Hello I Must Be Going: The ANE Today Editor Says Goodbye

December 2022 | Vol. 10.12

By Alex Joffe

Offspring are sometimes measured in numbers. So, 118 issues, 558 articles, and from 0 readers in 2013 to over 42,000 by 2023? These are ANE Today’s basic statistics, behind which stands, what? Stepping down after a decade as editor is as good a time as any to look back.

There was an idea, that ASOR should have a platform to reach lay readers. The full backstory is a bit more complicated but that was basic concept. It’s not terribly profound, that the premier American ancient Near Eastern studies organization should try and address the public, but it’s actually highly original. To understand why we need to go far back in time, to at least the 1960s.

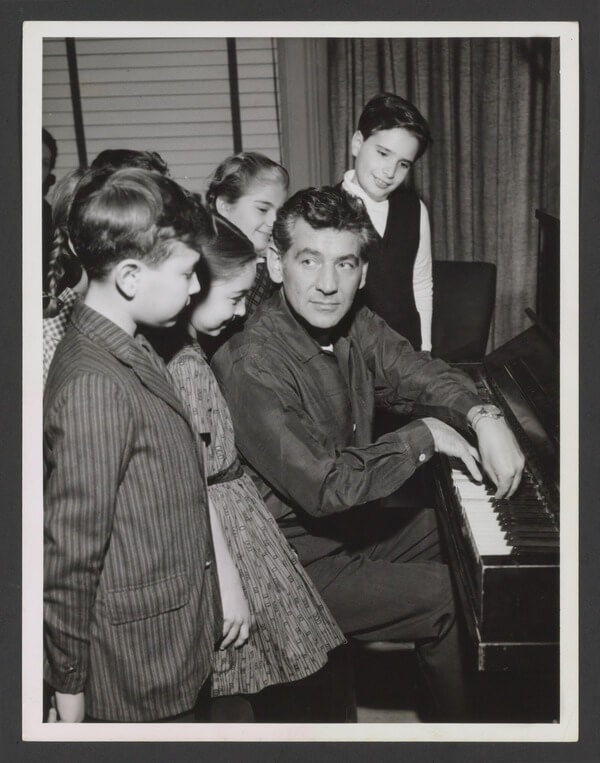

Leonard Bernstein backstage during a Young People’s Concert. Note the young epople to the left and rear. (Library of Congress: Music Collection).

Fundamentally I think the problem has to do with the murder of middlebrow culture by the end of the 1960s (think literature, art and science, delivered, say, by the Book of the Month Club, Saturday Evening Post, and Discovery!, especially those years hosted by the late great Jules Bergman). With it went the idea of a democratic American public culture that was intelligent and integrative (and which included music, arts, history and literature), taught in schools but also communicated by specialists and consumed by the middle class. How and why all this was killed off is an interesting question, mostly having to do with intellectuals and activists demanding rarified highbrow ‘authenticity’ on the one hand and specialists eager to get on with their own specialties on the other. Some of this was of course useful and long overdue. Some of it was not.

So where during the 1960s Leonard Bernstein would patiently explain classical music to children like me on national TV on a Sunday afternoon, by the 1970s this became a highbrow pursuit. By then kids were having their attention spans shortened by Sesame Street while we adolescents went to see the Grateful Dead, which was awesome, but which after a point did not serve the purpose of sustaining a national cultural vernacular and wider sense of participation in a stream of tradition. So, too, with archaeology and ancient studies; in the 19th and early 20th century we were front page news, but by the 1970s, we couldn’t get mugged in this town. More or less the same dynamics went on in most developed countries.

Where have you gone Jules Bergman, a nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

Obviously the full story is much more complicated – the rise of hyper-specialization in the academy, where scholars were trained to work on narrower and narrower topics increasingly in isolation from one another, using increasingly inaccessible language to signal novelty and erudition; the decline of religious literacy on the part of Western audiences, losing touch with the fundamentals of their religious traditions that serve as a draw or reference point for the ancient Near East; the multiplication of publishing outlets for scholars and broadcast outlets for the public, ‘narrowcasting’ specialized fare to smaller audiences; and the emergence of post-colonial theory in academia, which cast the history of Western interest in the world as a function of empire, racism and greed.

Anyway, scholars mostly stopped talking, the academic incentives for communicating were reversed (about which more below), popular media like magazines and cable TV took over (often with academics as talking heads), and the ancient world became increasingly known for pyramids and ice men (the latter of which are rare in the Near East). But even pyramids, ice men, and of course ‘ancient aliens,’ proved there was a market for information.

Thus, ANE Today. The idea was to encourage the broadest sweep of ancient Near Eastern scholars – working from the Atlantic to Afghanistan (more or less), from the earliest humans to the 21st century – to explain to the public what they do in straightforward terms. And as with most things today, the solution was conceived mostly in terms of a web site, social media, and email. The problem was getting scholars involved.

Barton Hall, May 8, 1977. Regarded by some as the greatest Grateful Dead show of all time. I missed it by four months.

