Goddesses of Myth and Cultural Memory

may 2022 | Vol. 10.5

By Emilie Kutash

Goddesses, it seems, are still among us today. The contemporary goddess movement reflects a quest for an antidote to male divinity and a means to enact a woman-centered religious practice. But goddesses are far more pervasive and far older. Goddesses of Myth and Cultural Memory documents the presence of goddesses in a wide range of literature, philosophy and theology across the centuries. They appear in such divergent contexts as Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Kabbalah, Medieval allegory, and in our time, feminist and psychoanalytic literature.

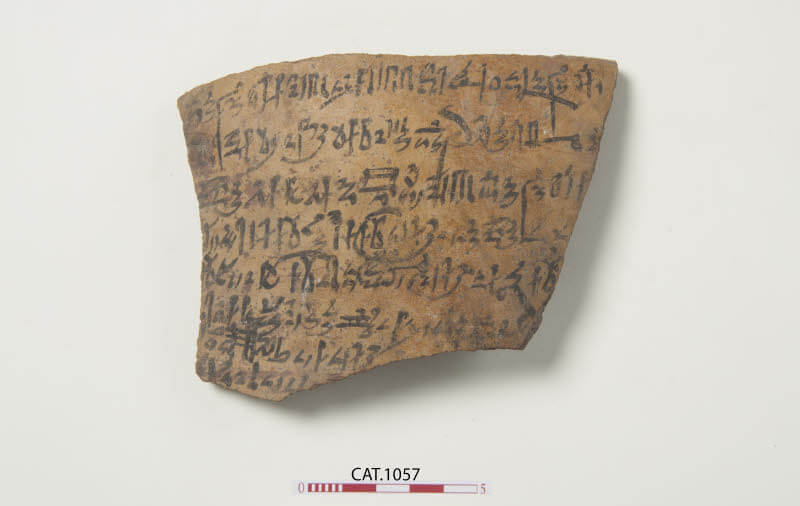

Many scholars including Walter Burkert, Carolina López-Ruiz, M. L. West, Jenny Strauss Clay, G. S. Kirk and others have found precursors to the goddesses described in Hesiod, Homer, and the Homeric hymns in Mesopotamian and Near Eastern texts. Akkadian, Sumerian and Hittite texts document a common heritage. There are similarities between the Hurrian creation myth, for example, and the Greek mythology of Ouranos, Kronos, and Zeus. Love and war, virginity, promiscuity, bloodthirstiness, and theogonic fecundity did not originate with Hesiod.

Goddesses of Myth and Cultural Memory. Book by the Author.

Goddesses have ancestors: Inanna in Sumer, Ishtar in Akkad, Anath in Canaan, and others possess characters similar to the later Hesiodic and Homeric figures.The oldest known to Western scholarship was Inanna, the great Sumerian goddess of love and war. It is clear, however, that much of the goddess lore that appears in subsequent communities is the ‘literary’ version elaborated in Hesiod, Homer, and the Homeric Hymns. While statues and sacred biographies attest to the presence of goddesses as objects of worship in long-gone cultures, their powerful presence in the Archaic and Classical literature of Greece is what ensured their continued survival. Most of what is discussed in Goddesses of Myth and Cultural Memory, then, addresses a persistent and perennial reception, the allegorizing and reinterpretation of ancient myths of archaic and classical Greece.

Egyptologist Jan Assmann, building on the work of French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, suggests cultural memory persists over millennia. The evolution and reception of goddess mythology in a variety of interpretive communities exemplifies this. Hesiod’s Theogony, Homer, and the Homeric hymns are our sources par excellence for a colorful and exotic array of goddess prototypes. The pantheon is populated by a goddess of the crossroads, of fertility, of the wild, a queen of night, and a guide between the underworld of the dead and the world of the living. There are wives, mothers, and virgins, and a celebrated goddess of love.

Ishtar from Eshnunna. Terracotta relief, early 2nd millennium BC. Louvre, AO 12456. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons. CC-BY-2.5.

Athena, born from the head of her father Zeus, is a virgin and is known as the goddess of wisdom and war. Hekate is an honored Titan who guides Persephone from the world of Hades after her abduction. Hera, the wife of Zeus and a mother goddess, possesses life-giving fertility, as do Kybele and Rhea. Artemis is a goddess of the wild and Gaia the sole origin of most of the progeny that populate the theogonic genealogy that follows. Hesiod’s lovely goddesses of “golden sandals” and “dazzling gifts” continue to play prominent and often conflicting roles on the world stage. What were forbidden idols for the Hebrews and Christians for example were named “mother of the gods” by the Romans.

There were also exotic and strange allegorical and symbolic interpretations of ancient mythology. Platonists and Neoplatonists of late antiquity treated goddesses as place-holders for the highest categories of philosophical truth. During the first and second centuries CE, a fusion of exotic literature and Platonic philosophy, so-called Egyptomania, a backlash against Stoic and Epicurean skepticism and a revitalization of the Chaldean Oracles, gave classical mythology new life. Now the very creation of the world was due to mediating goddesses whose ‘fertility’ was instrumental to her role in receiving intellectual paradigms, and using them to produce the world. These philosophical goddess enactments were central in Platonist dualism, in the triads of Gnosticism and Neoplatonism, and focused on the omnipresent goddess’s ‘fertility.’

