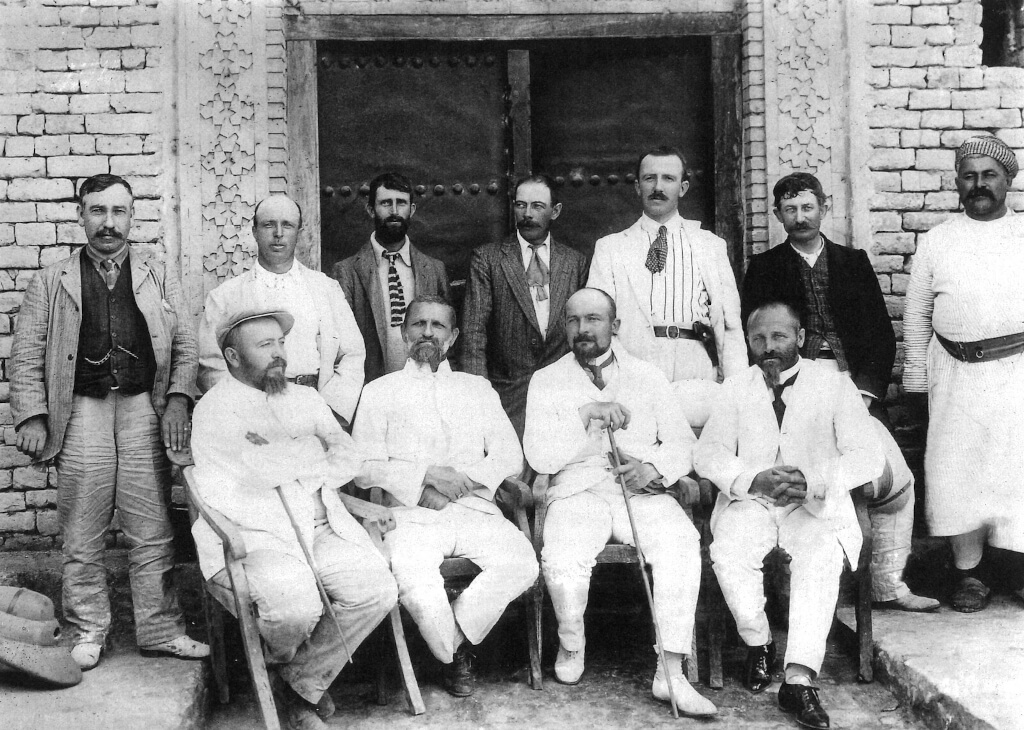

Plan of Babylon. O. Pedersén 2021. Babylon. The Great City, p. 15.

