“The Egyptian,” King of Moab

March 2023 | Vol. 11.3

By Mattias Karlsson

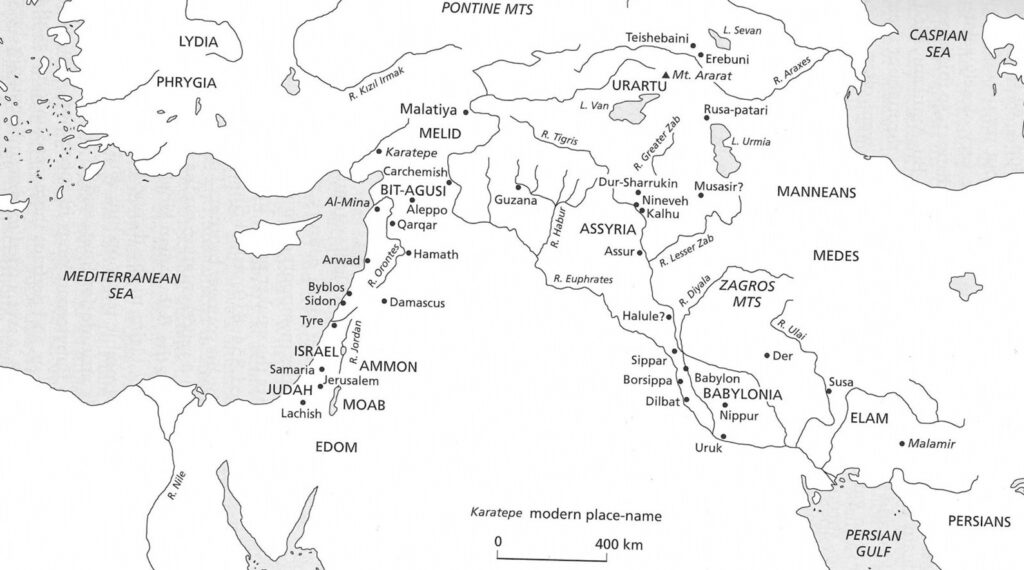

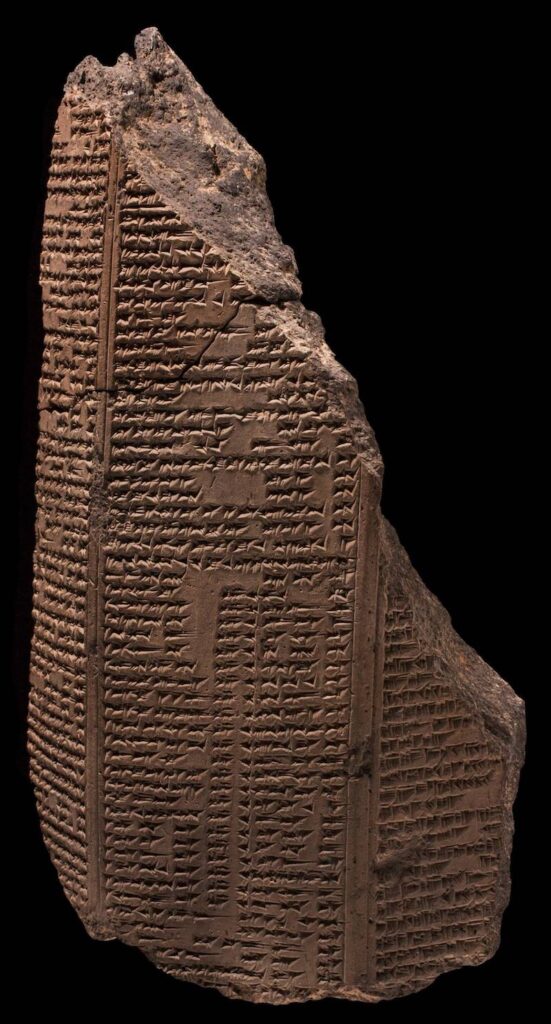

The royal inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian kings Esarhaddon (680–669 BCE) and Ashurbanipal (668–631 BCE) mention a king of Moab named mMu-ṣur-i/Muṣurī — generally translated “the Egyptian”, as Muṣur is a common term for Egypt in the Neo-Assyrian corpus — as providing material resources to Esarhaddon and as participating in one of Ashurbanipal’s military campaigns. The name of the Moabite ruler is puzzling, considering the geographic and cultural distance between Egypt and Moab, which is centered in modern-day Jordan. Contributing further to the puzzle is the fact that the king in question is not mentioned in any of the few preserved Moabite inscriptions, nor in any other ancient text written in a non-Akkadian language. Assuming that Muṣurī really means “the Egyptian”, how are we meant to understand this name?

