Archaeology of the Silk Road: What Lies Ahead?

November 2023 | Vol. 11.11

By Kate Franklin

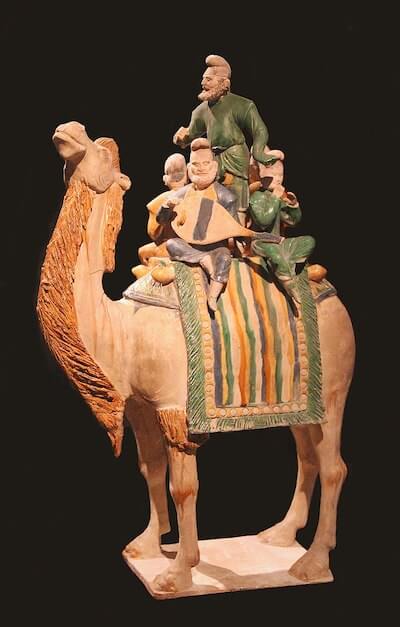

The idea of the Silk Road seems to be everywhere: bestselling books, museum exhibits, conferences, tours, travelogues, and geopolitical strategies deploy the term. The term evokes familiar-strange imagery associated with ancient travel and trade in Eurasia: a camel caravan walking atop a wind-blown sand dune; a crowded bazaar buzzing with a hundred languages and thick with the scent of spices; elegant architecture rising from the desert dust, ringing with echoes of now-lost societies; sheaves of documents inked in strange scripts, ruffled by cool cave winds. But what are the Silk Roads — and more important for archaeologists — what were the Silk Roads, and how do we study them?

The caravan of Marco Polo as depicted in the “Catalan Atlas” by Cresques Abraham, 1370–1380 CE. Bibliothèque nationale de France (Public Domain).

A Global Past in Eurasia

At heart, the idea of the Silk Road is a story about human interactions at global scales and about the knitting together of a “world” across Eurasia through travel and trade. Most scholars who work on the Silk Roads focus on a few key periods of interactions between “east” and “west”: between Han China and the Roman and Persian Empires from the first centuries BCE to the first centuries CE; between the Byzantine Empire, the Islamic caliphates and the Tang and Song dynasties in the 6th–10th centuries CE; or the mobility made possible by the “pax Mongolica” of the thirteenth-fourteenth centuries CE. During these periods, cultures across Eurasia were galvanized by the circulation of goods, technologies, and ideas, and transformed by the mobility of people: merchants like Marco Polo, travelers like Xuanzang, and pilgrims like Ibn Battuta, but also conquering armies, displaced exiles, and traded slaves. From an archaeological perspective, we can see the “encounters” of this long period in material traces: in the intriguing mix of Grecian and Asian techniques in “Greco-Buddhist” art; in the popularity of Chinese porcelain in the cities of the Islamic world; in the mania for Indian pepper and Chinese silk in Roman cities; or in the construction of networks of infrastructure to support all that travel, including caravan hotels (caravanserais), wells, roads, and bridges.

(Left): Seated Buddha statue, displaying Mediterranean stylistic influence, Pakistan. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.593.1 (Public Domain).

(Right): Sasanian Persian silk fragment, depicting variants of Chinese dragons. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.147 (Public Domain).

Light From the East

But significantly before anyone thought of a “Silk Road”, the germ of the idea was developed in the context of European and American orientalism, by which I mean the scholarly study of questions related to the east, or orient. The idea of a great movement westward of goods like silk, but also of “civilizational ideas” including religion, music, philosophy, and (especially) languages, is fundamental to the disciplinary conversation of orientalism, which drove so much of the scientific exploration of the 18th-20th centuries (and today). For a long time, the study of a historical east-west trade route was tied up in many scholar’s minds with the idea of the eastern origins of western civilization — that lux ex oriente idea that sparked the founding of many institutes of Oriental studies. Even Immanuel Kant in his 1795 Perpetual Peace was enchanted by the idea of camel caravans — “the ships of the desert” as he called them — bringing together different ancient societies from east and west into harmonious, cosmopolitan relationships.

Sir Marc Aurel Stein’s excavations at Lop Nor in the Tarim Basin (Ruins of Desert Cathay Volume I, Plate 124. Public Domain).

