Ethnoarchaeology in Cyprus

july 2022 | Vol. 10.7

By Gloria London

Not all archaeologists excavate dead and buried artifacts. Those of us who work among the living are called ethno-archaeologists. We observe people currently carrying out any activity that was done in antiquity, such as knapping razor-sharp stone tools, fermenting food in clay jars, building homes from sun-dried bricks, and more. My focus is pottery making.

Clay pots were the most common container for 10,000 years. They protect their contents better than baskets and wood, that are not airtight, and stone containers that are heavy and cumbersome. However, there is a downside with pottery – it breaks and cracks easily.

Traditional pottery includes anything produced in a pre-modern technology during the past several hundred years. To this day there are only few ways to make pottery. Other than the most recent advances, the techniques of manufacture have changed little over the millennia. Given that traditional potters today coil-build vessels from local clays, they face many of the challenges that confronted their ancient counterparts.

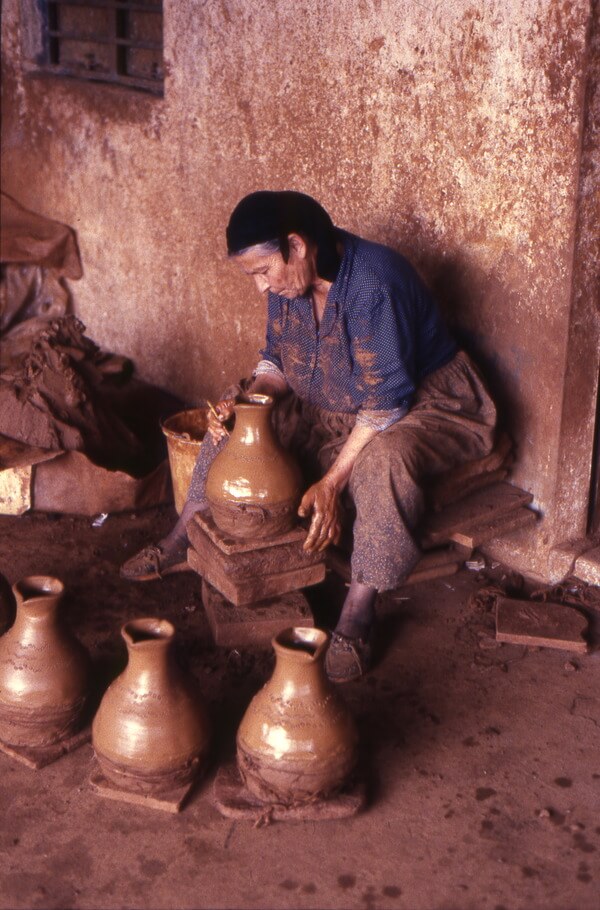

Narrow-necked jugs made in Kornos had incised patterns, two breasts, and three feet. Photo by the Author.

For example, combed, incised, or burnished patterns, rather than paint, persisted on red wares throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages. The ancient patterns are identical to those on pots made in a handful of villages on the island of Cyprus to this day. Coincidence? Continuity? Neither. It is the nature of rocks, clay, and fire. And it is a process that has been handed down from generation to generation.

Salts and tiny rocks endemic to many red clay deposits of the eastern Mediterranean created highly durable and transport-worthy containers. Often, their surfaces were unable to absorb paint due to the abundant, nearly invisible rocks that form the infrastructure of the pot wall. The rocks, unlike the clay, do not absorb paint.

In addition, as pots dried, salts in the clay migrated to the surface and created an impenetrable layer that resisted paint adherence. Even if the uppermost layer of clay containing most of the salt deposit was removed prior to painting, the remaining salt masked the paint and resulted in faded hues when fired. Instead of paint, the easiest decoration involved cutting into the clay, or rubbing to burnish the surface, rather than painting it. Ancient craftspeople encountered the problem of painting that they repeatedly solved with incised design motifs.

On a series of jugs, Paraskavi at the Kornos Pottery Cooperative decorated a jug using a spliced bamboo stalk prior to attaching a handle. Bases later were scraped into a rounded form. June 1986. Photo by the Author.