Map of the Ancient Near East in the Iron Age. (After van de Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East (2016), p. 225).

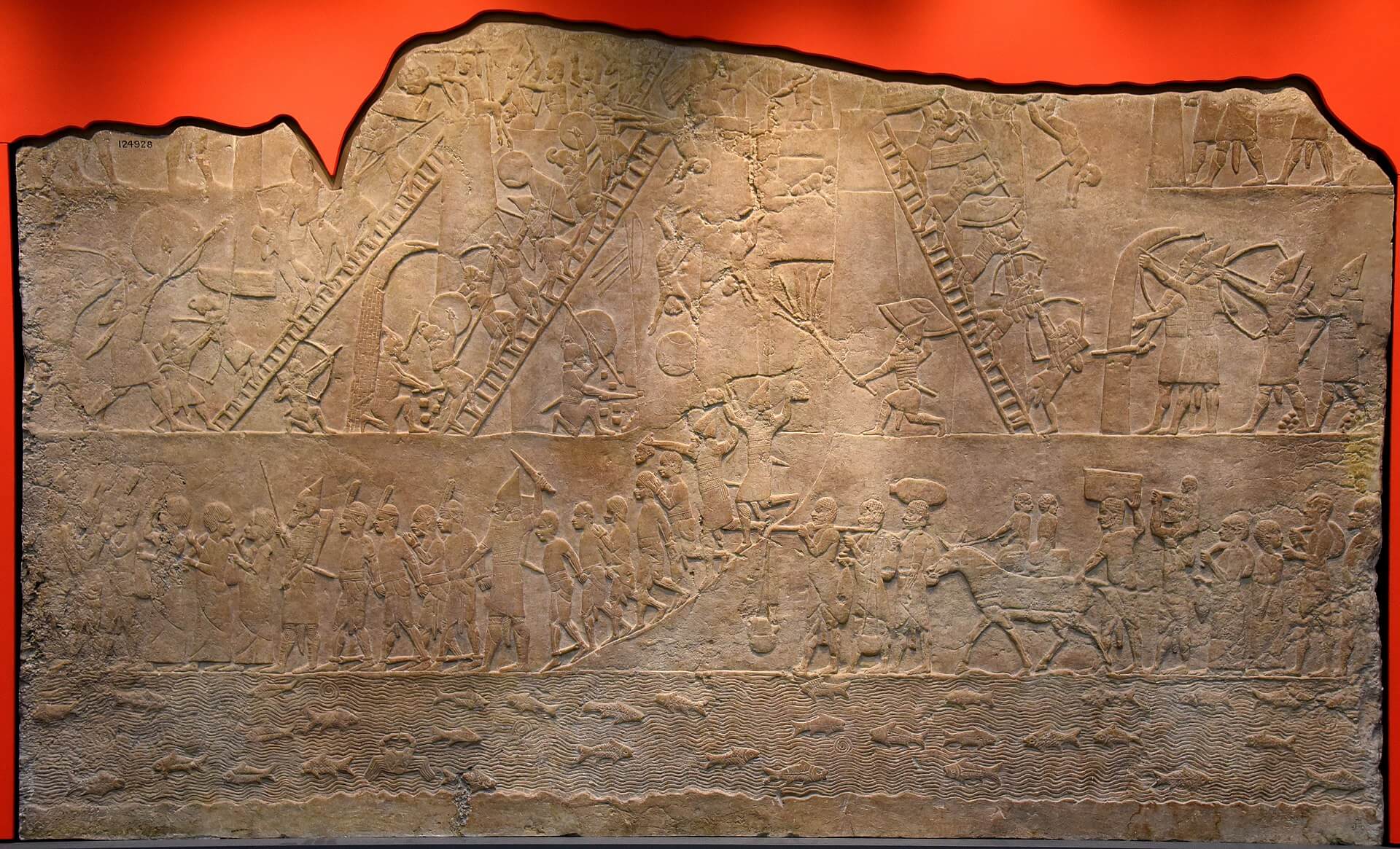

In a royal inscription commissioned by Esarhaddon, the said king narrates that he summoned “the kings of Ḫatti and Across the River” (šarrāni māt Ḫatti u Eber nāri), namely the rulers of the Levantine states Tyre, Judah, Edom, Moab, Gaza, Ashkelon, Ekron, Byblos, Arvad, Samsimurruna, Bit-Ammon, and Ashdod, defined as “twelve kings from the shore of the sea” (12 šarrāni kišādī tȃmtim), as well as ten kings from Cyprus, and that he ordered these rulers to send exclusive timber and stone for a palace construction in the capital city Nineveh (RINAP 4 1, v 54–vi 1).