Relief of Pensive Athena, 400 BC. Athens, Akropolis Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

References to Asherah, Sophia and Shekinah might suggest there were goddesses even in Hebrew contexts. The discussion looks critically at archeological finds, apocryphal texts (where there is clearly a “goddess of wisdom” in the form of “Sophia”) and the Kabbalist concept of “Shechinah.” But how did Christianity make the goddesses disappear? In the Late Roman Empire, the hegemony of Christianity treated goddesses as anathema to the canon. They were regarded as examples of shameful behavior and certainly no part of a ‘masculinized’ trinity. In Gnostic and Neoplatonist literature, a female presence mediates the higher and lower elements in the philosophical triad. In Christian theology, a neutered Holy Spirit mediates the Trinity. Scholars continue to debate the possible connections between the literature of the church fathers and that of Gnosticism. Some scholars make analogues between Christ and Sophia or associate Mary, mother of Christ, with goddess prototypes, while others suggest a relation between the popular Isis phenomena during formative Christian years and Christ as a savior.

Though goddesses were expunged from all early Christian settings, medieval allegorists promptly recreated them in the form of ‘Natura’ and ‘Sophia,’ allegories supporting Christian ideas. Goddesses survived into modernity as well. In the eighteenth century a quest for the secrets of nature and the mystery of being held the ‘veiled ‘goddess to be a figure of concealment and revelation. Finally, for some psychoanalysts, feminist scholars and for actual goddess worshipers, goddesses are an antidote to the so-called logocentrism of western culture and the masculine image of deity.

Though cultural memory transforms as priorities change with varying interpretive communities, one feature remains the same whether in ancient, medieval or modern or contemporary use. Gender essentialism never seems to go away. The male gender, in every context, is associated with light, permanency, intellect, and aloof and exempt unity, and the female with darkness, reproductive fecundity, change, and motion. The less valued, but necessary traits of movement and change entail discontinuity, disunity, and are associated with nature and the female.

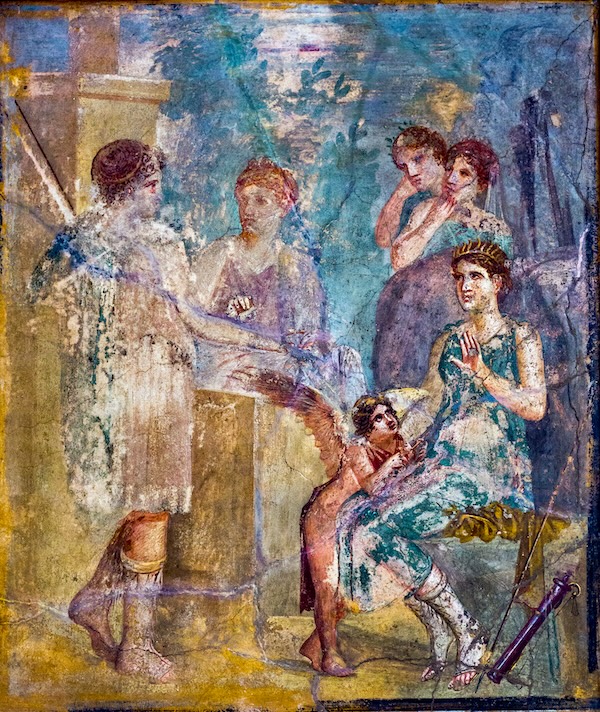

Seated Artemis with Callisto and Eros form Pompeii. Used under CC BY-SA 4.0, created by, ArchaiOptix.

The eternal, unmoving, unmixed ‘intellectual’ qualities are a higher more valued reality. Jung’s anima and animus, for example, specifically incorporates goddesses, along these lines, while other psychoanalysts and feminist philosophers either employ or deconstruct similar binary oppositions. One of the claims, then, of Goddesses in Myth and Cultural Memory is that we need to understand that mythology concerning gender persists and continues its long life, precisely along the same lines as it did in the texts of its ancient predecessors. The book leaves the reader with a compelling question. What is the mysterious power possessed by ancient myth that has allowed it to prevail even in face of all attempts to devalue it as scholarly discourse?

Emilie Kutash is a Philosophy Instructor at Salem State University.

How to cite this article

Kutash, E. 2022. “Goddesses of Myth and Cultural Memory.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.5. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/kutash-memory-goddesses/.

Want to learn more?

Person, Place, and Object: Ritual Healing in Roman and Late Antique Palestine

Osiris Must Die – Understanding the Practice of “Menacing the Gods” in Ancient Egyptian Magic

No One Thought to Ask the Fruits: Revealing Philistines’ Traditions

Post a comment