The Exceptional Career of a Mesopotamian Ruler without a Crown: Kudur-Mabuk and the Kingship of Larsa

January 2022 | Vol. 10.1

By Baptiste Fiette

Where did Mesopotamian kings come from?

In the second third of the 19th century BCE, the kingdom of Larsa in southern Mesopotamia went through a politically tumultuous phase. During this period, a complex individual emerges: Kudur-Mabuk, a man of Elamite origin, whose political career can be traced back to the reign of Sin-iddinam (1849–1843 BCE). But only a decade later, he would witness his sons Warad-Sin (1834–1823 BCE) and later Rim-Sin (1822–1763 BCE) becoming kings.

Who was Kudur-Mabuk and what is the evidence for his career? How did an Elamite establish a political career in southern Mesopotamia and set the stage for his sons to become kings?

During the time of the last kings of the Nur-Adad dynasty, Kudur-Mabuk was a high official of the kingdom of Larsa, as it is shown by three administrative documents related to the royal court. They mention Kudur-Mabuk with female and male musicians, “the house of women,” or Ṣilli-Adad, probably the future king of Larsa in 1835 BCE. In one, dated to the last year of king Sin-iddinam (1843 BCE), Kudur-Mabuk appears alongside female mourners probably related to the funeral ceremony of Sin-iddinam. Thus Kudur-Mabuk was already a prominent figure of the kingdom, even before the accession of his son Warad-Sin in 1834 BCE. During this time, Kudur-Mabuk seems to have exercised some functions at Maškan-šapir, the capital of the land of Emutbal in the northern part of the kingdom.

Clay cone inscription in Akkadian by ‘Kudur-Mabuk, father of the Emutbal land, son of Šimti-šilhak”, ca. 1825 BCE, Musée du Louvre, Paris (AO 6445 = RIME 4: 267–268, text no. 2) © 2007 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux

An important element of Kudur-Mabuk’s identity is his Elamite origins. Kudur-Mabuk bore an Elamite name, which means “(The god) Mabuk is a protector.” Since the names of his father Šimti-šilhak and his daughter Manzi-wartaš are also Elamite, it is probable that Kudur-Mabuk’s family hailed from Elam. The earlier history of this family remains unknown. However, it is interesting to observe that a foreigner was able to become a high dignitary of a Mesopotamian kingdom, and even to integrate its royal court.

The ascension of Kudur-Mabuk should be explained first with regard to the political troubles that disturbed the kingdom of Larsa at the end of the Nur-Adad dynasty. In 1843 BCE, Sin-iddinam died because of a plague, which has afflicted the people of Larsa whereas the city was surrounded by enemies, according to two letter-prayers written by this king to the god Šamaš and the goddess Nin-Isina. Sin-iribam, his successor, was not his son but the son of Ga’eš-rabi. Sin-iribam reigned only two years (1842–1841 BCE), his son Sin-iqišam five years (1840–1836 BCE) and Ṣilli-Adad only nine or ten months in 1835 BCE, before he lost the kingship. According to the last year-name of Sin-iqišam, several enemies also attacked the kingdom of Larsa at this time.

Stone foundation tablet in Sumerian dealing with the construction of the temple of the goddess Nanaya by ‘Kudur-Mabuk, father of the Emutbal land, son of Šimti-šilhak, and Rim-Sin his son’, ca. 1820 BCE, Musée du Louvre, Paris (AO 4412 = RIME 4: 274–275, text no. 3). © 2012 Musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault

Based on this evidence, the seizure of power by Kudur-Mabuk could be reconstructed. While the kingdom of Larsa was attacked and royal power became unstable, Kudur-Mabuk held his position at Maškan-šapir. He then restored the territory and kingship of Larsa, starting the reconquest from the northern part of the kingdom. Some later evidence may confirm this hypothesis: Maškan-šapir during the reign of Rim-Sin (1822–1763 BCE) became the second capital of the kingdom of Larsa. At the time of the Babylon’s domination (1762–1738 BCE) after Hammu-rabi’s conquest of the kingdom of Larsa, Maškan-šapir was a major administrative center of the Babylonian province called Emutbal.