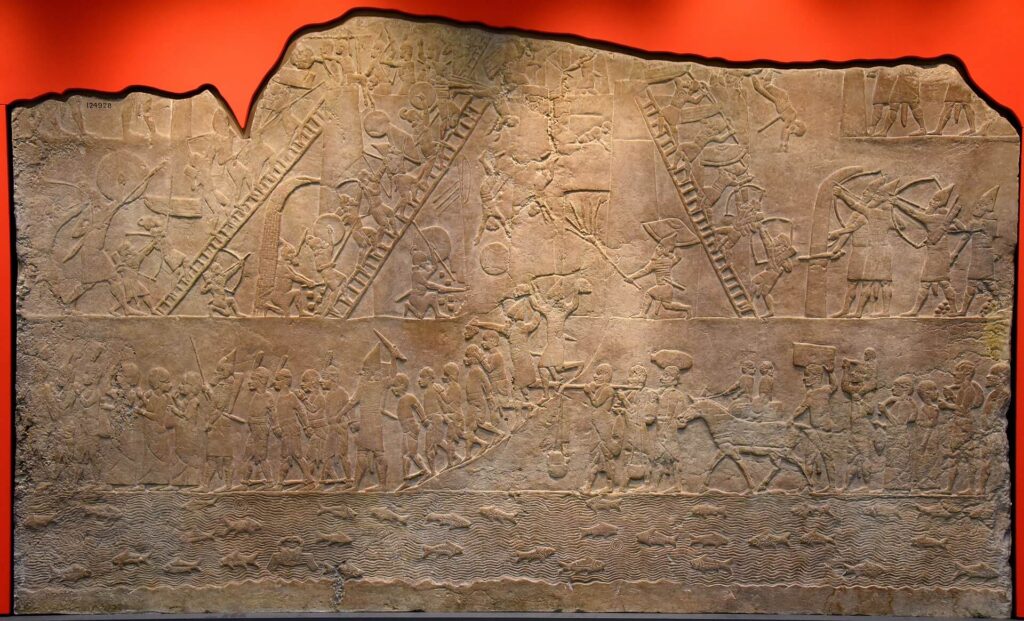

In a royal inscription commissioned by Ashurbanipal, the said king narrates that virtually the same rulers, listed in the same order and defined as “twenty-two kings of the seacoast, the midst of the sea, and dry land, [serva]nts who belonged to me” (22 šarrāni ša aḫi tȃmtim qabal tȃmtim u nābali ardāni dāgil pānīya), carried “their substantial audience gifts” ([tā]martāšunu kabittu) before Ashurbanipal as well as kissed Ashurbanipal’s feet. The Assyrian king then makes these rulers, along with their forces and boats, “take the road (and) path” (urḫu padānu u[šaṣbis]sunūti) with the Assyrian troops by sea and on land. In Egypt, the coalition force defeats the troops of Taharqa (king of Egypt and Kush) in a great pitched battle (RINAP 5/1 6, ii 25´–66´).

Presuming that mMu-ṣur-i really means “the Egyptian”, there are two ways of understanding this name. Firstly, it can refer to the Moabite ruler as of Egyptian ethnicity. Muṣurī may here have been an Egyptian prince installed as an Assyrian vassal, or the son of an Egyptian wife (or concubine) of his father and predecessor on the Moabite throne. Alternatively, the name does not tell of ethnicity but simply refers to the ruler as Muṣurī because he was heavily influenced by Egyptian culture or on account of his sojourn in Egypt.

If the name Muṣurī indicates he was ethnically Egyptian, this ruler may have been an Egyptian prince installed as an Assyrian vassal. The relevant sources do not state this, although parallels can be drawn. Sennacherib narrates that he took Egyptian princes (mārē šarri) as captives in the battle at Eltekeh in 701 BCE. Associated with this narration, a man with the Egyptian-Libyan name Šusanqu is referred to as the son-in-law (ḫatan šarri) of Sennacherib in a document from Nineveh. The Egyptian ruler Necho I (672–664 BCE) is taken as a prisoner to Nineveh, where he is pardoned and reinstalled as Assyrian vassal in Egypt. His son, Psammetichus I (664–610 BCE), is given an Akkadian name (Nabȗ-šēzibanni) and is installed as the ruler of a city in Egypt. All this does not prove that Muṣurī was an Egyptian prince, only that the practice of taking Egyptian princes as hostages and giving them authority within the Neo-Assyrian empire is attested. At the same time, a practice of placing Egyptian princes as Assyrian vassals in states outside of Egypt is, to my knowledge, unattested elsewhere.

