Violence of Gender and Gender of Violence in Ancient Egypt

February 2022 | Vol. 10.2

By Uroš Matić

Violence and gender were closely related in ancient Egypt, just as they have been in other past and contemporary societies. Gender systems that imply an asymmetry of power relations between men and women were, among other things, sustained through both physical and symbolic violence.

Ancient Egyptian wisdom and literary texts legitimize the domination of men over women, give advice regarding constraints on women, but also recommend avoiding women who are strangers or women who are adulterous. The 5th Dynasty Maxims of Ptahhotep, for example, counsels:

When you prosper and found your house, and love your wife with ardor,

Fill her belly, clothe her back,

Ointment soothes her body.

Gladden her heart as long as you live,

She is a fertile field for her lord.

Do not contend with her in court,

Keep her from power, restrain her-

Her eye is her storm when she gazes-

Thus will you make her stay in your house.Maxims of Ptahhotep

But the first century BCE Instructions of Ankhsheshonq suggests “Do not take to yourself a woman whose husband is alive, lest he become your enemy.”

Ithyphallic leonine goddess from the temple of Khonsu in Karnak, west wall, room 12, photo, no scale (Courtesy of Asavaa, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Egyptian literary texts depict adulterous women as central figures that disrupt the social order, who end up being punished with a violent death. In one way, such stories served as warnings and regulatory mechanisms; in another, they are prime examples of symbolic violence – “women are to be blamed.” However, juridical texts actually indicate that both men and women committed adultery, but also that both men and women committed violence. Rape, on the other hand, was rarely reported. Evidence from Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt indicates that status played an important role too in shaping gender relations and violence.

Textual sources indicate a general prevalence of violence committed by men against women. But it is hard to investigate to what extent they actually reflect past reality. Physical anthropology comes to the fore here. Analyses of physical evidence of trauma on ancient bones, differences in skeletal markers of occupational stress and health status, actually do indicate lower life expectancy of women than men in ancient Egypt.

