The Neo-Assyrian Empire and Egypt

August 2022 | Vol. 10.8

By Mattias Karlsson

The Neo-Assyrian empire, with its center along the river Tigris in northern Mesopotamia, controlled large parts of the ancient Near East. For a decade or so, Assyria even controlled Egypt with its age-old civilization. Assyrian royal inscriptions, Babylonian chronicles, and Assyrian documents are the primary sources for this period.

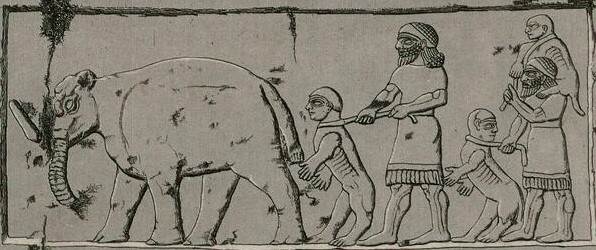

Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions initially speak of battles and tribute with regard to Assyrian-Egyptian relations. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858-824 BCE) narrates on his so-called Black Obelisk that his troops defeated a Levantine-Egyptian coalition at Qarqar in Syria 853 BCE. A register on the same monument shows Egyptian tribute in the form of exotic animals being offered to Shalmaneser III.

The Assyrian kings Tiglath-pileser III (744-727 BCE) and Sargon II (721-705 BCE) both boast about having moved the border of the Neo-Assyrian empire to the threshold of Egypt. Sargon II states that he defeated the rebellious ruler of Gaza and his Egyptian auxiliary troops at the battle of Raphia in 720 BCE. He also claims to have encouraged trade between Assyrians and Egyptians by establishing a harbour close to Egypt, and to have received tribute consisting of large horses from a king of Egypt, probably Osorkon IV, a ruler from the Nile delta.

Egyptian tribute offered to Shalmaneser III. From A.H. Layard, The Monuments of Nineveh, 1849, pl. 55. Public Domain.

Sargon II also mentions that an anonymous Egyptian king had been approached by Levantine kings, who sought a powerful ally in their struggle against the Neo-Assyrian empire. Last but not least, Sargon II claims to have received the rebellious ruler of the Levantine city Ashdod from the hands of the Kushite (Sudanese) king, who by this time controlled Egypt. The inscriptions of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (704-681) tell of a military clash at the Levantine city Eltekeh in 701 BCE between Assyrian forces and a Levantine-African coalition. According to the Assyrian account, the Egyptian and Kushite troops were defeated and many were taken as prisoners of war.

Both Assyrian royal inscriptions and Babylonian chronicles tell of Assyrian-Egyptian relations in the later Neo-Assyrian period. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon (680-669 BCE) made an unsuccessful attempt to conquer Egypt in 674 BCE, only succeeding three years later. The important Egyptian city Memphis (near today’s Cairo) was conquered and sacked, and the Kushite king Taharqa (690-664 BCE), who controlled Egypt up to that point, fled southward. Members of the family and court of Taharqa were taken as prisoners of war, inluding his crown prince Ushanahuru. It is probably the latter who is depicted kneeling at the feet of Esarhaddon on the Zincirli Stela. An Assyrian administration was imposed on Egypt, in the sense that Egyptian vassals were appointed, taxes were established, and Assyrian garrisons and officials were installed.

Assyrian relief showing an Egyptian fort. BM 124928. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A rebellion, supported by Taharqa, soon broke out, and Esarhaddon initiated a military campaign to Egypt in 669 BCE. But the Assyrian king died on route and the campaign was halted. It was then up to his son and heir, Ashurbanipal (668-631 BCE) to re-conquer Egypt in 667 BCE. Memphis was re-conquered, Taharqa fled southward once again, and the Assyrian vassals in Egypt were re-appointed.

Not long after this event, a conspiracy among these vassals was revealed by Assyrian officials in Egypt, and the conspirators were either executed or punished and then pardoned. The Egyptian ruler (of Sais and Memphis) Necho I (672-664 BCE) was taken to the Assyrian capital Nineveh, where he subsequently was pardoned, crowned, and sent back to Egypt as Assyria’s main ally in Egypt.