Still identified as Egyptian, Muṣurī may also have been the son of an Egyptian wife or concubine of his father and predecessor. Again, the relevant sources do not state this, although parallels can be drawn. The Old Testament claims that king Solomon took an Egyptian princess as wife, in order to seal an alliance between Egypt and the early Hebrew state (1 Kings 3:1). Of course, this stands in marked contrast to the custom in Egyptian classical times during which Egyptian princesses were not given away in diplomatic marriages and it was the Egyptian king who was the one receiving princesses from other states. This may be a reflection of Egypt’s loss of status after the end of the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BCE). Anyway, the mentioned reference in the Old Testament points to the possibility that the Moabite ruler might have married an Egyptian princess. At the same time, the political situation in Egypt in the first half of the 7th century BCE (with Kush or Assyria dominant) was not the same as that in the 10th century BCE (with Egypt being decentralized). Furthermore, we should be cautious about relying on a piece of information provided by the highly ideological Old Testament.

Moving away from the idea of Muṣurī as ethnically Egyptian, it is also possible that the name in question was given due to a great interest in things Egyptian that either Muṣurī or his father might have had. Again, the relevant sources do not prove this, but indications that Egypt was influential and prestigious in the Levant are frequent. At the time of New Kingdom Egypt, Bronze Age Moab was controlled by Egypt, and this naturally led to some degree of Egyptian cultural influence. Material evidence of contact with Egypt, and influence from Egypt, has been found in Phoenicia (notably Byblos), Ebla, and Ugarit. The Old Testament frequently refers to Egypt as a power to be reckoned with in the foreign relations of Judah and Israel. In short, Egypt appears as greatly influencing the Levant, both in the Bronze and Iron Ages. It has also been suggested that there was an “Egyptomania” in Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian empire, according to which all things Egyptian were regarded as exclusive and prestigous. In accordance with such a phenomenon, the royal inscriptions of Ashurbanipal include a reference to the Assyrian army seizing obelisks from Thebes. In other words, it is plausible that a Moabite ruler was also under the influence of “Egyptomania”. At the same time, Moab is often characterized as culturally distinct and more focused on relations with its immediate neighbors.

Again proceeding from the idea that Muṣurī was not necessarily an Egyptian, the Moabite ruler in question might have received his name (as an agnomen) because of his participation in Ashurbanipal’s first Egyptian campaign. The coalition which Muṣurī was a part of was successful in its aim, and the Moabite ruler may have been hailed in his returning home to Moab from Egypt as a conqueror and in possession of exotic booty that gave him prestige in the eyes of the Moabites. A parallel may be drawn with the Roman custom of giving agnomen to Roman military commanders who had been successful in their respective regions, e.g. Germanicus, Britannicus, and Scipio Africanus.

A problem with this interpretation is that the name was given already by Esarhaddon, before the first Assyrian conquest of (northern) Egypt in 671 BCE. It is possible, though, that Muṣurī also had joined Esarhaddon’s failed attack on Egypt in 674 BCE, but with the texts not recording this. At the same time, such an assumption belongs to the realm of speculation. Furthermore, it is naturally not self-evident that a custom in the Roman empire automatically can be transferred to the Moabite state.

In conclusion, the name Muṣurī in the context of Assyrian royal inscriptions continues to elude us. Although it is highly likely that the personal name really means “the Egyptian” (identifying a Moabite gentilic), we are left to speculate (until new evidence emerges) as to why such a name was given to a Moabite ruler. This paper has put forward some suggestions, proceeding either from the idea that Muṣurī was an ethnic Egyptian or from the notion that he was closely related to Egypt in some other way. No doubt, the discussion on the meaning of the name Muṣurī in the present context will go on.

Mattias Karlsson is an Assyriologist and the author of From the Nile to the Tigris: African Individuals and Groups in Texts from the Neo-Assyrian Empire (Eisenbrauns, 2022).

How to cite this article

Karlsson, M. 2023. “‘The Egyptian,’ King of Moab.” The Ancient Near East Today 11.3. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/karlsson-egyptian-king-moab/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Post a comment