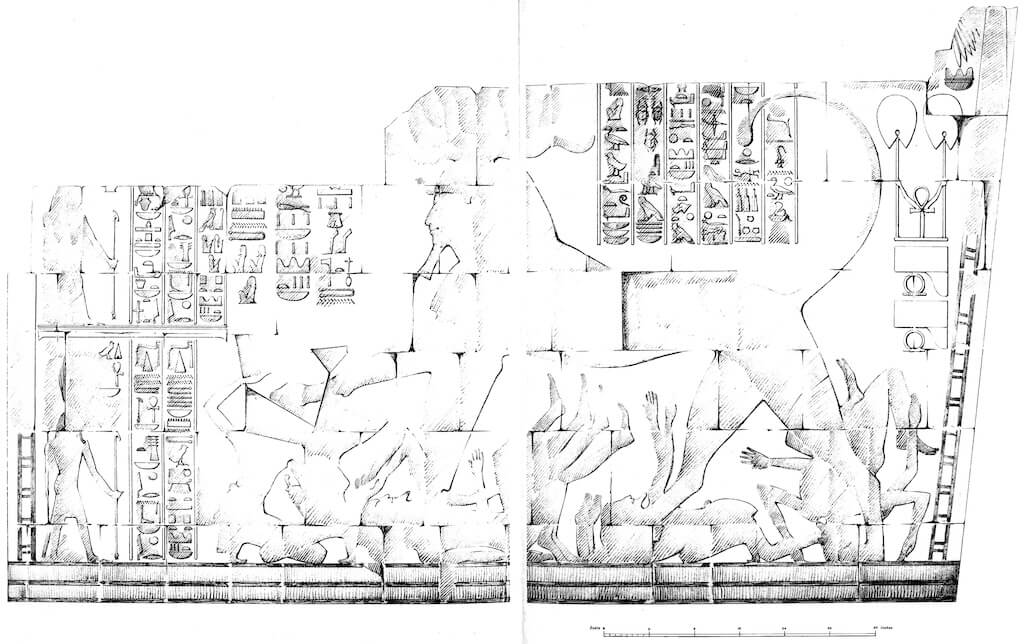

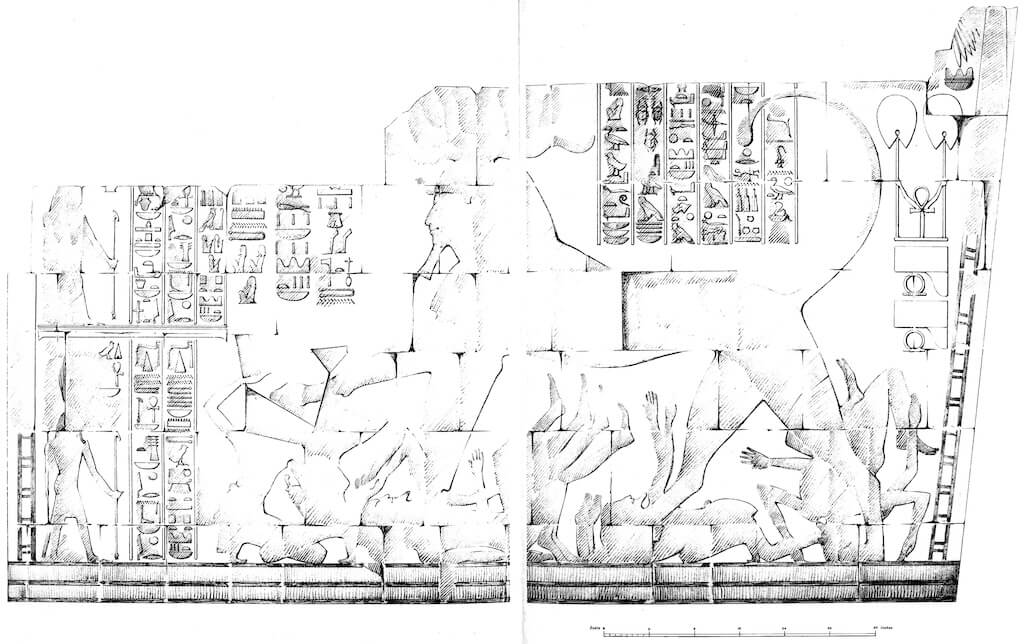

Depiction of the throne of Queen Tiy, showing female captives bound to a sm3 t3.wy (“Union of the Two Lands”) hieroglyph, and the queen, in the form of a female sphinx, trampling female captives. Tomb of Kheruef (TT 192), 18th Dynasty (Detail of line drawing by the author, no scale, courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, after Nims, Charles, Labib Habachi, Edward Wente, and David B. Larkin. 1980. The tomb of Kheruef: Theban Tomb 192. Oriental Institute Publications 102. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: pls. 47 and 49).

Of course, class differences also play a significant role, as skeletal remains of elite women do not show the same patterns as those of women of lower classes. For example, in a study of 271 skeletons from Old Kingdom cemeteries at Giza, the highest incidence of bone fractures occurred in male workers (43.75%), while bone fractures occurred in 20.73% of male high officials. Bone fractures occurred in 26.41% of female workers and 16.66% of female elite. But some of the violence committed against women such as wife-beating and rape, attested in texts, cannot be clearly recognized on the skeletons. In fact, most physical violence does not leave traces on the bones. When such traces are detected, we are actually dealing with the most extreme forms of violence.