The kingdom of Larsa thus suffered a serious political crisis before Warad-Sin became king in 1834 BCE. An inscription of Kudur-Mabuk mentions an attack against the temple of Šamaš, in the heart of Larsa, which might have provoked the fall of Ṣilli-Adad. Other attacks against the kingdom and its capital marked the very beginning of Warad-Sin’s reign. Kudur-Mabuk repelled some of them, fighting against troops of Kazallu and the land of Mutiabal or against a rebel from Maškan-šapir named Ṣilli-Ištar.

Kudur-Mabuk did not accede himself to the throne, even though he was still alive when his sons were crowned. His death probably occurred during the fourth year of Rim-Sin. But what was Kudur-Mabuk’s political status during the reigns of his sons?

Kudur-Mabuk was very involved in the commemorative inscriptions dating to the reign of Warad-Sin and the beginning of Rim-Sin’s reign. He was associated with his sons for the exercise of kingship, as abi Amurrim “Amorite chief” during Warad-Sin’s years 1–6, and then as abi Emutbal “chief of the land of Emutbal” during Warad-Sin’s years 7–12 and Rim-Sin’s years 1–4. Moreover, his own daughter En-ane-du (possibly Manzi-wartaš) was appointed as enum-priestess of the Moon-god Nanna at Ur, in 1829 BCE. This had been a royal privilege since the 3rd millennium. In view of his political influence, we can assume that Kudur-Mabuk himself enthroned Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin.

