Jonah and the Human Condition

march 2022 | Vol. 10.3

By Stuart Lasine

Ever since Pope Innocent III introduced the phrase “human condition” (conditio humana) in the 12th century, many writers have attempted to describe the problematic features of existence with which everyone must cope. These include our vulnerability, frailty, ephemerality, lack of control, need to labor and, most of all, our mortality. Few texts highlight these features as well as Jonah.

It would be difficult to deny the role played by these sobering realities in human life; in fact, our awareness of our mortality is itself a key aspect of our condition, although we may work hard to obscure that awareness. All these aspects of the human condition are acknowledged in the Hebrew Bible, as well as in writings from ancient Greek and Near Eastern literature.

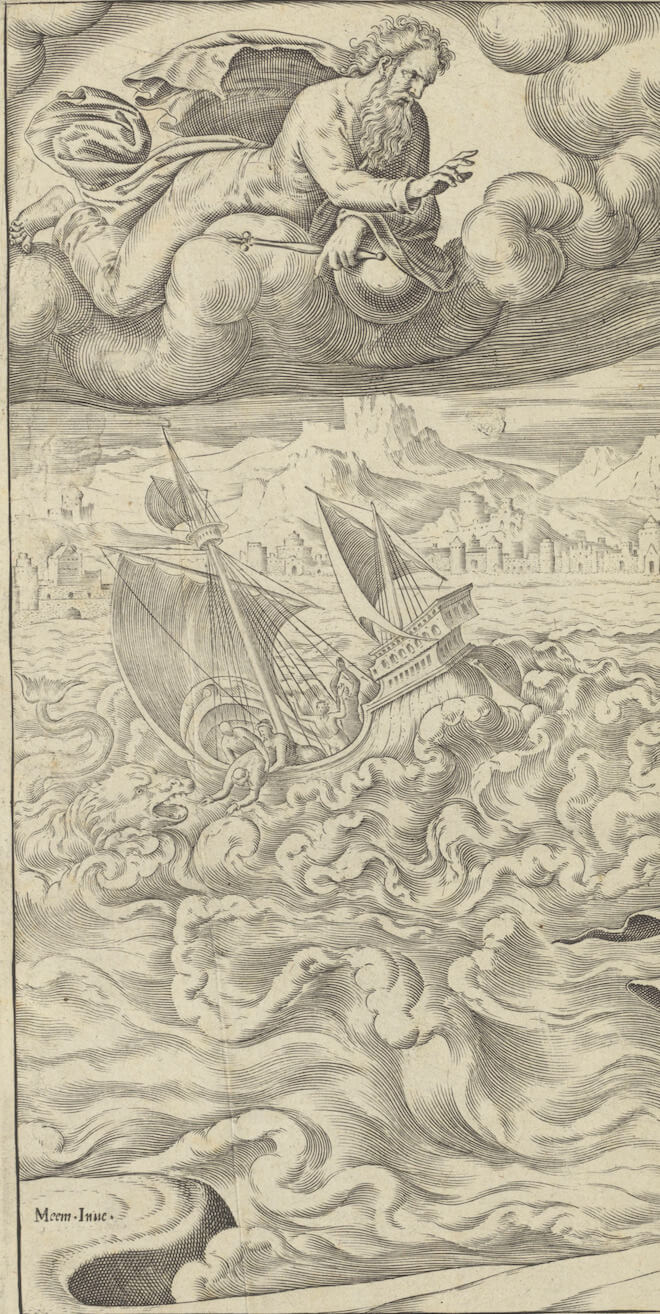

The device of Philips van Marnix van St. Aldegonde, detail from Portrait of Philips van Marnix Heer van Sint Aldegonde (1540–1598) by Jacques de Gheyn, II. 1599. (detail). Public Domain.

Over the centuries the human condition has also been likened to a perilous sea voyage. Figure 1 is a device designed by the 16th century Calvinist politician and writer Philips van Marnix. Figure 2 is a depiction of the popular “Jonah cast over the side” motif by the 16th century painter Maarten van Heemskerck. Both drawings feature a three-masted ship on a turbulent sea, accompanied by a curly-tailed sea monster and a rocky shore nearby.