Painted pottery, especially light-colored wares made in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean, found customers from ancient Egypt to Syria, wherever the local pots had plain red surfaces.

Today, rural women in Cyprus still shape traditional red wares by hand for six months a year. They use the coiling technique, i.e., rolling a coil of clay between their hands, before adding it to build cooking pots, jugs, jars, ovens, juglets, beehives, goat-milking pots, and incense burners.

The coiling technique is a method of manufacture used since the Neolithic Era for vessels of all sizes and shapes. Coils can be long or short, wide or narrow, and applied to pots standing on a turntable or on the ground. Until recently, the rural Cypriots, like their ancient brothers and sisters, fired their finished pieces in wood-burning kilns made of stone.

Sisters Rodou and Elpiniki posed in front of their top-loading kiln as a small fire burned in front of the firebox in Agios Demetrios. August 1986. Photo by the Author.

In 1986 I began a long-term ethno-archaeological study of female potters in Cyprus to record the industry. While living full-time in two different villages for six months, I continuously observed potters at work. At sunrise I awoke to the sound of people pounding clay. At 5:00 AM I saw kilns stacked with raw pots. Shortly afterwards, the potter or her husband ignited a small fire outside the kiln – not in the firebox. The initial flame dried the kiln, pots, and wood. After several hours, the fire was pushed into the firebox and fed with branches. Large logs, added around 7:00 PM, created a roaring fire for two hours. The kiln firing lasted 13-14 hours. The sizzling hot pots were unloaded early the next morning.

I rarely asked questions or offered comments. My inability to speak Greek made it effortless to remain silent and allow the work to proceed largely uninterrupted. I recorded, photographed, and filmed the women with their permission. While professional ethics at the time stipulated that, as researchers, we do not mention people by name, the women I observed entreated me to preserve their names for posterity. It disturbed me that I was not able to give them the acknowledgement they deserved. In 2008, with changes in the prevailing attitudes within the scientific community, I began to reveal their names.

It was uncomfortable to watch, without offering my assistance, as the women crushed the clay and carried heavy pots. All shapes started from a cylindrical piece of clay positioned on a piece of bark or wood placed on a turntable. Women shaped jugs, cooking pots, and all small shapes while seated. After forming the body, each piece dried slightly on the ground before it was ready for the next stage of work on the turntable. Jars and ovens were too heavy to place back on the turntable.

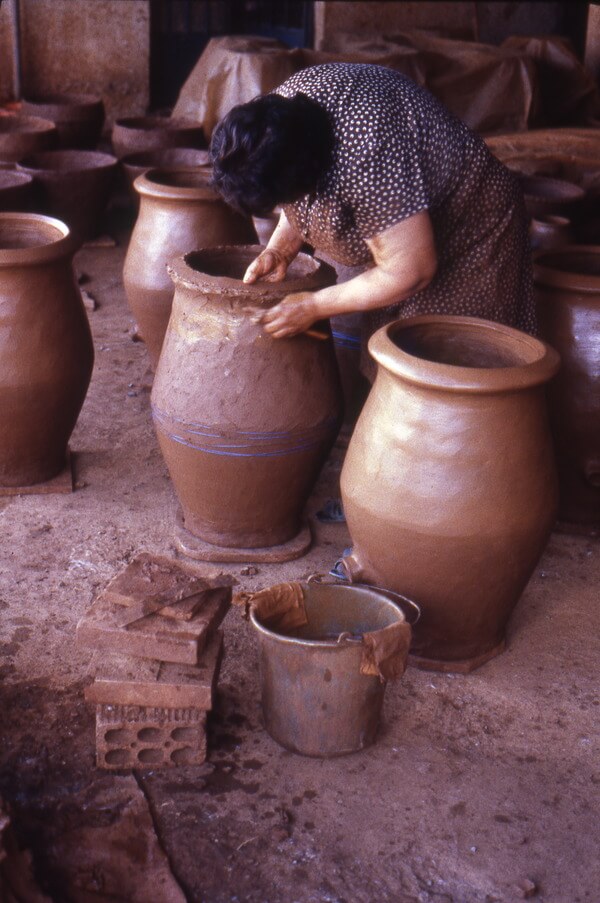

At the Kornos Pottery Cooperative workspace, Eleni Alecou walked around an oven to form a rim from the last coil. Blue yarn encircling the lower body constrict the wet clay. Nearly finished ovens without yarn had a small spout-like flue. June 1986. Photo by the Author.

