Portraits of People and Society From Palmyra

june 2022 | Vol. 10.6

By Maura Heyn

The funerary portraiture from the city of Palmyra, in the eastern Roman Empire, is a rich and heterogenous display of identity dating to the first three centuries CE.

Palmyra, positioned on an oasis in the Syrian steppe, flourished because of the role its inhabitants played in the caravan trade that crossed through the region. The wealth thereby accrued was used to finance the construction of temples, arches, colonnaded streets, an agora, theater, lavish houses and more in the urban core, and to erect monumental, multigenerational family tombs on the outskirts of the city. Inside these tombs, the burial niches for inhumations were sealed with limestone relief portraits.

Palmyra with the Temple of Bel. Used under CC BY-SA 3.0, credited to Bernard Gagnon

Most reliefs depicted individuals, but some Palmyrenes were displayed in pairs, or with children in their arms or standing behind their shoulders. In select tombs, lavish banquet scenes sealed off whole banks of burial niches or were paired with two to four other banquet scenes in specially built sections or prominent locations of the tomb.

Palmyrene sculpture was traded widely on the antiquities market in the late 19th and early 20th century, and there are large collections outside of Syria at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, as well as smaller collections in many museums in Europe and the United States. Scholarly knowledge of these portraits has increased exponentially in the last decade, largely due to the Palmyra Portrait project, directed by Rubina Raja of Aarhus University in Denmark, which has resulted in the creation of a forthcoming database of thousands of portraits as well as the occasion of numerous academic workshops. The funerary portraits from Palmyra have also received increased attention in recent years with the tragic destruction of the site of Palmyra, the assassination of the retired Director of Antiquities, Khaled al-Asaad, and the displacement of the local population due to the civil war in Syria and Daesh atrocities at the site.

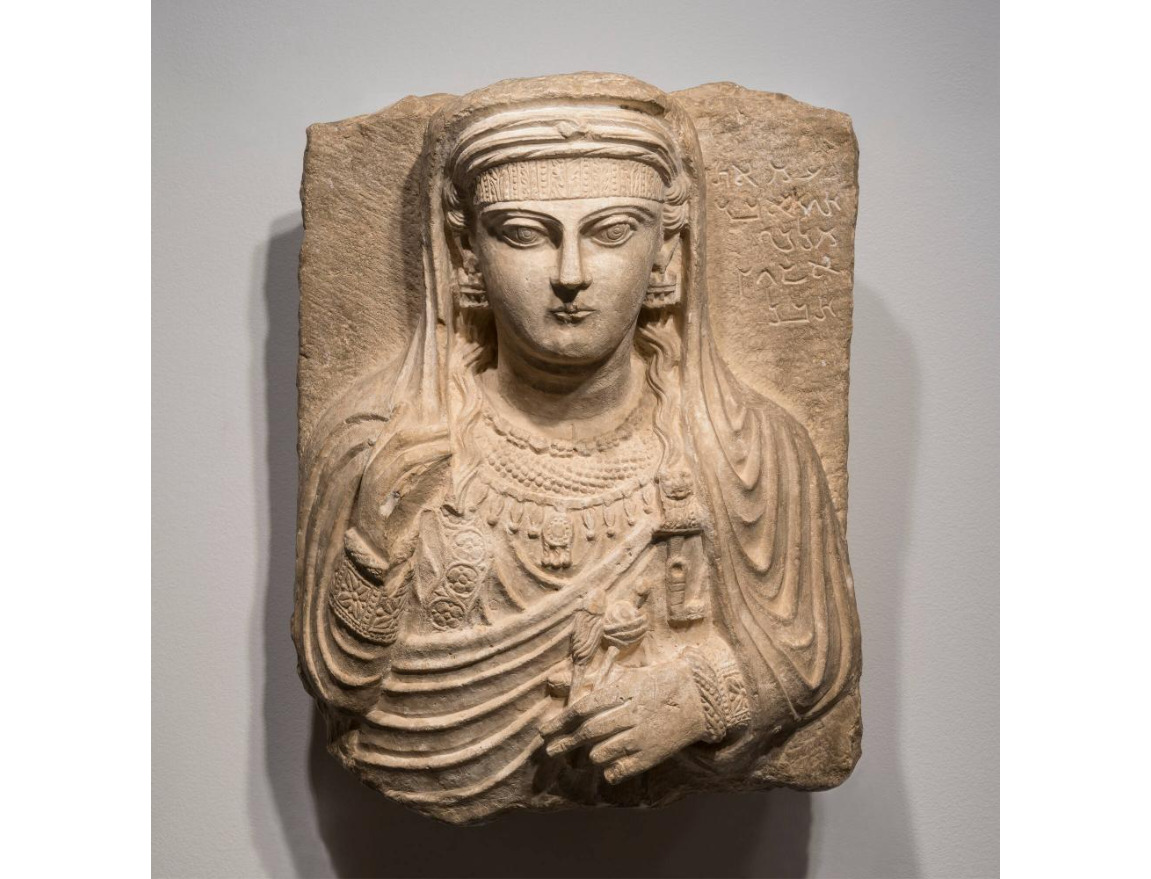

Palmyrene Funerary Portrait. Limestone. Second Century AD. 20.51 × 17.01 in. (52.1 × 43.21 cm) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 02–29.2).