The excavations

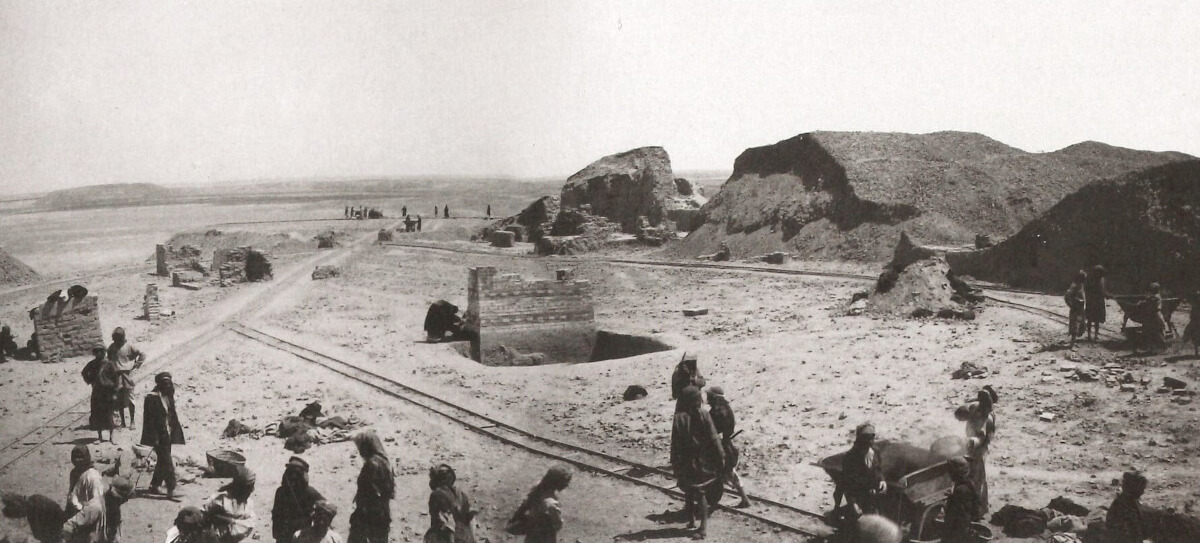

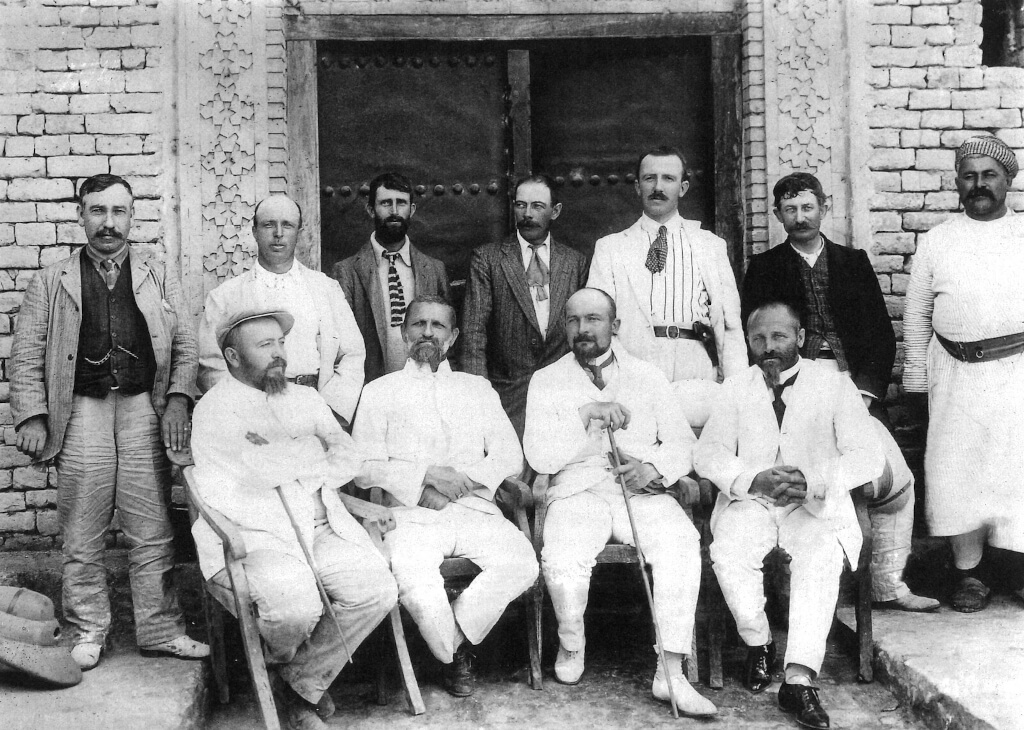

Koldewey’s excavations in Babylon, ca. 100 km south of Baghdad, ran from 1899 until 1917, when World War I put an end to the archaeological work. Over the years, Koldewey’s team included other architects with a keen interest in archaeology, like Walter Andrae, and philologists, like Franz Heinrich Weissbach. Working all year round, the team hired an average of 200 to 250 workers and excavated six days a week, rain or shine, even, as their notes recorded on August 26, 1902, when “their feet hurt from the hot sand” on a day when temperatures soared to 45 degrees Celsius after several days over 40. Unsurprisingly, the mass of earth moved, the areas and structures uncovered, and the numbers of objects retrieved are impressive.