Instead, women bent over while walking backwards around each pot to add coils. Their vertebrae cracked one after another as they unfolded their bodies to stand up after walking around one oven or jar after another to add coil after coil.

Potters seemed uneasy with my stopwatch and my counting the rare blemished piece (2% observed in 40 firings) s pulled from the kiln. My infrequent interviews conducted through interpreters investigated family histories, pot usage, cleaning, and former methods of distribution by donkeys and carts.

Cypriot urbanites recall drinking cool, sweet water poured from red clay jugs at their grandparents’ village. With great nostalgia, they describe luscious, slow-cooked meals prepared in clay cookware. They ask me if the village food and water could have tasted so much different and better than meals in the cities. Or was it their imagination?

Happily, I can report that their joyful reminiscences are not idealized versions of the recent past. Their experiences and recollections are authentic. Thirst-quenching water, naturally cooled to the perfect temperature, flowed from the jugs that villagers lugged home from the spring. As improbable as it might seem, handmade water jugs sweeten, cool, and improve water quality without chemicals or an artificial filtration system. The unique properties of unglazed red wares purified the water thanks to their ability to leak or “sweat” their contents. While wheel-thrown white wares made in Cyprus leaked a modest amount, it was not enough to impact the taste or temperature of the water. Foreign visitors in the 19th century advised about the need to place jugs in a deep bowl overnight due to the leakage. It is likely that the need for sweaty pots guaranteed their continued manufacture alongside light-colored plain or painted versions since earliest times. Potters, past and present, used whatever clay was available, but red clay jugs always performed best for water. The less porous white jugs accommodated honey, wine, or other fluids.

With a split bamboo tool, Christinou pulled up the clay to form the neck on a coil-built jug at Agios Demetrios. July 1986. Photo by the Author.

Before modern refrigerators, yogurt machines, ovens, and washing machines, women shaped these same devices from clay. Ceramics proved to be essential for daily rural life. Well into the mid-20th century, with bare hands, the potters produced the basic containers for collecting, processing, preserving, cooking, and storing foods. Women, men, and children mined clay from nearby slopes or fields. Their customers were largely Cypriots. Tourists had little interest in the thick-walled cookware, beehives, ovens, jugs, milking pots, or even the small and friable decorated juglets.

Thirty years after my initial visit, residents of Agios Demetrios (Marathasa) in the Troodos Mountains, have conscientiously assembled pots, and the tools to make them, with the intention of establishing a permanent collection in the village. This year, Kornos village holds its first local pottery event.

The purpose of ethno-archaeological research is to observe and record current practices to better recognize and explain the diversity that archaeologists have detected for ancient material culture. My weariness with the conventional use of pottery for chronological purposes and attributing morphological nuances to different time periods rather than human nature led me to find my own way to study ancient pottery.

Andreas mined clay on a slope leading down to Agios Demetrios village. 1986. Photo by the Author.

Although most people assume that ancient women did not function as craft specialists, capable of producing thousands of highly standardized containers by hand, the Cypriot case study proves otherwise. Female potters who worked as itinerants contradict the notion that travelling potters were always men. Women relocated their nuclear family from the hot humid lowlands to the foothills for two months each summer. Young people would collect clay and fuel. After crushing the clay clods under foot, children trampled the clay powder with water in preparation for use. More than one young person married a local in a foothills village started their own pottery workshop that lasted for one generation only. Their children, who did not grow up in a milieu of potters, chose other work.