Inventing the Silk Road

That body of ideas about Eurasia then formed the basis for discussions about a historical phenomenon that from the late nineteenth century came to be called “the Silk Road”, especially following the coining of the term in German — Seidenstraße — by the geographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen in 1877. But the idea of the ancient silk roads really took fire in the imagination of the world thanks to archaeological expeditions into the heart of Central Asia, made possible by the period of competitive imperial conquests and explorations of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which are sometimes referred to as “the Great Game”. Undoubtedly the most famous silk road archaeologist of this era was the Hungarian-British Sir Marc Aurel Stein, who led four expeditions into Central Asia between 1900 and 1930. Supported by native guides, Chinese and Indian assistants, and caravans of pack camels, Aurel Stein explored the basin of the Tarim River in what is now Xinjiang, recovering marvelously desiccated remains from the dry sands of the Taklamakan desert. Published in a series of page-turner books (one of which includes a tale of unmasking a forger of antiquities which inspired Aurel Stein’s friend Rudyard Kipling to write a similar story), Stein’s expeditions generated collections of artifacts and also thousands of texts in ancient languages like Sanskrit and Sogdian, many of which were recovered from a hidden chamber in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang. These collections fanned the flames of curiosity about ancient Central Asia and routes connecting China and the West as they were exhibited in museums around the world.

New Directions on the Silk Road

In the decades following Stein and his colleagues’ work, that intense curiosity has driven a growing community of archaeologists, historians, and other researchers toward expanding, interdisciplinary research into the history of human encounter and commerce across Eurasia. As you can explore in my recent article in the Journal of Archaeological Research, archaeologists trace the movement of people, objects, and ideas across Eurasia using a myriad of techniques and approaches, from the excavation of cities, forts, and caravan infrastructure, to isotope analyses on human and animal bones, to compositional analyses on artifacts. An expanding and controversial set of approaches focuses on DNA evidence of humans, plants, and animals, tracking the transformation of genotypes through movement and encounter of populations in the past. Archaeologists who write about the Silk Road work on sites and collections scattered from Scandinavia to South Asia and are joined by colleagues working on the “maritime Silk Road” of the Indian Ocean, which complemented overland trade with equal complexity. This profusion of work on the Silk Road is tied together by a few shared questions and challenges. The first is the question of scale: at what scale can we study global interaction, and at what scale did people in the past understand their world? The second major question is that of storytelling: when we write material histories of the Silk Road, whose stories are we telling? The creative interdisciplinarity of archaeological research takes aim at the first question, as Silk Road archaeology brings specialists working at seismic, genetic, and historical time scales into conversation. The second issue may be addressed by the increasing diversity of practitioners, stakeholders, and approaches to the Silk Road, telling the story of human encounters not just from the perspective of heroic masculine travelers from “east” and “west,” but also from other experiences, and from places in between and along the “road.”

A depiction of the Virgin Mary seated on a silken carpet, 13th century CE, Noravank Monastery, Armenia (Photo by the author).

What lies ahead for archaeology of the Silk Road? Increasing interest in the idea of ancient cosmopolitan interaction in Eurasia is driven from a number of directions. Archaeological heritage of the Silk Road has been entered into the UNESCO World Heritage List; meanwhile, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has supported excavation and curation of Silk Road sites across Eurasia, from China to Xinjiang to South Asia to Africa. The idea of the Silk Road has potential to continue breaking down disciplinary boundaries between archaeologists working in different regions and to reconfigure our approaches to museum collections and assemblages. Though the Silk Road of the future might not resemble Richthofen’s map or Marco Polo’s story, it may still move us towards new encounters with the past and with each other.

Kate Franklinis Senior Lecturer in the School of Historical Studies at Birkbeck, University of London. Her recent article, “Archaeology of the Silk Road: Challenges of Scale and Storytelling” was recently published in the Journal of Archaeological Research.

How to cite this article

Franklin, K. 2023. “Archaeology of the Silk Road: What Lies Ahead?” The Ancient Near East Today 11.11. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/franklin-silk-road/.

Want to learn more?

Putting Carthaginian Stelae Back Into Context: The ASOR Punic Project Digital Initiative

Cyprus and Ugarit: A Tale of Two Late Bronze Age Mercantile Polities

Post a comment