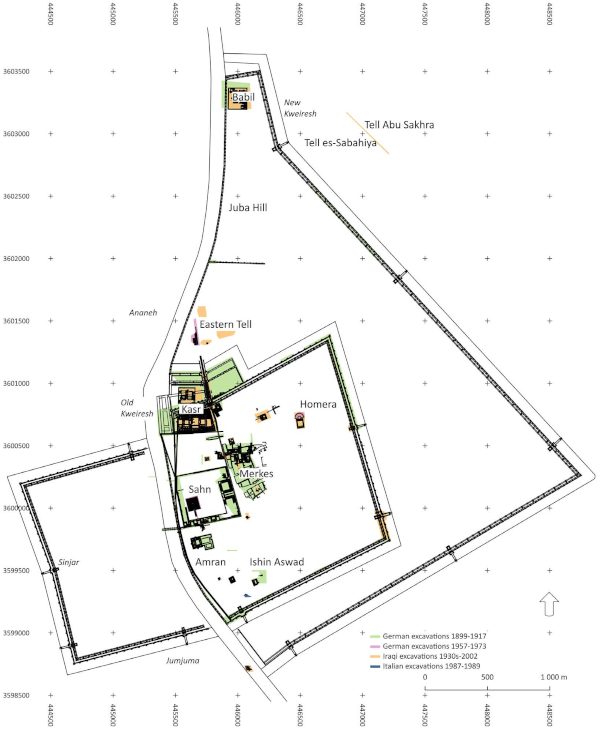

Beginning of excavations of the Ishar Gate. M. van Ess 2008. « Koldewey – Pioner systematischer Asugrabungen im Orient ». In R.-B. Wartke (ed.), Auf dem Weg nach Babylon. Mainz : Philipp von Zabern, p. 93, Fig. 2 (composite image).

Group photograph, ca. 1906. First row: F. Wetzel, R. Koldewey, O. Reuther, G. Buddensieg. From J. Marzahn 2008 « Robert Koldewey – Ein Lebensbild » in R.-B- Wartke, Auf dem Weg nach Babylon, p. 18, Fig. 8 (Vorderasiatisches Museum).