Ancient handmade ceramics were associated with cooking, processing, preserving, and stockpiling foods. Current traditional craft specialists provide a constructive resource to create valid templates for how their ancient counterparts may have functioned. My decades of work with excavated sherds led me to approach the traditional potters with specific concerns raised by archaeologists. These include how to recognize production locations, why they evade detection, and what accounts for the dearth of waster piles; how pots are used and how long they last; how to reuse sherds; how the craft was transmitted; why some containers have a maker’s mark; how to differentiate household wares made in two contemporaneous communities; and how to consider the behavioral sources of variation in shapes and surface treatments.

To excavate an ancient site and find broken artifacts, untouched by anyone for thousands of years, is exhilarating. But, to work with whole pots as they are made, fired, used, and reused until they become small unrecognizable pieces that blend into their surroundings, is even more exciting. Recording a part of our cultural heritage before it disappears has been my passion.

How to cite this article:

London, G. 2022. “Ethnoarchaeology in Cyprus.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.7. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/london-ethnoarchaeology-cyprus/.

Want to learn more?

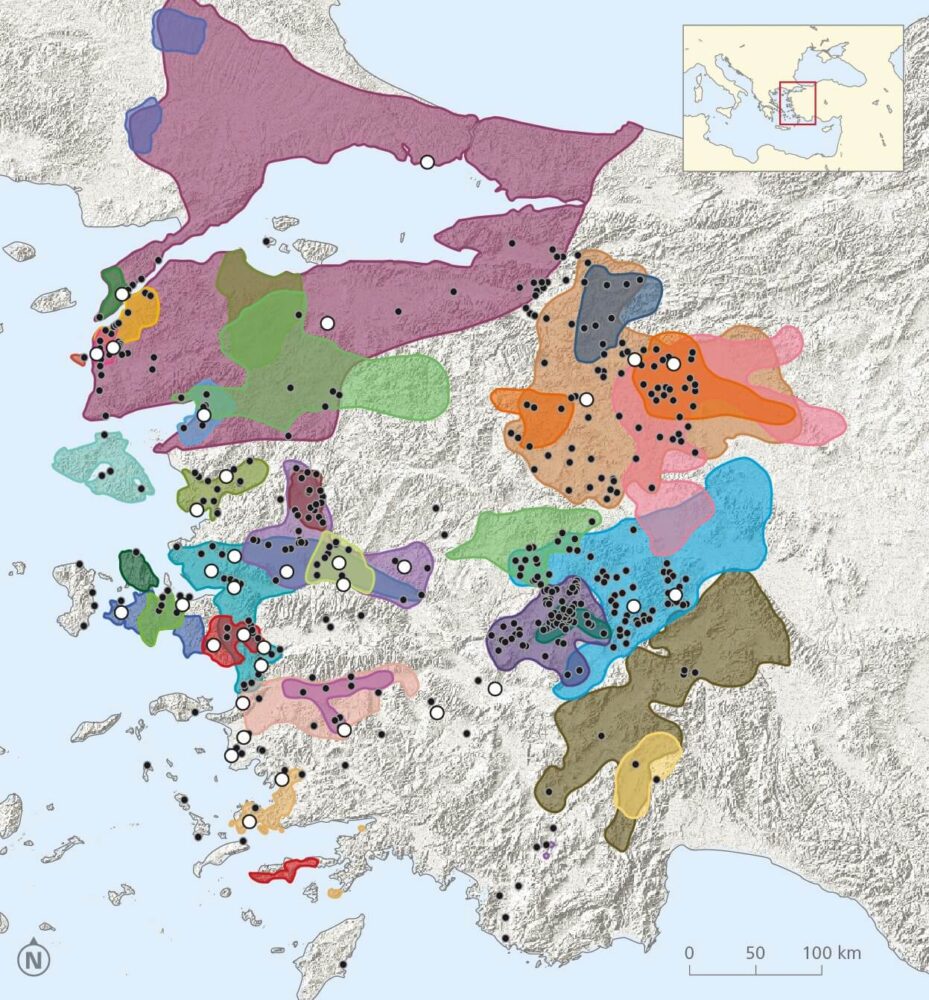

Processing Geospatial Data in Archaeology: Introducing LuwianSiteAtlas for Bronze Age Western Anatolia

The Wheat From the Chaff: What We Can Learn From Studying Plants in Antiquity

Post a comment