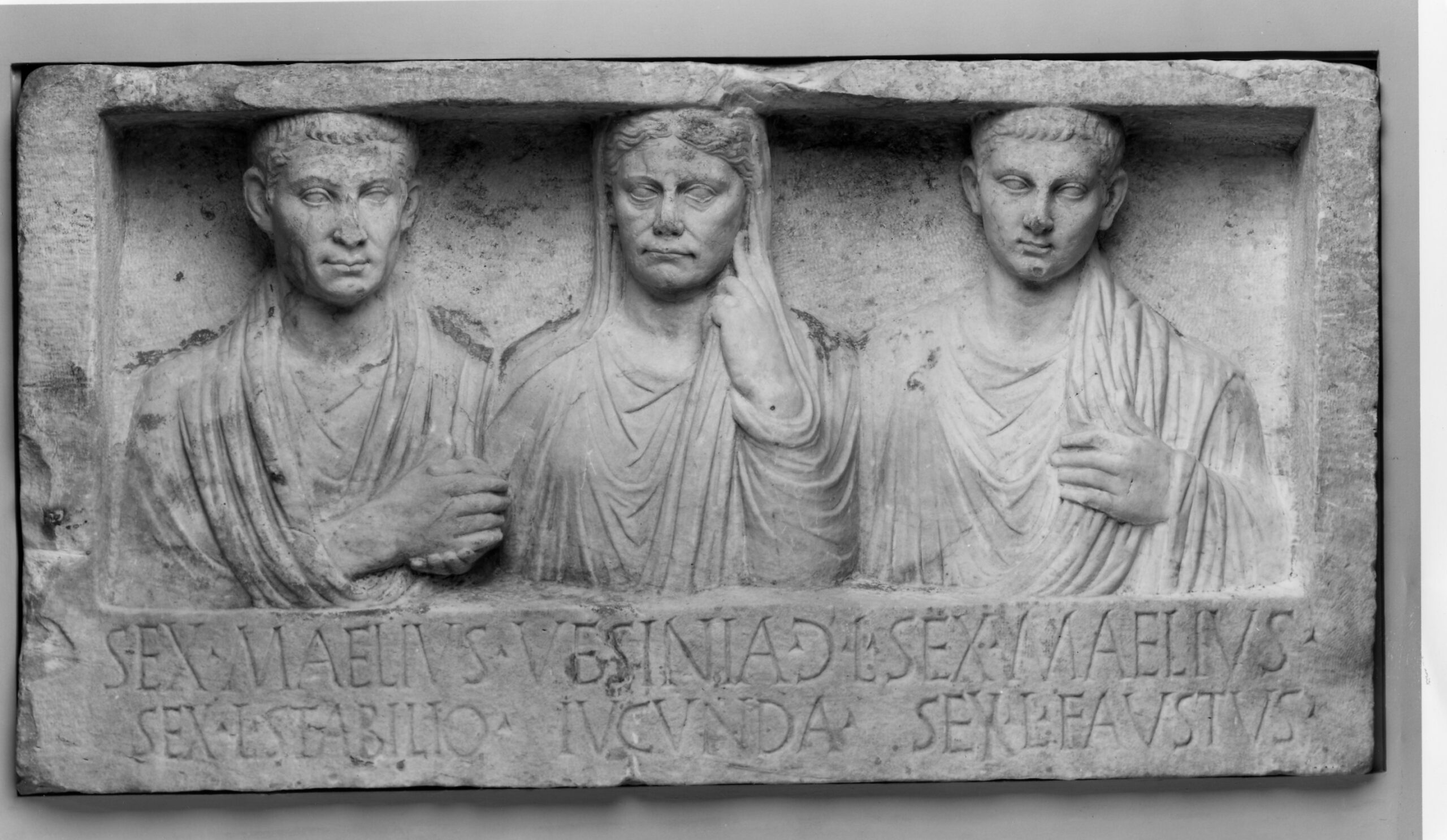

The Palmyrene portraits are not true to life renditions of the actual features of the ancient Palmyrenes in the same way that a modern photograph might be, but they are also not entirely fictitious. They provide information about aspects such as gender, role in the household or community, and family relationships. The style of the portraits is reminiscent of Hellenistic funerary reliefs from Asia Minor and fits broadly into the Roman funerary portrait tradition of the late first century CE. The deceased are depicted from the waist up in a strictly frontal stance, with the arms held close to the body and the name and genealogy given in the accompanying inscription in Palmyrene Aramaic. Similar, although not identical, types of funerary portraiture appear in the early Empire at other sites in the eastern Mediterranean, with well-known examples in Dacia (on the Danube in central Europe) and in the Fayum region of Egypt. The Palmyrene portraits differ from their Roman counterparts because of the emphasis in Palmyra on the individual, albeit in a collective display in the tomb.

