The Fall of the Bronze Age and the Destruction that Wasn’t

December 2022 | Vol. 10.12

By Jesse Millek

In any telling of the end of the Late Bronze Age (LBA) in the Eastern Mediterranean, there is one key theme that emerges as an integral component of any theory attempting to explain the collapse of the empires ca. 1200 BCE. Destruction. Trade networks were broken apart because the ports of trade were destroyed by earthquakes and pirates. Egypt lost its grasp on the southern Levant because the Sea Peoples destroyed their strong holds. The Hittite empire’s interior was sacked and burned by the Kashka, while its cities and towns on the Mediterranean coast were too destroyed by the Sea Peoples. Indeed, almost every major and many minor sites in the Eastern Mediterranean have been cited as destroyed ca. 1200 BCE as part of a massive destruction horizon.

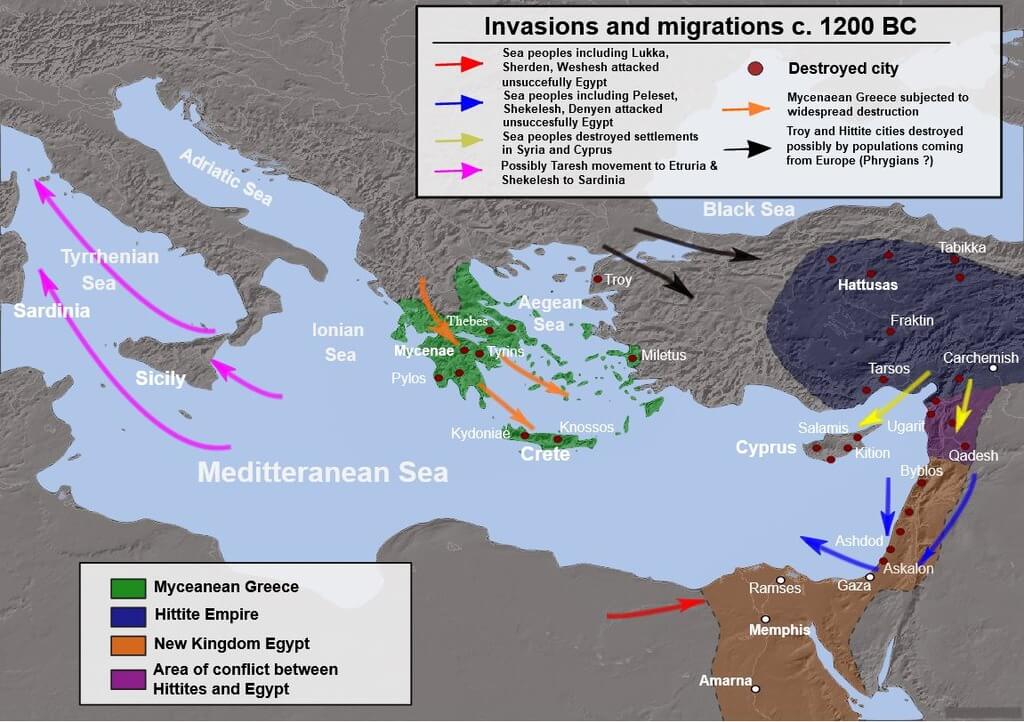

This viewpoint is the most noticeable in the maps of destruction which showcase the breadth and width of the devastation ca. 1200 BCE. The first of these was made by Robert Drews in his 1993 book, The End of the Bronze Age Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. In it, he created a map titled, “The Eastern Mediterranean: Major sites destroyed in the Catastrophe” which featured 47 sites destroyed at the end of the LBA. Drews’s map, and those that have followed, helped to visualize just how many sites were destroyed ca. 1200 BCE, both for the scholar and for the layperson alike. It gave the impression that, wherever one looks in the Eastern Mediterranean, one will find a city of ruins due to the turmoil brought on by the end of the LBA.

“Sites destroyed ca. 1200 BC” (Cline, Eric H. 2014. 1177 B.C The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 110-111 Figure 10).

Yet, what if this wasn’t the case, and Drews’s map was inaccurate, and that over half of all destruction events he claimed affected the Eastern Mediterranean at the end of the LBA never happened at all, or at least not ca. 1200 BCE? As it turns out, this is in fact the case, and Drews’s “Map of the Catastrophe” is a perfect example of how many destructions from this supposed “destruction horizon” were misdated, assumed, or simply invented out of nothing and are what we can call, false destructions.

This first type of false destructions are misdated destructions. Certain destruction events have been put on maps or have been cited as taking place at ca. 1200 BCE, but the destruction occurred either well before or well after 1200 BCE. For instance, Drews asserted that Hazor, in northern Israel, was destroyed around 1200 BCE. Yet, while the site’s LBA monumental structures were indeed burned, this event took place during the first half of the 13th century BCE, well before the end of the LBA. A similar story is true for the site of Miletus on the southwestern coast of Anatolia. While Drews’s put it on the map as destroyed ca. 1200 BCE, the “Third Building Phase” actually dated between 1130-1060 BCE, well after 1200 BCE. Furthermore, it is not even clear if there was a destruction event at the end of the “Third Building Phase” at all.

