Oil, Wine, and People: A Mediterranean Triad

january 2023 | Vol. 11.1

By Catherine E. Pratt

Olive oil and wine are integrated into the daily lives and seasonal rhythms of people living in modern Greece. Perhaps even more striking is that despite dramatic political, social, economic, and environmental changes in recent history, the Greek people have nevertheless maintained connections to their ancestral land and its products, even if they now live in a city. Oil and wine are at the forefront.

More than 30 varieties of wine and many varieties of olive oil have been awarded ‘Protected Designation of Origin’ status by the European Union, along with many other agricultural and food products. Modern Greece defends this connection fiercely: in 2005 the European Court of Justice ruled on a lawsuit brought by Greece that the term feta could only be used in connection with the cheese made in Greece itself. In Greek eyes feta is part of Greece.

This insight led to the consideration of the underlying motivations, both conscious and subconscious, for the maintenance of this incredibly long-lasting connection between people, place, oil, and wine – present and past. Did communities in the pre-Classical period of Greece also maintain this continuity despite enormous external and internal changes? The synthesis of the archaeological, textual, and contextual evidence for the pre-Classical period of Greece presented in my book, Oil, Wine, and the Cultural Economy of Ancient Greece: from the Bronze Age to the Archaic Era suggests that people did indeed develop an inescapable relationship with oil and wine. During this long-term process, oil and wine became what I call “cultural commodities” and remain as such until today.

Pylos feasting equipment, including kylix cups and kraters for mixing wine. Photo by Author.

In the Greek case oil and wine take an active role, shaping ancient Greek culture as they became inextricably bound to humans and humans to them. Ultimately, the cultural commodities of oil and wine become signifiers of Greek cultural identity, deeply rooted in social and ideological practices, rather than mere agricultural products functioning within an economic context.

I define cultural commodities as products that continue to be produced because they have become indispensable for the functioning of social and economic exchanges well beyond economic advantage. The indispensability of cultural commodities is a result of the intersection of dependency and value. That is, a relationship of dependency developed between people and the commodity that was reinforced and held in place over time by a positive network of value. Such commodities were both needed and wanted; they reproduced or symbolized something fundamental about the society itself.

In the Greek case oil and wine take an active role, shaping ancient Greek culture as they became inextricable bound to humans and humans to them. Ultimately, the cultural commodities of oil and wine became signifiers of Greek cultural identity, deeply rooted in social and ideological practices, rather than mere agricultural products functioning within an economic context.

Cretan transport stirrup jar from Mycenae’s House of the Oil Merchant (no. 9099) with multiple seal impressions on clay spout cap. Photo credit: Catherine E. Pratt