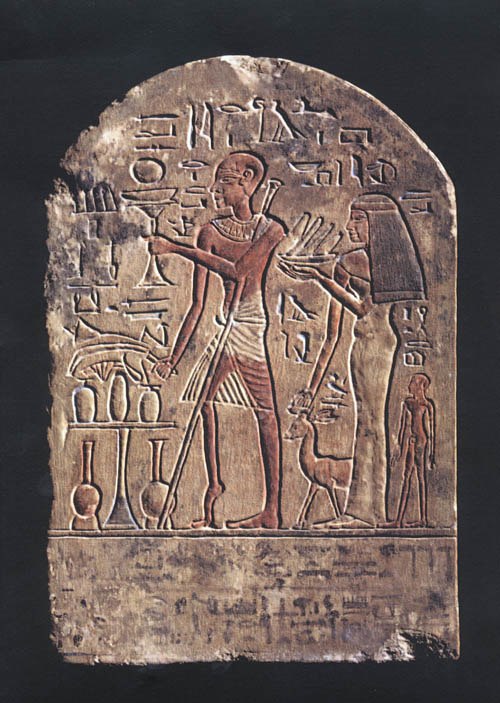

The gender of violence was predominantly masculine, but that does not mean that women did not commit violence; numerous juridical texts refer to women committing different acts of violence. One interesting case for the gender of violence is that of goddesses attested in the context of war providing protection to the king. These goddesses are not only armed with their divine powers, with which they help the king to defeat his enemies as attested in textual sources, but they are also often depicted with an erect penis. Violent goddesses are often described in being both feminine and masculine. Similarly, just as kings smite or trample male enemies, queens smite or trample female enemies. Hatshepsut, a female king, is the only woman depicted smiting or trampling male enemies, but not in the guise of a woman but as a pharaoh (man) or a male sphinx.

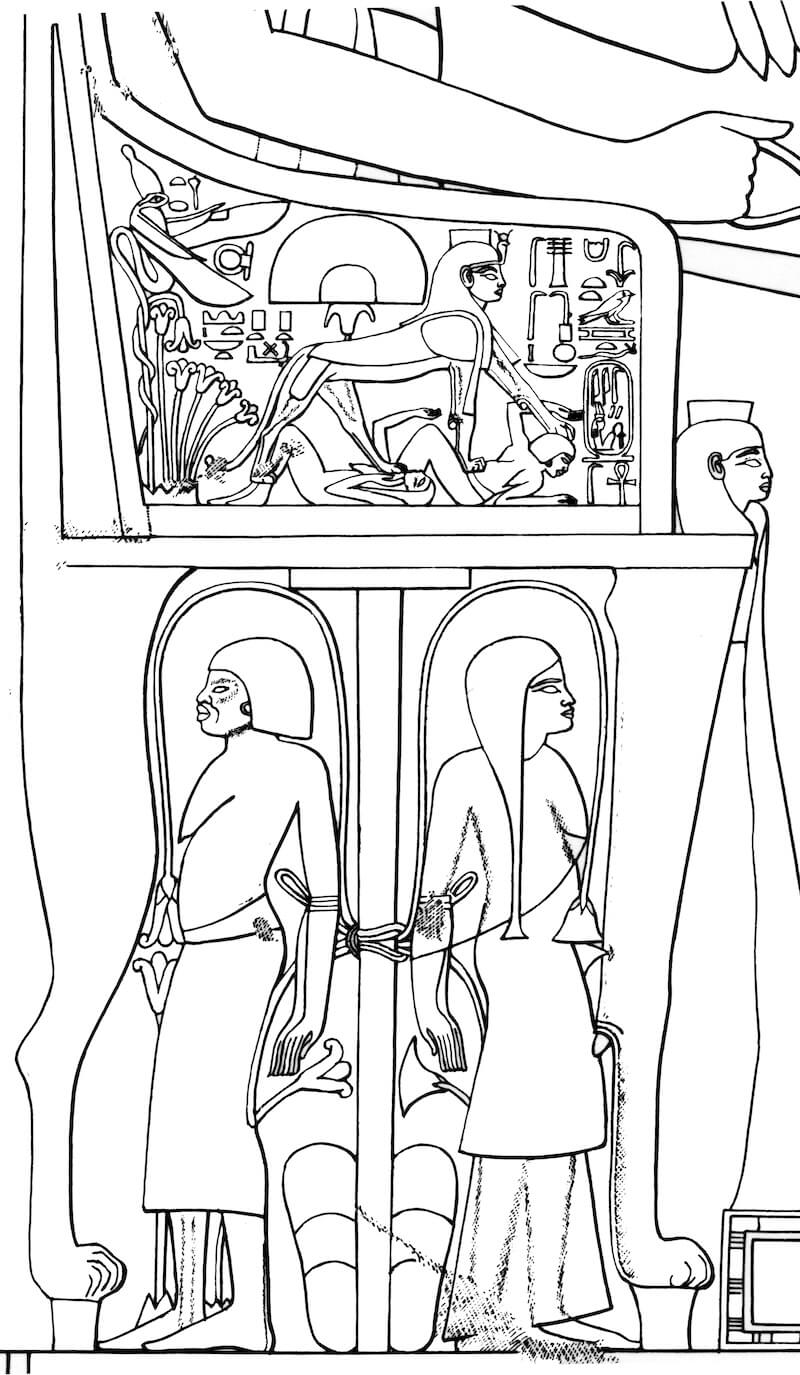

Hatshepsut as a male sphinx trampling enemies, depicted on the south wall of the southern lower portico of her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, 18th Dynasty (Line drawing by the author, no scale, after Naville, Édouard. 1908. The temple of Deir El Bahari VI. Twenty-ninth Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. London: Egypt Exploration Fund: pl. CLX).