In both pictures Yahweh is shown in the skies above. One way in which Marnix signals God’s guiding presence is by writing the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) in Hebrew letters above the scene. Around the border of his drawing is his French motto “repos ailleurs”—rest elsewhere. In Heemskerck’s rendering of the Jonah story, God’s body is depicted larger than the ship below. While Jonah is being cast overboard during the storm in Heemskerck’s drawing, Marnix’s device does not include a corresponding figure. Here it is all humans who are potentially under threat of being shipwrecked and cast away.

In effect, Marnix’s drawing presents the human lifespan as a dangerous voyage through space and time. Heemskerck’s image suggests that the story of Jonah may do so as well. In both cases, the biblical God is an essential component of the human condition. Marnix’s point is that we can successfully navigate through the choppy waters of our storm-filled world only if we take scripture—and especially the “reliable Pole Star of the Gospel”—as our guide. Then we will be rewarded with rest elsewhere, that is, in the afterlife.

Maarten van Heemskerck, Jonah Fleeing from the Presence of the Lord to Joppa. 1566 (detail). Public Domain.

But what if our only guide is the Hebrew Bible? Can readers of Hebrew scripture ensure their safety from metaphorical shipwreck if they rely on Yahweh as their navigational guide in the sense illustrated by Marnix? Has Yahweh equipped his human creatures to cope with their brief existence in his dangerous and threatening world? Can we at least count on Yahweh to provide a lifeboat or “big fish” to save those who are cast over the side during our life-voyage?

Given how little readers are told about Jonah’s thoughts, emotions, and motivations, Jonah might seem to be a surprising choice for a case study on the human condition, especially because the book does not include the kind of generalizations on human existence found in Ecclesiastes or Job. Nevertheless, a number of commentators view the prophet Jonah as an “Everyman,” although they disagree about Jonah’s character and therefore about his similarity to themselves. Some view Jonah as suffering from various psychological problems; a few have used the term “Jonah complex” to describe aspects of Jonah’s behavior. However, the book does not furnish us with sufficient data about Jonah’s thoughts, emotions, and motivations to support any definitive psychological profile of the prophet.

It is the plot of the book that evokes essential aspects of the human condition, not the protagonist’s character. Commentators who judge Jonah to be risk-averse, childish, and/or pathological typically point to his flight to Tarshish or his stay in the belly of the big fish. While these plot elements do not provide a basis for any definitive judgments about Jonah’s character, they do evoke human basic vulnerabilities and fears affecting both children and adults. For a developing child, a threat to the integrity of one’s self or identity can lead to (at least symbolic) flight, in order to avoid annihilation or self-dissolution at the hands of an ambivalent or hostile parent. Inadequate parental protection can also prompt a child to experience a mortal fear of being swallowed and eaten up.