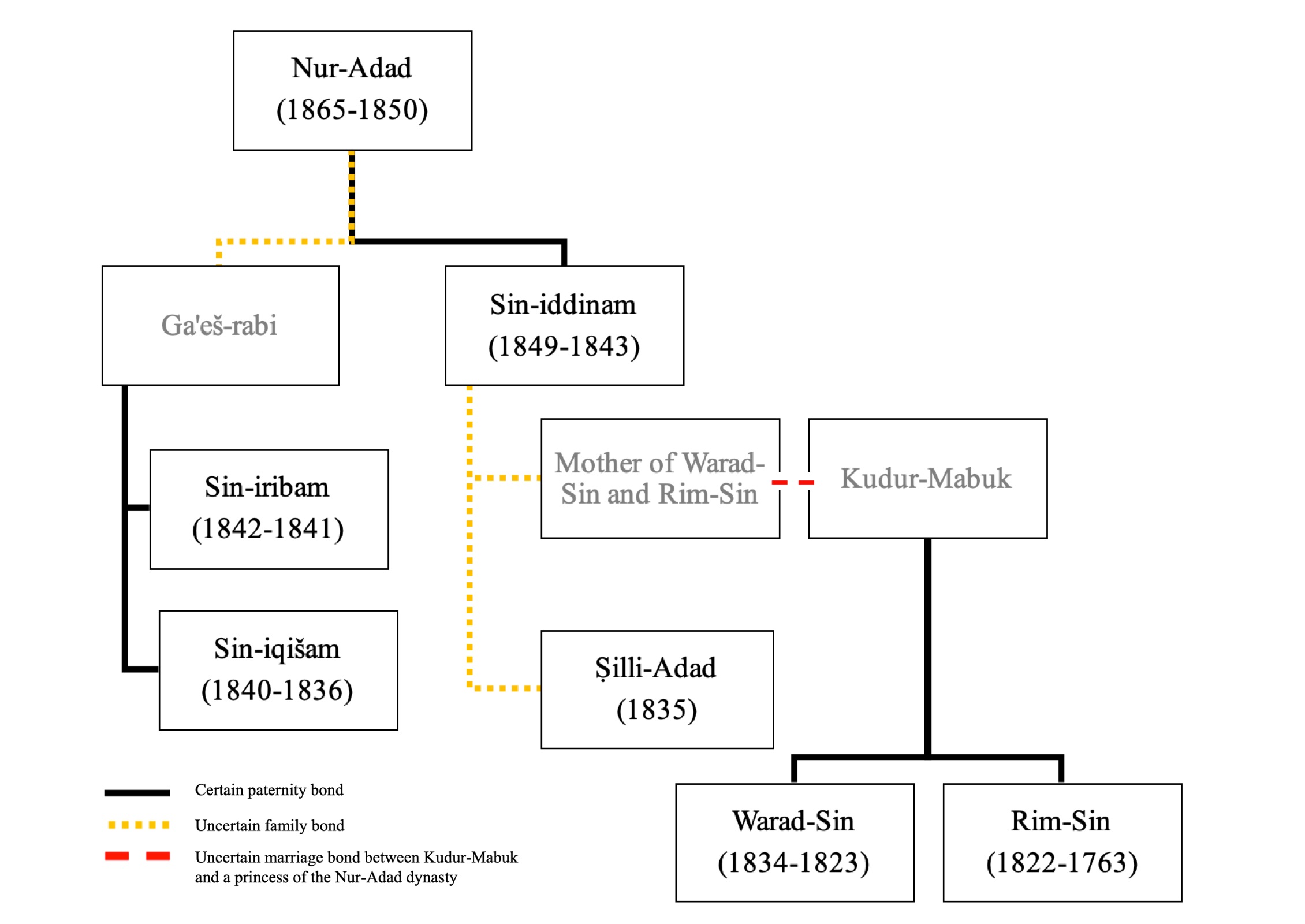

Nur-Adad and Kudur-Mabuk dynasties: hypothetical familial ties. Photo courtesy of the author.

But why did Kudur-Mabuk deny himself the opportunity to accede to the throne of Larsa? P. Steinkeller has suggested an attractive hypothesis. Observing that Rim-Sin commemorated several offerings of statues depicting Warad-Sin, Kudur-Mabuk and Sin-iddinam during the first years of his reign, he proposed that these corresponded to a family cult. He concluded that Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin were the grandsons of Sin-iddinam, offsprings of a marriage between Kudur-Mabuk and a princess of the Nur-Adad dynasty. In this way, their legitimacy would have been based on blood ties.

