Scarabs in Pre-Roman Italy

april 2022 | Vol. 10.4

By Enrico Giovanelli

Scarabs are quintessential Egyptian objects. Made from a variety of materials, scarabs depict the dung beetle with folded wings and are associated with Khepri, the god of the morning sun. They appear first in Egypt in the third millennium BCE and then become widely distributed throughout the Near East and Aegean. Examples are found as far east as Kuwait and Iran.

But Egyptian and Egyptianizing objects are also one of the hallmarks of the contacts between Egypt and the Italian peninsula during the first millennium BCE, the Iron Age and the Orientalizing period. Among these items, scarabs represent the main type of findings. But what are they really and what do they signify?

The most ancient imports to Italy are four scarabs found in the Early Iron Age necropolis of Torre Galli, Calabria. They were found in female burials dating to the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 9th century BCE. After that, scarabs have mainly been documented on the Mid-Tyrrhenian coast (Etruria, Latium and Campania), in burials dating to the first half of the 8th century BCE.

Scarab from Tarquinii. Photo courtesy of the author.

At Tarquinii a scarab from a Villanovan “pozzetto” tomb is especially intriguing. The burial dates to the end of the 9th or the beginning of the 8th century BCE. But the cartouche includes the name Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV, a pharaoh of the 13th dynasty, dating to the 19th century BCE.To judge from the name, the scarab is much older than its final context and suggests it was a sort of heirloom. But this interpretation is improbable. It is more likely that this artifact is a reproduction of a second millennium cartouche on a much later piece. In fact, during the first centuries of the Third Intermediate Period (the first four centuries of the first millennium BCE), many Egyptian workshops were still producing quite good steatite and faience scarabs, only copying earlier examples. The first Egyptian imports in Italy have been attributed to Levantine traders, usually identified as Cypriots, and slightly later to Phoenicians. These items precede (or at least minimally overlap) with the earliest Greek Geometric pottery findings in Italy, which cannot be dated to before 775/750 BCE.

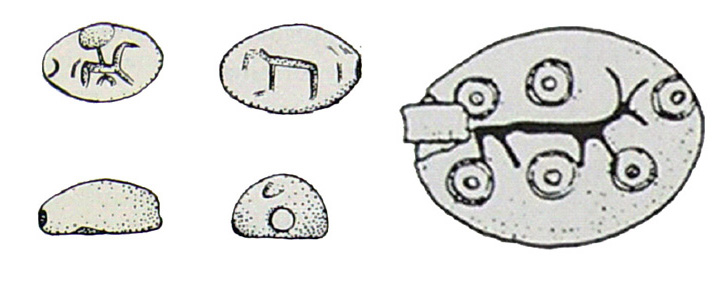

The particular appreciation given to Egyptian and Egyptianizing objects is also testified by local imitations. For example, at Veii and Vetulonia during the same period amber scarabs and scaraboids were being created by indigenous workshops.

At the end of the 8th century BCE, the number of the scarabs increases in Italy, in particular due to rising production of the so called “Perachora-Lindos” types – which are attributed to workshops not in Egypt, but on the Island of Rhodes. These quickly became the main types documented in Italy. This shift is particularly well represented at Pithekoussai (Ischia) and at Pontecagnano and in nearby (Southern Campania). Etruria (especially the southern cities like Veii, Caere, Tarquinii and Vulci) and Capua (Northern Campania) seemed to remain more linked to networks reciving actual imports from Egypt.

Amber scarab from Veii. Photo courtesy of the author.

But the final part of the Orientalizing period (630-580 BCE) showed a drastic drop in the presence of scarabs in the burials. There are only two large groups of scarabs, from the votive depots of the temples of Portonaccio (Veii) and Satricum. As in Greece, both of the sacred areas were dedicated to healing cults related to goddesses. Even though at Portonaccio the main god was Aplu, during the last decades of the 7th century BCE and the first part of the 6th century BCE a type of Minerva – with particular aspects linked to health and divination – was also venerated. At Sacricum, Mater Matuta – a local diety eventually identified with the Roman dawn goddess Aurora – remained the main figure.

This change has been usually attributed to the development and consolidation of the Latin city and its religous-political system, meaning that goods such as scarabs shifted from the funerary and private realm to the sacred and public dimension. This phenomenon was particularly stimulated in Southern Etruria and Ancient Latium by the progressive imposition of sumptuary laws during the Archaic Period. The scarabs from Veii and Satricum are mainly of Naucratite origin. The western Nile Delta city of Naucratis had superseded Rhodes as a site for the production of trade items by end of the 7th century BCE and achieved a high level of commercial success.

In this last phase of the Orientalizing period only a few scarabs reached the Adriatic coast. These were still mainly Naucratite products or other late Egyptianizing imitations. As on the Tyrrhenian coast, they were found mainly in female aristocratic burials. Their later arrival could be explained by the general trend on the Mid-Adriatic coast where consolidated commercial routes with the Aegean and Levant only developed during this late phase.

Like other Egyptian and Egyptianizing objects, scarabs were considered firstly as amulets but the ideas and values linked to them were not only of Egyptian derivation. These concepts were filtered by Levantine peoples, during a period of intense trade and cultural interaction.

Amber scaraboid from Vetulonia. Photo courtesy of the author.

One example of this confluence of various ideas are the types of mounts in which scarabs could be inserted, namely sickle or elliptic pendants. These types are of Levantine origin and derive from second millennium BCE pendants documented in Mesopotamia. They resemble the crescent moon and were considered as amulets even without the insertion of any other object. They were associated with scarabs in those areas where contact between different people was frequent such as Al-Mina, Cyprus, the Dodecanese and Pithekoussai itself.

The fusion of Egyptian scarabs and Levantine pendants communicated complex messages to Italian consumers. The details are obscure, but the presence of these artifacts speaks to the intensity of trade and thought that connected the Central and Eastern Mediterranean during the first millennium BCE.

Enrico Giovanelli is a post-doctoral research fellow at the Department of Cultural Heritage and Environment, Università degli Studi di Milano.

How to cite this article

Giovanelli, E. 2022. “Scarabs in Pre-Roman Italy.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.4. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/giovanelli-scarabs-italy/.

Want to learn more?

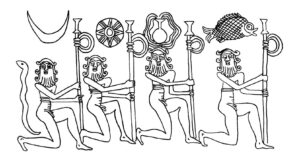

Ceremonial Standards in the Visual Culture of Early Mesopotamia

Post a comment