Funerary Monument for Sextus Maelius Stabilio, Vesinia Iucunda, and Sextus Maelius Faustus, early first century C.E. (Courtesy of North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina, 79.1.2)

In the female portraits, most women wear a tunic with a cloak draped over the shoulders, a turban and veil covering the head, and a diadem across the forehead. In the earliest portraits, dating to the first and second centuries, women hold objects such as the spindle and distaff, which were tools used in the production of wool yarn. Women also sometimes held babies on their left arm or hung keys from the brooch that held the cloak on the shoulder. It is possible that these objects were used to indicate the woman’s role in the household. Beginning in the mid-second century, women began to raise a hand to the chin or veil in a gesture that has been compared to the ‘pudicitia’ (modesty) gesture in Roman portraiture. They also displayed increasing amounts of jewelry: multiple necklaces, bracelets, rings, earrings, and ornate brooches.

Most of the Palmyrene men also wear a tunic and cloak, with the right arm held in the sling created by the folds created by the draping of the cloak around the body. Like many of the women, men also hold an object in the left hand. The book roll, which may symbolize literacy or citizenship, is most common. Those men who wished to draw attention to their involvement with the caravan trade or protection of the city would display a sword or whip, and priests would hold the jug and bowl used for ritual offerings in the sanctuaries of the city.

Funerary portrait of No-om (?), Wife of Haira, Son of Maliku c. 150 CE. (Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The William A. Whitaker Foundation Art Fund, 79.29.1).

Priests in Palmyra are easily identified by their hat. It is tall and cylindrically shaped and is often adorned with a wreath as well as a miniature bust. In addition to this hat, priests often wear a riding cloak attached on the right shoulder with a brooch. When a Palmyrene male wears the hat on his head, he is always clean-shaven. This pattern is particularly striking after 150 CE, when it was the fashion in Palmyra to have a beard, and it suggests that the dress of priests was regulated in some way. The popularity of the hat, often displayed on a podium or cushion in the background when not worn on the head, indicates that it was a potent symbol of status.

The banquet scenes that became popular in the second and third centuries, CE, demonstrate the importance of portraying the family. These scenes were carved on large rectangular slabs or sarcophagus lids that sealed banks of burial niches in highly visible areas of the tomb. The composition of these large-scale scenes is conventional, with a male or males depicted reclining on his left side on the banqueting couch while holding a drinking vessel in the left hand (in an interesting nod to the East, sometimes this vessel was a shallow bowl in the Parthian style). The reclining figure’s wife or mother would sit on a chair at the end of the couch, and additional family members: children, siblings, grandchildren, nieces or nephews would stand behind him or be depicted in bust form between the legs of the banqueting couch below. The significance of this scene, whether it portrays a funerary banquet, a meal in the afterlife, a ritual banquet, a family banquet, or just a convenient excuse to depict the family all together, has been much debated.

Palmyrene banquet relief. (Palmyra Museum, A 218. Photograph by the author).

These Palmyrene reliefs in many ways resemble formal portraits that one might create in the modern era, with the individual depicted in what is presumably their best attire, some holding objects that communicate something about their identity, and many adorned with brooches, necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and rings. In ancient Palmyra, the portraits of men and women were placed side by side in the tombs; they are more or less similar in scale, they are posed in much the same way, and men and women alike hold objects and are identified by name in the accompanying inscriptions.

Despite the similarity of representation in terms of frontality, size, placement in the tomb, and expense, it would be a mistake to assume that similar styles of funerary commemoration indicate similar importance, agency, or even significance of the portrait. If you pay careful attention to the ways in which men, women, and children are depicted, you notice that male portraits draw attention to themselves and their public activities whereas female portraits highlight the family, by their presence, their attributes, their lineage, and their adornment. These portraits were once part of a greater display, the ensemble of portraits in the tomb, and presumably these images were not only isolated statements about the identity of the deceased, but also contributed to a message about the whole family.

Maura Heyn is Professor of Classical Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

How to cite this article

Heyn, M. 2022. “Portraits of People and Society From Palmyra.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.6. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/heyn-palmyra-portraits/.

Want to learn more?

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Cyprus and Ugarit: A Tale of Two Late Bronze Age Mercantile Polities

Post a comment