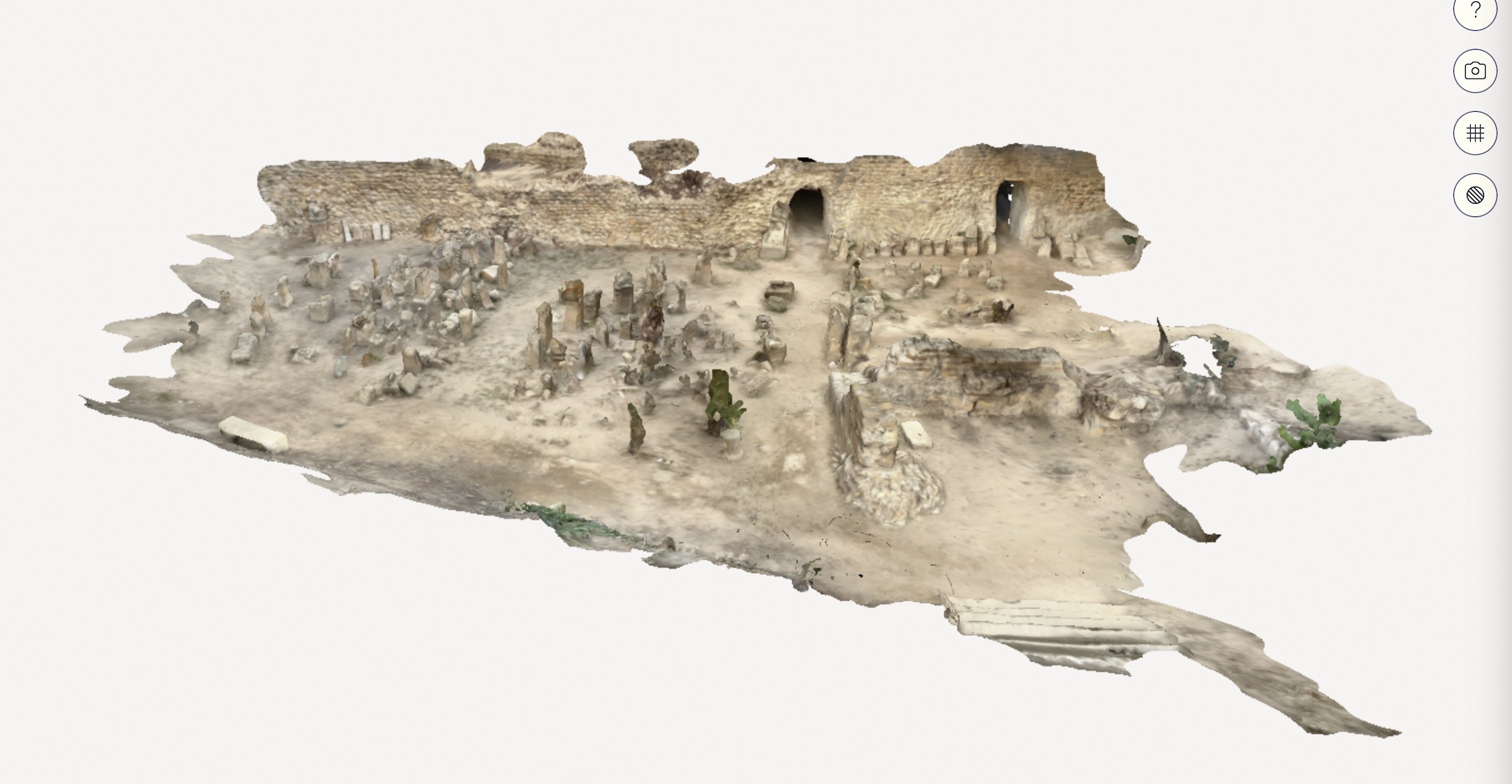

The excavations of the ancient capital extended to several mounds whose modern names are still used to designate the site’s areas. Work took place mainly within the inner city wall of Babylon, but also immediately north in the North Palace area (part of Tell Kasr), and a little upstream along the Euphrates, in the Tell Babil area (the “Summer Palace”). Large infrastructure was uncovered in the Kasr area, including the South Palace, the North Palace, the Procession Street, the Ishtar Gate, and the Ninmah temple.

Other temples were unearthed in other parts of the city: the Esagil (the temple of Marduk, the city-god of Babylon), the temple of Ninurta, the temple of Ishara, and the temple of Ishtar. The latter is located in the Merkes area, one of the most thoroughly excavated quarters. Besides the temple, several private houses were unearthed there, revealing domestic architecture as well as the layout of part of the neighborhood. The archaeologists were able to reach second millennium layers, down to the Old Babylonian period.

The high ground water table posed a difficulty, especially when compounded by abundant rain, as reflected in a notebook entry from January 27, 1908, pertaining to excavations in the Merkes area: “In order to exploit further the cluster of tablets… we must first drain the ground water and rain water that accumulated underneath.” Unsurprisingly, the tablets sometimes had to be left to dry out before extensive handling, although it appears that opinions could diverge on when they were dry enough: “Dr. Weissbach fetched the lot of tablets… to work on them. However, because Mr. Andrae has stressed several times that they are still moist, describing them as not suited to be worked on, I objected, and W. is bringing them back into the library” (February 1, 1903).

Indeed, in most areas primarily First Millennium levels could be excavated, often because earlier layers were below the ground water table. Following the convention used in the careful and detailed cataloguing of the tablets by leading scholar of Babylon, Olof Pedersén of Uppsala University, in his 2005 book Archive und Bibliotheken in Babylon these are here deemed “Neo-Babylonian” but they include the Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, Persian, Hellenistic levels/periods.