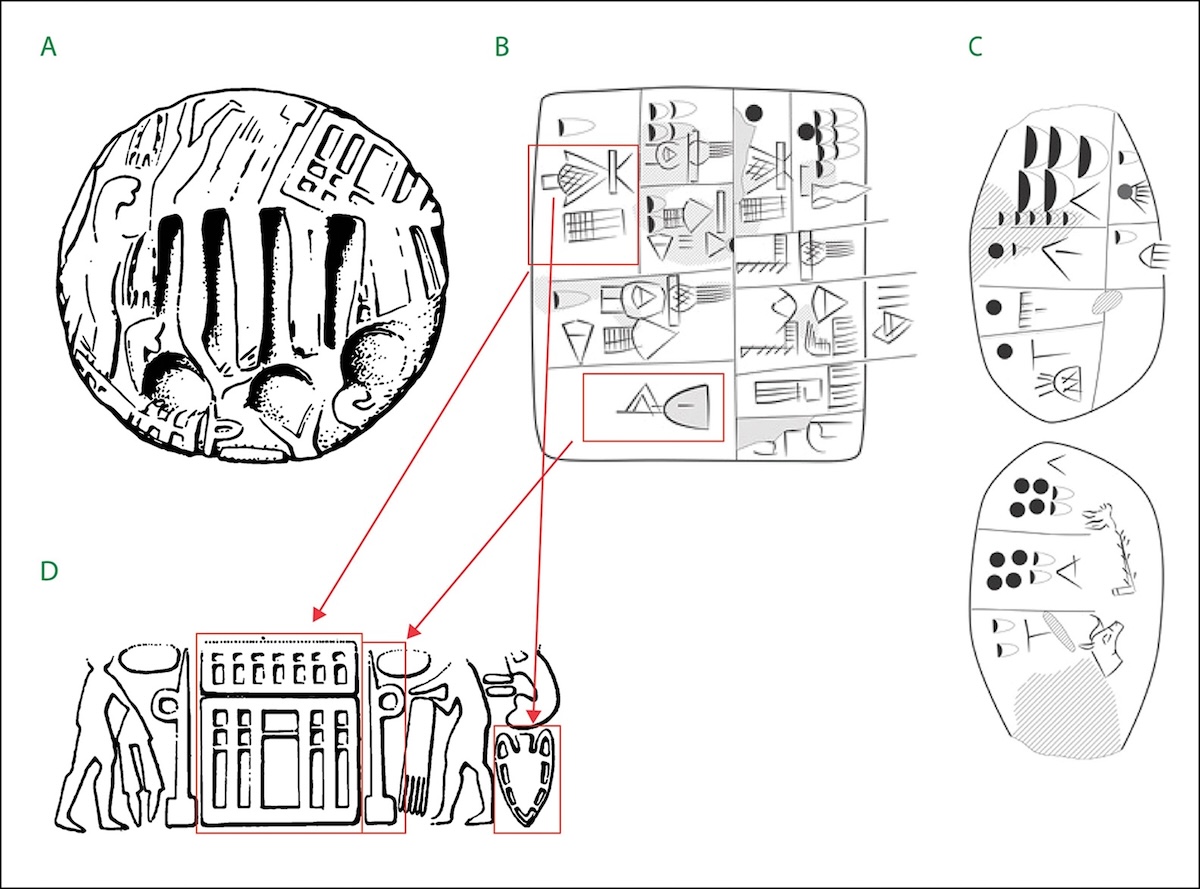

Kudur-Mabuk therefore had some royal prerogatives: the production of commemorative inscriptions on his own behalf, the capacity to appoint his own daughter as enum-priestess of Nanna, and his depiction as a victorious king setting his foot on Ṣilli-Ištar, the rebel from Maškan-šapir, which recalls well-known royal representations showing kings trampling on their enemies.

The passage of one undated text does mention Kudur-Mabuk among kings. It concerns a sacrifice dedicated to the lama-spirits of dx-x-BU, Šulgi (king of Ur, 2094–2047 BCE), Sin-iddinam, Sin-iribam, Sin-iqišam, Kudur-Mabuk and Warad-Sin. It was probably written during the reign of Rim-Sin.

Moreover, the title LUGAL, “king” is attested for Kudur-Mabuk in the copy of the inscription on the victory stele depicting Kudur-Mabuk as victorious against Ṣilli-Ištar. But it was a later attribution, obviously a confusion about his political status linked to his preeminent position in the kingdom. Despite Kudur-Mabuk’s preeminent political status, the scribal tradition of Larsa did not consider him as a king: his name is neither mentioned in the Larsa King List, nor in chronological lists of year-name formulae. Indeed, no year-name of Kudur-Mabuk was ever found.

Stela of Mardin’ representing Samsi-Addu, king of Ekallatum, trampling and killing an enemy, ca. 1790 BCE, Musée du Louvre, Paris (AO 2776). © 2016 Musée du Louvre / Thierry Ollivier

Kudur-Mabuk was a pillar of the kingdom of Larsa. He seized power thanks to his emerging strength, without reigning as a king but acting as a father in many ways: father of kings Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin as well as paternal figure of the Emutbal and its population, as reflected in his titles abi Amurrim and abi Emutbal. His identity is exceptional throughout Mesopotamian royal history and explains why Kudur-Mabuk could have been later considered as a king, or mentioned among kings.

Observing his career in term of ethnicity, one can assume that his Elamite origin had played no part. Kudur-Mabuk may have been an ambitious individual, but also a faithful servant of the kingdom, probably already integrated in the royal family. The ascension of his own family was a matter of circumstances, during a time of political trouble.

Baptiste Fiette is a member of the UMR 7192: “Proche-Orient–Caucase: langues, archéologie, cultures” (Collège de France, Paris).

Further Reading:

Charpin, D. 2018. “En marge d’EcritUr, 1 : un temple funéraire pour la famille royale de Larsa?” Notes Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2018, no 1.

Charpin, D. 2020. “Enanedu et les prêtresses-enum du dieu Nanna à Ur à l’époque paléo-babylonienne”. In D. Charpin, M. Béranger, B. Fiette & A. Jacquet, Nouvelles recherches sur les archives d’Ur d’époque paléo-babylonienne. Mémoires de N.A.B.U. 22. Paris: Société pour l’Étude du Proche-Orient ancien, pp. 187-210.

Fiette, B. 2020. “‘King’ Kudur-Mabuk. A Study on the Identity of a Mesopotamian Ruler Without a Crown”. Die Welt des Orients 50/2, pp. 275-294.

Fitzgerald, M. A. 2005. “The ethnic and political identity of the Kudur-mabuk dynasty.” CRRAI 48. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 101-110.

Peterson, Jeremiah. 2017. “A Fragmentary Attestation of the lama of King Ur-Ninurta of Isin.” Notes Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2017, no 61.

Steinkeller, P. 2004. “A History of Mashkan-shapir and Its Role in the Kingdom of Larsa.” In E. C. Stone & P. Zimansky (eds.), The Anatomy of a Mesopotamian City. Survey and Soundings at Mashkan-shapir. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 26-42.

How to cite this article

Fiette, B. 2022. “The Exceptional Career of a Mesopotamian Ruler without a Crown: Kudur-Mabuk and the Kingship of Larsa.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.1. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/fiette-king-kudur-mabuk/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Post a comment