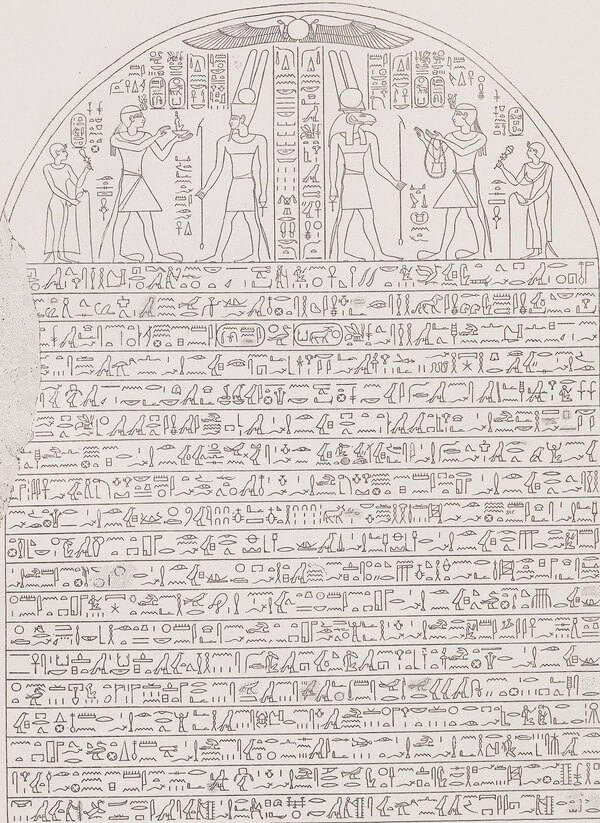

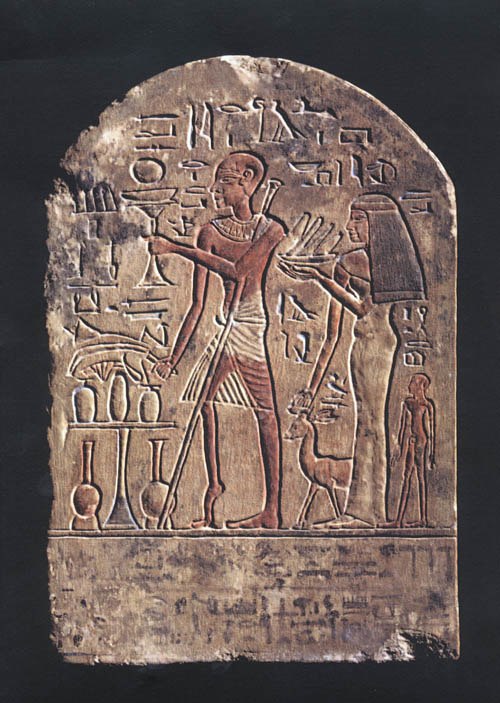

In 664 BCE, the new Kushite ruler Tanutamon (664-656 BCE) managed to re-conquer northern Egypt, as narrated in this king’s so-called Dream Stela, which seems to include veiled references to Assyria. Ashurbanipal heard the news and dispatched his army. According to the Assyrian account, the Assyrian forces managed to defeat the Egyptian-Kushite troops, marched all the way to southern Egypt, and sacked the important city Thebes. Tanutamon fled southward, to Kipkipi, probably situated in Kush (Sudan) proper. Necho I supposedly died in battle and was replaced by his son and heir Psammetichus I (664-610 BCE) as Assyria’s main ally in Egypt. Ashurbanipal states that he re-affirmed the positions of twenty Egyptian vassals (from the delta in the north to Thebes in the south) and made their oaths of allegiance stronger than before.

Dream Stela of Kushite ruler Tanutamon. From A. Mariette, Monuments divers recueillis en Egypte et en Nubie, 1872, pl. 7. Public Domain.

A combination of factors, such as skilled maneuvering by Psammetichus I, the relative weakness of Kush, and Assyria’s problems on other fronts of the empire, led to Psammetichus I emerging as the sole ruler of an independent Egypt, inaugurating the Saite period of Egyptian history (664-525 BCE). Psammetichus I was recognized as the ruler also of southern Egypt in 656 BCE by the appointment of his daughter in a vital cultic office, and he is referred to in the later inscriptions of Ashurbanipal as someone who had “cast off the yoke of Assyria”. At the end of the reign of Psammetichus I, the Neo-Assyrian empire crumbled (and ultimately fell) at the pressure from Babylonian and Median forces, and Egypt actively supported Assyrian troops in the latters’ struggle in the Levant against the Neo-Babylonian state around 610 BCE. Babylonian chronicles tell of this final stage of Assyrian-Egyptian relations.

The Neo-Assyrian empire employed a tactic of mass deportation of conquered peoples, and Assyrian documents paint a picture of the lives of Egyptians (and Kushites) in Assyria. Some of these people have Egyptian names, others are revealed as Egyptians (or Kushites) by ethnonyms or textual contexts. The Egyptian presence was especially strong in the city of Assur, but there appears to have also been an Egyptian community in Nineveh. The documents refer to loans, purchases, and other kinds of transactions and give a glimpse of the lives of exiled Egyptians (and Kushites), men and women, old and young, high and low.

It has been proposed that there was an “Egyptomania” in Assyria of the Neo-Assyrian period, in the form of import of Egyptian goods and people. A vast number of ivories with Egyptian(ized) motifs have been found in the Assyrian city of Kalhu. Assyrian royal inscriptions and documents narrate that Egyptian scholars and scribes were brought to the Assyrian court. Also, Neo-Assyrian art (such as wall reliefs and “obelisks”) is believed to have been inspired by Egyptian art.

Ivory funiture inlay with Egyptian motif from Kalhu. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 62.269.3. Public Domain.

The Assyrian administration in Egypt was focused on indirect rule, in the sense that the Assyrian kings entrusted local Egyptians to rule Egypt on the conditions that these were loyal to the empire and provided material resources to Assyria. As noted above, twenty Egyptian rulers and their jurisdictions are enumerated, indicating that the Assyrians were interested and knowledgeable in Egyptian affairs. At the same time, there is no indication that the Egyptians who lived in Assyria were especially privileged (nor discriminated against). Furthermore, Assyrian royal inscriptions and Babylonian chronicles tell of the slaughter of Egyptians and of the destruction of Egyptian cities. For Assyria, Egypt was simply another rival to be subjugated, and its people incorporated into the empire.

Mattias Karlsson is associated with the Disciplinary Domain of Humanities and Social Sciences, Faculty of Languages, Department of Linguistics and Philology at Uppsala University.

How to cite this article

Karlsson, M. 2022. “The Neo-Assyrian Empire and Egypt.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.8. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/karlsson-neo-assyrian-egypt/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

When Is It Ok to Recycle a Coffin? The Rules of the Reuse Game in Ancient Egypt

Post a comment