Part of the reason is that academia presents few incentives for scholars to communicate to the broader public. You don’t get promoted and tenured writing for the public, or get all-important grants, and not all scholars have the skills and tenacity to make any sort of name doing it. In the English-speaking world of the ancient Near East of the past (so to speak) there was the Sumerologist Samuel Noel Kramer, Biblical Archaeologists William F. Albright and G. Ernest Wright, Yigal Yadin of course, and some others, like V. Gordon Childe and Leonard Woolley, from a long gone, seemingly heroic age. Today we have a few examples, whom I will refrain from embarrassing in public, but they seem noble exceptions. But my view is that all academics should be willing and eager to sit down and write a thousand words about their work in an hour.

Another part of the problem is specialization, that is, the subdivision of research and knowledge into ever-tinier segments. This has made it hard for scholars to comfortably explain their work even to each other, and more importantly, to make that resonate with the public. Then there is the resort to incomprehensible language and ‘theory’ as a display of erudition (its harder to be challenged if people can’t figure out what you’re actually saying). And archaeology today is (or rather, uses) more hard science than ever (physics, chemistry, biology, etc.), but explaining why new techniques are exciting is a challenge. But even for ‘traditional’ scholars or issues, the challenge is there. Just why is what you’re doing interesting or maybe even important? How do you shorten the distance between past and present and provide meaningful information that enhances the life experience, whether intellectually, aesthetically, or emotionally?

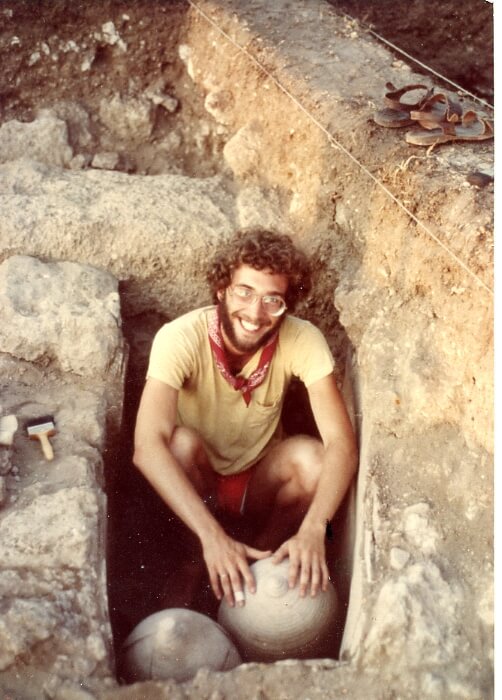

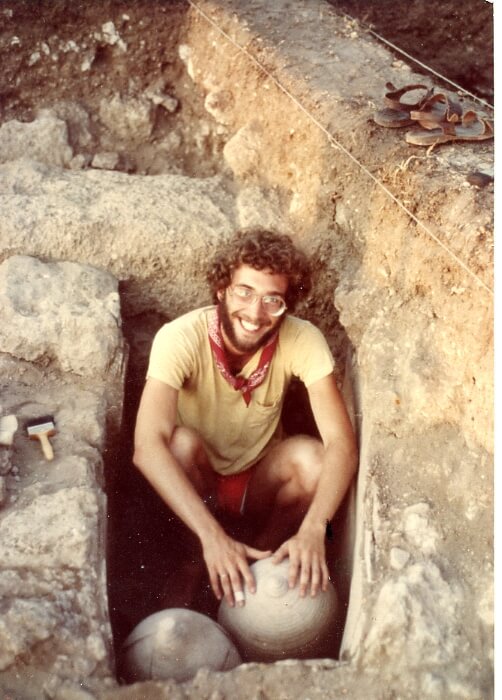

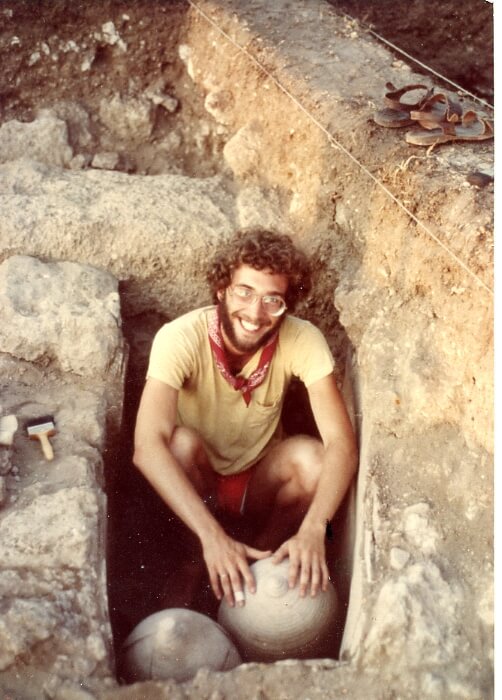

Tel Dor 1980. Portrait of the editor as a svelte young man.

From the point of view of an editor, myself for example, this is a multi-step process. Step one is finding the writer. This means scouring books, journals, web sites, and the like for interesting and new work, and wondering, can this be made interesting (and accessible). Every baby is beautiful to its parents, just not necessarily to the rest of us. Overall this has meant reading zillions of publications in fields far from my own. But as I have repeatedly reassured people who are either impressed with my erudition or concerned with my mental health, fortunately, I retain very little.