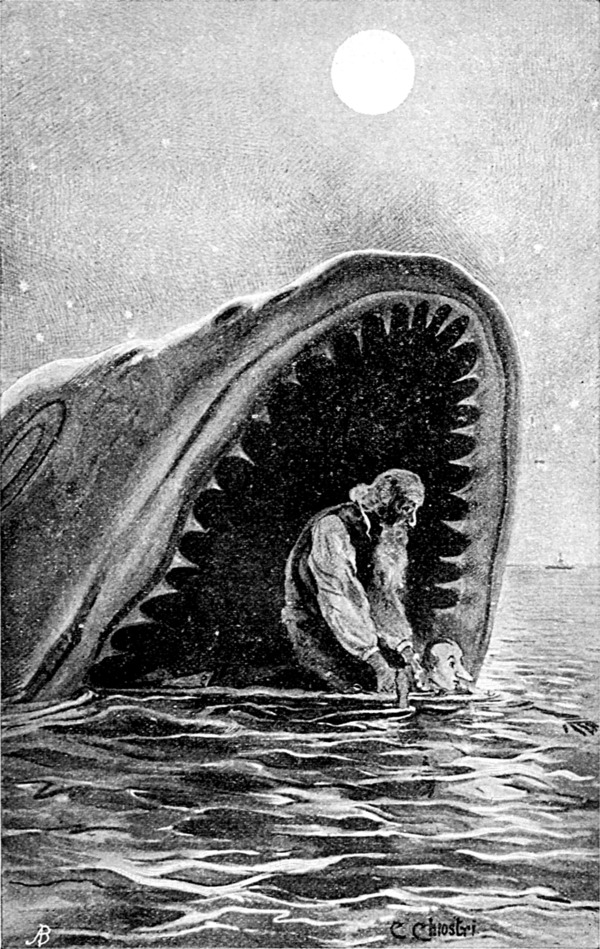

These fears are reflected in a number of fairy tales. In some, the threatening parent is represented by a monster. In others, the parental figure remains idealized, while the threatening qualities are displaced onto the monster. Characters such as Pinocchio and Little Red Cap are swallowed by a monster, yet both remain alive and conscious in the beast’s belly, as does Jonah in the great fish. Here engulfment refers to living entombment rather than to annihilation or nurtured growth in the womb.

This plot is also found in hero stories, the most famous of which is probably the Greek Heracles and Hesione myth, first compared to Jonah in the 5th century CE. The most striking differences between the Heracles story and these fairy tales are that the hero intentionally has himself swallowed in order to destroy the sea-monster from within. Heracles does not need a parental helper to extricate him from the monster. This myth offers a fantasy of adult autonomy, rather than infantile dependence. The big fish that swallows Jonah differs from all such monsters, because it serves a salvific function. Rather than threaten the prophet, the fish preserves Jonah unharmed and deposits him on the shore after Yahweh speaks to it.

If one accepts the common view that Jonah acts childish in the book, his actions can be interpreted as a struggle for power and control. A parent who demands submission and mirroring from the child might read the book of Jonah as teaching that a child must unquestioningly submit to the parent’s demands, not least because resistance is futile. When the final chapter of the book is viewed from this perspective, Yahweh resembles a father who is patiently leading his pouting child toward the recognition that the father’s course of action is correct and that the “child’s” anger and sense of moral outrage are inappropriate.

Jonah Complaining Under the Gourd. After Maarten van Heemskerck. 1566. Public Domain.

Control is also a key factor if one views Jonah as a mature adult who is attempting to keep his integrity. One scholar notes that “with respect to power, God is the one who is in full control of Jonah.” Yet Jonah is able to flee his mission. Admittedly, this merely grants Jonah temporary and ultimately illusory control over his actions. However, his risky flight may also express a refusal to let God’s command control his behavior, even if his refusal results in his annihilation or being entombed alive. On the ship, Jonah controls what the sailors do with him, once he has told them that he had fled from Yahweh. The book’s final chapter shows that the prophet’s resistance to God’s authority remains even after he has completed his mission. His resistance stems from moral objections to the sparing of Nineveh, while his twice-repeated request to die expresses both the futility of this resistance and a desire to control when and how he will escape his untenable situation.

From this perspective, Yahweh may appear to be patronizing to his prophet in the book’s final chapter, rather than being an example of paternal nurturance. God exposes Jonah to the elements as a way of showing him that he cannot make it through God’s world on his own. In this scenario, God is talking down to Jonah and toying with his emotions in a way that makes Jonah appear infantile. Readers who view Jonah as childish do not have to take seriously the prophet’s complaint about Yahweh’s excessive compassion or his repeated death wish.

We leave Jonah still exposed to the elements. We are not told whether he ventured an answer to God’s closing question about pity for the Ninevites and their cattle. The book offers readers no closure. Nor does the character Jonah illustrate all aspects of the human condition in Yahweh’s world, because readers are given no information about the prophet in key areas of human life. For example, we have no way of knowing whether Jonah has a wife and children, let alone whether he is in a position to enjoy life with them in the way recommended by Ecclesiastes or the divine alewife Siduri in Gilgamesh. And we are not told that Jonah values the symbolic immortality offered by fame or reputation, even though it is often assumed that Jonah is angry that his reputation as a true prophet will suffer if Nineveh is not destroyed. What the plot of Jonah does illustrate is the continual and crucial role played by Yahweh in this individual’s life—and the lives of all those addressed by the biblical text.

Stuart Lasine is Professor Emeritus, Program in Religion, Wichita State University.

How to cite this article

Lasine, S. 2022. “Jonah and the Human Condition.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.3. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/lasine-jonah-condition/.

Want to learn more?

Jewish Experiences in the Roman Bathhouses of Judaea/Syria Palaestina

Post a comment