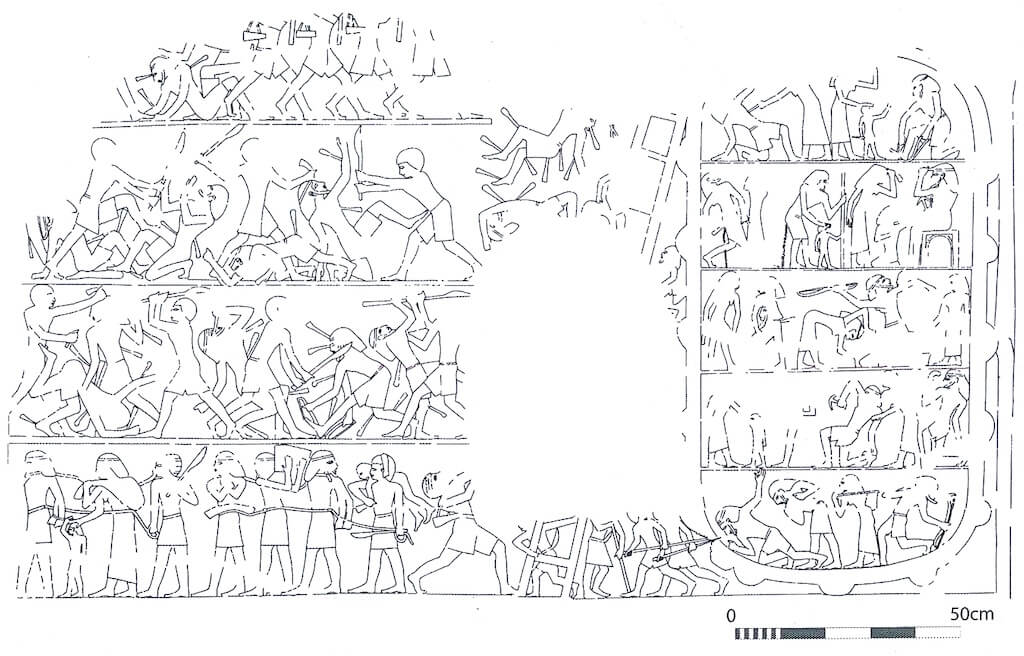

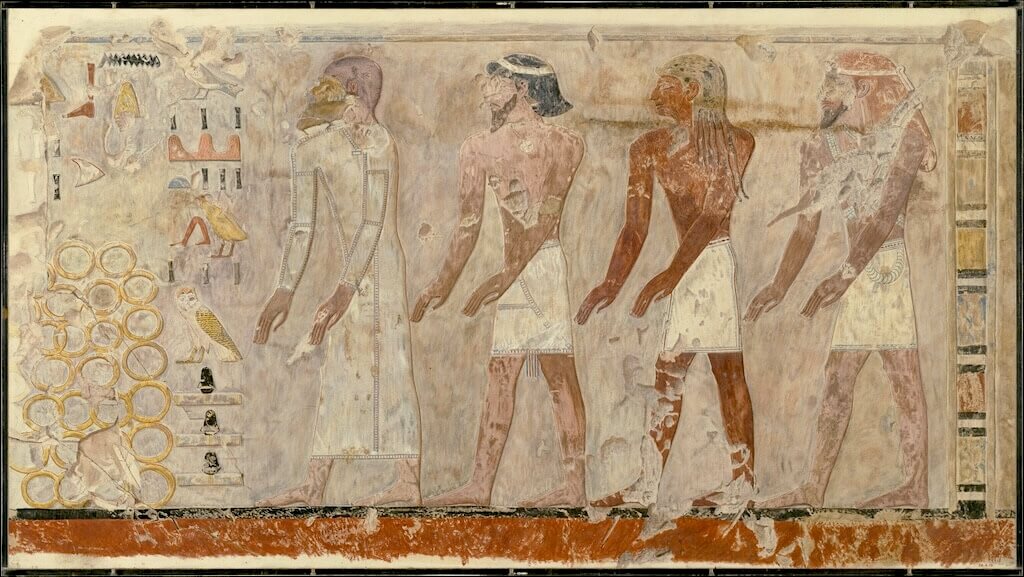

Just as gender relations were sustained through different forms of violence, so were different forms of violence legitimized based on existing power asymmetries of gender. This is especially evident in the discourse of war. Gendered depictions of violence in texts and iconography privileged victorious, active, masculine Egyptian men and downgraded defeated, passive and feminized enemies. For example, already in the Old Kingdom tomb of Inti at Deshasha from the 5th Dynasty we find a scene in which Egyptian soldiers besiege a Syro-Palestinian town whose defenders outside are passive captives. On the contrary, it is the women and children of the town who take action against the intruding Egyptian soldiers by defending the elderly. The underlying message is that this enemies of Egypt are so weak that their men fall on the battlefield while their women and children fight.

The feminization of enemies is observable in numerous texts that compare enemies to women, “harem-women,” (as in the Athribis stele of Merneptah), and widows (as in the Israel stele of Merneptah). In the account of the Second Libyan War, Ramesses III describes the defeated Libyans as having been “made limp” and their leader as “spread out on the ground,” using a sign for a woman giving birth.

From the Old Kingdom, enemies in battle scenes were depicted as passive, defeated, mutilated and incapacitated. This continued throughout ancient Egyptian history, most evidently during the New Kingdom, a period from which numerous battle representations come. For example, the flaccid phalli of Ramesses III’s Libyan enemies are depicted on the Medinet Habu reliefs and phalli of the Libyan enemies were cut off by Egyptians. There is also an indication in the Tale of Two Brothers that the loss of the penis also reflected a symbolic change from masculine to feminine. After being pursued by his brother Anubis on the false accusation that he had committed adultery with his wife, younger brother Bata cuts off his own penis. Later in the story Bata marries, but he warns his wife not to go out alone because he cannot protect her from the sea, since he is a woman like her.

Siege of a Syro-Palestinian fortified town from the tomb of Inti at Deshasha, 5th Dynasty (Line drawing reworked by the author, no scale, after Petrie, William Matthew Flinders. 1898. Deshasheh: 1897. Fifteenth Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. London: Egypt Exploration Society; Kegan Paul; Trench, Trüber & Co.; and Bernard Quaritch: pl. IV).