The map showcasing destruction from the Late Bronze Age collapse page on Wikipedia. Accessed at https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Late_Bronze_Age_collapse (Dec 1, 2022).

The second type of false destructions is the assumed destruction where scholars have assumed a destruction took place based on limited or no evidence. For example, Acco, on Israel’s northern coast, is featured on Drews’s and most other maps of destruction ca. 1200 BCE. Drews even went so far as to claim that a scarab of the Egyptian Queen Twosret, which was found in the ash from Acco’s “destruction,” accurately dated it to around 1190 BCE. The only issue though, is that Drews did not mention that the ash layer was uncovered next to a kiln in an industrial area of the site, and that the ash was refuse from the industrial activity. There is in fact no evidence of destruction at Acco.

For Sinda, which is situated in the hinterlands of Enkomi on Cyprus, incomplete evidence from a limited excavation carried out in a short single season during the 1940s was blown out of proportion into a destruction. Only some ash and some minor signs of burning were uncovered with no clear evidence of destruction such as fallen walls, smashed objects, mudbricks, or more severe evidence of burning. Minor signs of ash and burning can come from any number of mundane sources such as cooking, a hearth, or industrial activities, and there is no clear archaeological evidence that Sinda was destroyed ca. 1200 BCE.

The last type of false destructions is the most pernicious, the false citation. Take for example the site of Alaca Höyük, which is one of the preeminent destructions in Anatolia at the end of the Hittite empire both for Drews and others who came after him. The only problem is that Drews’s evidence for this destruction was a single article written by Kurt Bittel, a famous Anatolian archaeologist, who stated that at least some of the monumental buildings at Alaca Höyük were destroyed by fire based on the finds from the first season of excavations in 1935. However, in the report on the 1935 excavation, the excavator, Arik, never said that he found evidence of an end of the LBA destruction. Moreover, over the last 90 years of excavations, no destruction dating to ca. 1200 BCE has ever been found at Alaca Höyük. The destruction was a scholarly invention not an archaeological reality.

Aerial photo of Tel Hazor. Remains of Iron and Bronze Age cities are seen in the upper tell. Public Domain via Wikipedia.

There is also Kition on Cyprus, which is again one of the featured destruction events from the end of the Late Bronze Age. However, in 1992, the excavator Vassos Karageorghis described the end of the Late Bronze Age as, “At Kition, major rebuilding was carried out in both excavated Areas I and II, but there is no evidence of violent destruction; on the contrary, we observe a cultural continuity.” What is more interesting though, is that the article that this quote appeared in is the same article Drews cited to claim that Kition was destroyed.

So, how bad is the problem? How many false destructions are there at the end of the LBA? If one goes through archaeological literature from the past 150 years, there are 148 sites with 153 destruction events ascribed to the end of the Late Bronze Age ca. 1200 BCE. However, of these, 94, or 61%, have either been misdated, assumed based on little evidence, or simply never happened at all. For Drews’s map, and his subsequent discussion of some other sites which he believed were destroyed ca. 1200 BCE, of the 60 “destructions” 31, or 52%, are false destructions. The complete list of false destructions includes other notable sites such as: Lefkandi, Orchomenos, Athens, Knossos, Alassa, Carchemish, Aleppo, Alalakh, Hama, Qatna, Kadesh, Tell Tweini, Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Beth-Shean, Tell Dier Alla, and many more.

A view of modern Akko. Photo by israeltourism (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Given this rate of false destructions, the question is, just how did it get to be that so many false destructions made their way into the scholarly literature? There is no single answer to this question, however, one of the main reasons for the problem is that up to this point there has been no accepted method of examining, describing, and defining destruction events in the archaeological record. Thus, one archaeologist’s ash next to an industrial installation is another’s massive violent destruction by conflagration. Another problem is the over citation of certain books and articles which themselves have inaccuracies rather than the original excavation reports. The article by Bittel, which began the false destruction of Alaca Höyük, is the go-to article for those discussing destruction in Anatolia at the end of the LBA keeping this false destruction alive. Drews too is a key reference for most discussions of destruction ca. 1200 BCE, and the false destructions he brought into the scholarly world have gone on to become scholarly fact through his repeated citation.

Now, this should not give the impression that there was no destruction at the end of the LBA, as certainly sites like Ugarit, Emar, Hattusa, Mycenae, and Pylos did suffer destruction. However, even here, of the 59 destruction events that did occur ca. 1200 BCE, not all were equal as some were major events while others barely affected the site, but this is a discussion for another time.

Alaca Hoyuk’s Sphinx Gate. Photo by Bernard Gagnon (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Jesse Millek is a Visiting Scholar in the Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte und Vorderasiatische Archäologie at the University of Heidelberg. His new book is Destruction and Its Impact on Ancient Societies at the End of the Bronze Age (Lockwood Press: Georgia).

How to cite this article:

Millek, J. 2022. “The Fall of the Bronze Age and the Destruction that Wasn’t.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.12. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/millek-fall-bronze-age-destruction/.

Want to learn more?

A Failed Coup: The Assassination of Sennacherib and the Assyrian Civil War of 681 BC

The Amorites: Rethinking Approaches to Corporate Identity in Antiquity

Post a comment