Photograph. Jar containing tablets. Credits : O. Pedersén 2005. Archive und Bibliotheken in Babylon. ADOG 25. Saarbrücken : Saarländische Druckerei unf Verlag. P. 203, Fig. 89.

Archival (legal, administrative, epistolary) or library (literary, religious, scientific) texts were uncovered in several areas: Merkes, Amran (including in the Esagil temple), Ishin-Aswad, Sahn, Homera, Kasr, and Babil. Some tablets were found in larger clusters, others were stray finds.

Disrupted object histories

From the moment tablets were unearthed by the excavators, their object history has been marred by a series of complications and events that delayed their publication, keeping their contents largely out of reach of the scholarly community. This has contributed to making Babylon remarkably silent as an important royal and imperial capital in Ancient Near Eastern history.

The limited availability of palace archival texts cannot be remedied. For the Neo-Babylonian layers, which were excavated, this relative scarcity is largely a result of how these archives were disposed of in antiquity. Although over 1,600 tablets or fragments were unearthed by the excavators in the general area of the palaces, most of them belong to the archive of city and province governors or to the Ninmah temple. Earlier layers were not excavated (only three texts of Middle Babylonian date were retrieved from the South Palace). But numerous texts were found in other parts of the city during Koldewey’s excavations—from houses, temples or rubble pits—, or were acquired from local people. Pedersén established the number of tablets or tablet fragments unearthed, for all periods, at 5,225, the vast majority of which are of Neo-Babylonian date.

However, the task of making their contents available had only barely begun when excavations stopped abruptly in 1917. Most objects that had not already been shipped to Istanbul or Berlin, based on a first division of finds with the Ottoman Empire, remained in the excavation house, which was left unguarded. In the 1920s, when the main division of finds took place, this time with the newly founded state of Iraq, a number of these artefacts had vanished.

The Babylon Project estimates the total number of objects unearthed at ca. 77,800. Of these, an estimated 30,000, are in Berlin, including a very large number of small fragments, for instance of the Ishtar Gate, and ca. 2,300 tablets or tablet fragments. Most texts went presumably to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad and ca. 130 to Istanbul. A number of tablets found their way into other collections, probably as the result of gifts or looting from the excavation house.

In Berlin, work on the collection was severely disrupted by World War II, after which the damaged museums had to be rebuilt, the finds inventoried and their preservation state verified. In Baghdad, the Iraq Museum was looted in 2003 during the Iraq War. While tablets from the Koldewey excavations in Babylon are reported to be extant, their number is at present unknown.

Towards closing the gap

The ERC-funded project “Governance in Babylon: Negotiating the Rule of Three Empires” (GoviB; 2021–2026), under the lead of Kristin Kleber (University of Münster), is now taking a step towards closing a significant portion of this gap of information about and from Babylon. Over a century after Koldewey’s excavations, it is making the contents of ca. 700 archival texts from Babylon available to the scholarly community and more broadly to the general public.