The hierarchy in which Egyptian soldiers are dominant, contrary to the enemy soldiers that are subordinated, was paired with an asymmetrical power relation of gender. In this way, the dominance of men over women in ancient Egypt served as a metaphor of domination of the Pharaoh and his soldiers over their enemies. Consequently, such pairing of two different hierarchies legitimized both, making the defeat of enemies as normal and natural as the domination of men over women.

A better appreciation of the role of violence in sustaining gender systems and of the role of gender in legitimizing war and violence in ancient Egypt changes our larger perception of ancient Egypt considerably. Although lower classes in ancient Egypt in general did not enjoy the privileged life of the elites, lower class women were affected by inequality even more than lower class men. Similarly, although war affects both men, women and children, among the enemy non-combatants, women are more often the victims of sexual violence than men. Yet from the New Kingdom onward violence against enemy women and children was carefully left out of battle representations, even though it had been occasionally depicted earlier and was still occasionally referred to in the textual sources. Clearly, local Egyptian audiences did not find it appropriate to depict violence against non-combatants on the walls of temples.

Narratives of violence were carefully regulated. They were simultaneously framed by gender through feminization of enemies and by local norms that propagated the protection of widows and children. Consequently, the Pharaoh and his soldiers come forth as ideal men, victorious, masculine and protective. The reality was surely much different.

Uroš Matić is a member of the Austrian Archaeological Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

How to cite this article

Matić, U. 2022. “Violence of Gender and Gender of Violence in Ancient Egypt.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.2. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/matic-gender-violence/.

Want to learn more?

When Is It Ok to Recycle a Coffin? The Rules of the Reuse Game in Ancient Egypt

Osiris Must Die – Understanding the Practice of “Menacing the Gods” in Ancient Egyptian Magic

Post a comment