Step one and a half is approaching scholars, trying to entice them with the prospect of explaining and publicizing their work to a broader audience. This has meant, literally, thousands of emails. Step one and three quarters are hundreds more emails begging, cajoling, and guilting them into actually producing.

Step two is taking what they’ve written and actually making it accessible. Sometime it’s merely a matter of changing punctuation; other times it’s a full translation job, from academic-speak into something hopefully resembling English. The issue isn’t merely taking German-English or Hebrew-English and making it flow (and heaven knows I could not write anything intelligible in those languages or any other). Rather it is to try and bring out the facts and ideas embedded in the piece while helping the author’s voice be heard throughout. Sometimes it’s easier than others. I’m pleased to say that after 500+ pieces, only two authors complained about my editing. So, yay for me, I guess.

Tel Dor 1980. Portrait of the editor as a svelte young man.

But there is also the matter of controversy. This has two dimensions. The first is politics, and the astute reader will note that we stay away. There are only three issues on which we’ve taken an explicit political stance, ISIS, antiquities looting, and Putin. We’re against them; hopefully you are too. But while other areas are problematic (as academics say), there is no percentage for us to take stances on all issues. No doubt our more politically oriented colleagues object; indeed, not taking a political stance in academia these days is deemed as taking a stance. See? There’s no winning. But politics has imperiled huge swaths of academia, not least of all by alienating the public that has its own informed opinions about things, doesn’t like to be hectored and/or badgered, and turns to ANE Today precisely as a refuge from the spiteful deluge of the present. Thus I have refused to go there, and I say this as someone who has written more than his share on political issues elsewhere, aimed not at academics but politicians and policy makers, as well as the public.

Anyway, speaking of controversy, there is also the question of intellectual controversy, Since we’ve had reputable scholars writing for us, these have been few and far between. I recall one grave incident related to the absence of footnotes, and another where I was accused of having utterly ruined the field of Egyptology. Oops. My bad. But these controversies are instructive; they speak to academics and their sometimes inflated senses of ego, pretentiousness, and almost total lack of anything resembling a sense of humor, all of which mask either deep insecurity or genuine arrogance. My advice to them is, lighten up Francis. And, dear reader, please, demand this from academics in your family and ones you meet socially. If necessary, pelt them with dinner rolls.

Megiddo 1996. With Israel Finkelstein and Oded Lipschits. Nice guys. I wonder what they’re up to?

But for me there was also another more personal motive for becoming involved with ANE Today. Too many academics fall into a state where they take things for granted. The opportunity to teach, do research, and even read widely, is rare, and while there are onerous aspects (like raising money, grading, and departmental committees), to my mind it comes with an obligation to give back, to explain why you should be doing this in the first place. Why is what you do interesting, how would you explain it to your mother, I would always ask writers. Frankly, my chance was cut short (buy me a drink some time and I’ll tell you the story), and this has been a sort of second shot, albeit an attenuated one, filled with echoes of what could have been. Anyway, I remain convinced that studying the past is a socially useful thing to do. But it is a privilege, not a right.

So academics, sit down and write something aimed at your mother. Explain why what you do or what you’ve found is cool and exciting and new and important. Give the reader some of your enthusiasm, in words we can all understand. You owe it everyone and also to yourselves, as a matter of self-preservation and self-respect.

And dear reader, please keep reading ANE Today (which is sure to thrive under its new editor Jessica Nitschke) but up your demands from academics. You pay for all this, through tuition, tax dollars and gifts to your alma maters, not to mention tax and inheritance laws, so demand an explanation. Be polite, but insistent. There is very little reason for all these disciplines to exist (that you pay for, did I mention that?) if they don’t include you. This isn’t the 13th century you know, when monks and nuns had all the knowledge locked up in their libraries.

Tell Abel Bet Maachah, 2019. With Rachel Hallote and JP Dessel. Together they are This Week in the Ancient Near East.

Demand to know what’s going on, and you can even politely ask to be part of it all. Go on excavations (at least in the safer countries, but please, don’t buy bullwhips and that sort of thing. I saw that a few times back in the day and it was pretty embarrassing for everyone). Go to conferences, listen, and ask questions. Audit university courses, encourage your college age kids to take courses. And read everything you can, ANE Today of course, but also books and journals. Maybe that way we can all save the humanities from extinction.

Editing ANE Today hasn’t always been fun or easy. You go and deal with academics and see if you like it. More substantively, it was an experience where I got to see much of what scholars are doing, but which I could not do myself. That was painful, a study in the archaeology of heartbreak. But at the end I feel we’ve created something of value. I hope you feel that way too.

Alex Joffe was the founder and editor of Ancient Near East Today from 2012 to 2022.

How to cite this article

Joffe, A. 2022. “Hello I Must Be Going: The ANE Today Editor Says Goodbye.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.12. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/joffe-hello-goodbye/.

Want to learn more?

Ten Fascinating Discoveries in Near Eastern and Mediterranean Archaeology in 2024

Ten Exciting Discoveries in Near Eastern Archaeology in 2023

Post a comment