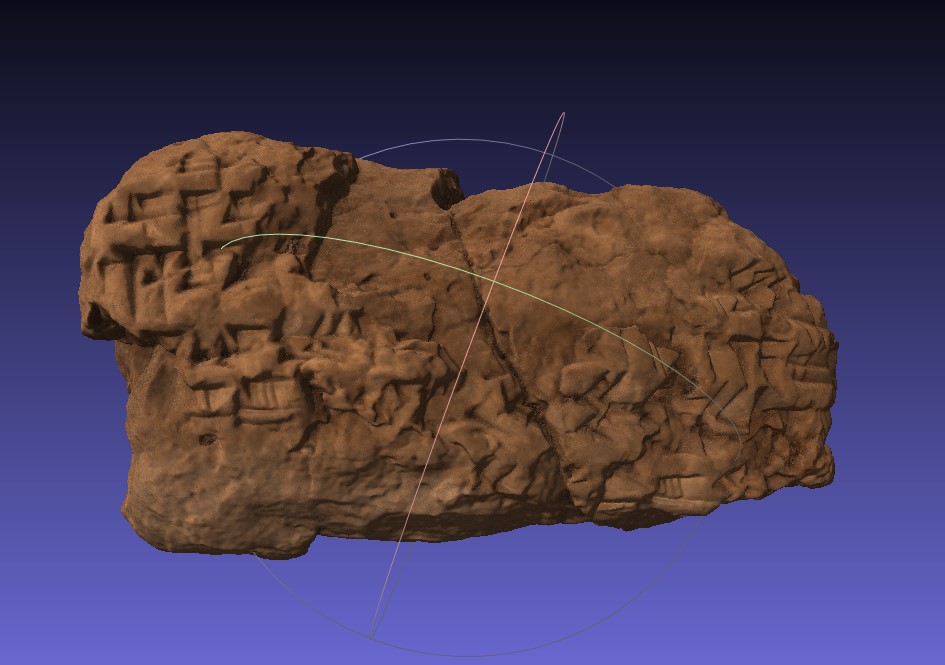

3-D Scan of a cuneiform tablet.

The project’s aim is twofold. The objective of the first phase is to publish the editio princeps of the available archival texts from “Neo-Babylonian” layers of private houses and temples. A little over 400 of these approximately 700 tablets have an archaeological context. This is a rare privilege in Neo-Babylonian studies since most finds from that period come from the antiquities market. An extended archival approach will be applied; whenever possible, a text will be considered within both its archival and archaeological contexts, including other associated object finds. In addition to traditional philological study, the tablets are photographed using RTI technology (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) and scanned in 3D.

GoviB is greatly indebted to two projects that essentially made it possible for the team to begin working with the materials themselves from the start. The first is the structuring work of Pedersén who catalogued the tablets, grouping them in archives, libraries, or text assemblages based on archaeological context. This was followed by the Babylon Project (2016–2021), which systematized cataloguing of other objects, including associated object histories, and digitized archaeological documentation.

GoviB collaborates with Pedersén, who is editing the tablets from the South Palace, as well as with Daniel Schwemer (University of Würzburg) and Nils Heeßel (University of Marburg), who are publishing the texts housed in Istanbul (in the context of the project “Die Keilschrifttexte der Babylon-Sammlung der Archäologischen Museen Istanbul”).

The second phase of the GoviB project aims at exploiting the new textual evidence in order to reassess the role of empires in the long-term cultural transformation of the Near East by applying the conceptual framework of governance studies. The texts were written by members of the city elites of Babylon, socially close to main institutions of power across two regime changes, from Neo-Assyrian domination to Babylon self-rule in 626 BCE, and to integration into the Persian empire in 539 BCE. Hence, they offer a privileged source for a historical study of governance in Babylon from ca. 690 BCE until the aftermath of the Babylonian revolt against Xerxes I in 484 BCE. This evidence presents also great potential for challenging static, top-down ideas of despotic imperial rule.

Koldewey’s excavations revealed a significant portion of the city plan of Neo-Babylonian Babylon, numerous large infrastructures like the Ishtar Gate and the South Palace, and they have made studies in domestic architecture and urban topography possible. Now, at long last, more textual finds are being exploited. This will continue lifting the veil on life in the Mesopotamian capital Babylon through wars and regime changes.

Odette Boivin is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Institut für Altorientalistik und Vorderasiatische Archäologie of the University of Münster.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 101001619).

Further Reading:

Pedersén, O. 2005. Archive und Bibliotheken in Babylon. Die Tontafeln der Grabung Robert Koldeweys 1899-1917. Saarländische Druckerei und Verlag.

Pedersén, O. 2021. Babylon, The Great City. Zaphon.

How to cite this article

Boivin, O. 2022. “Modern Wars and Ancient Governance: Archaeology and Textual Finds from First Millennium BCE Babylon.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.11. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/boivin-modern-wars-ancient-governance/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Post a comment