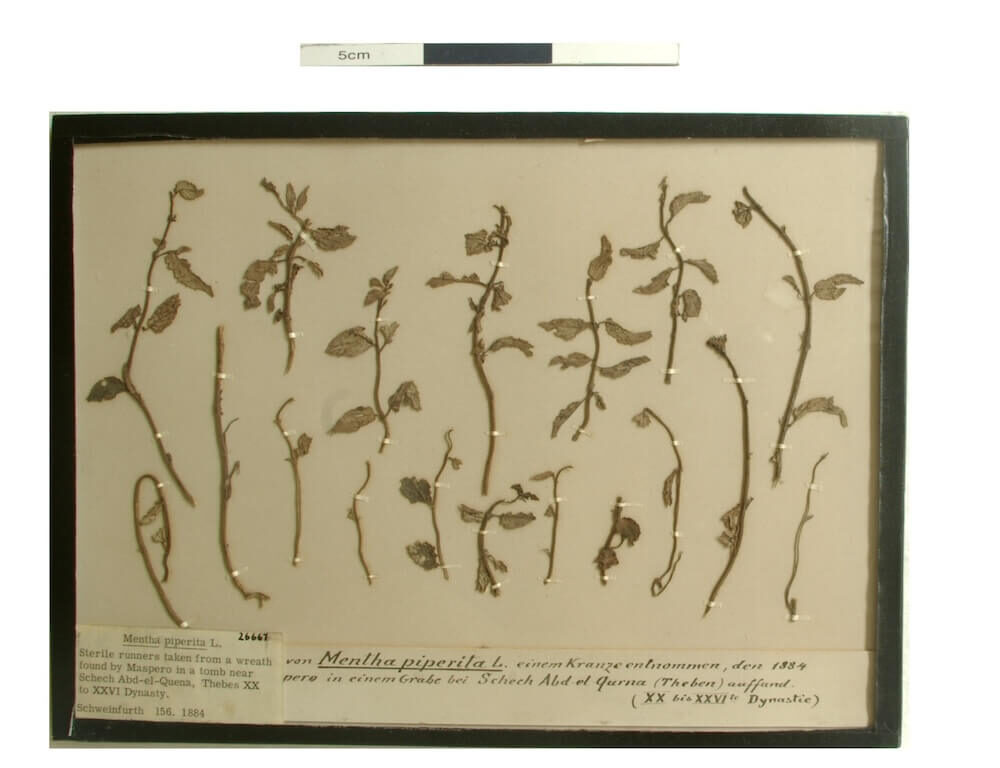

This study is the first to explore how oil and wine became increasingly entangled in Greek culture from the Late Bronze Age to the Archaic period (ca. 800-480 BCE). Using ceramic, architectural, and archaeobotanical data, I argue that Bronze Age exchange practices initiated an inescapable network of dependency between oil/wine and the people who produced, exchanged, and used them.

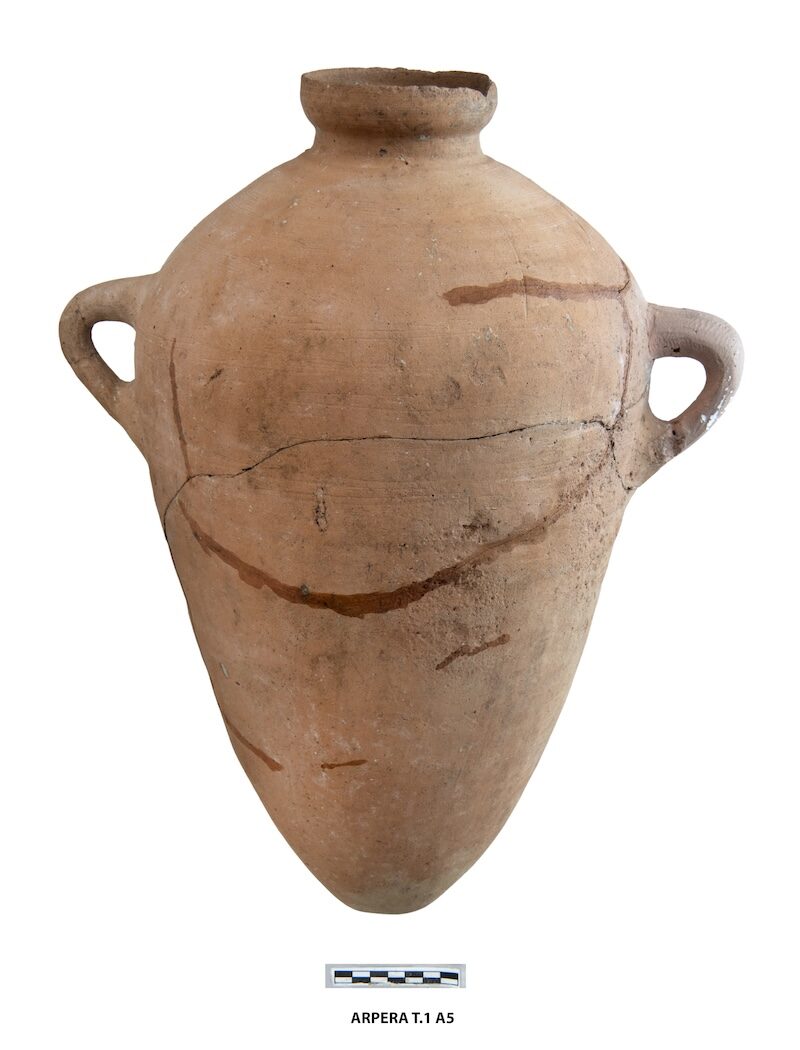

Analysing contexts of production, feasting deposits, and amphoras allows a holistic overview of these exchange practices. After the Late Bronze Age palatial collapse (ca. 1200 BCE), these prehistoric connections intensified during the Iron Age and resulted in the large-scale industries of the Classical period. Iron Age oil and wine exchange is best seen through commensal deposits and amphora movement. The distribution of North Aegean amphoras, decorated with concentric circles and marked post-firing, illuminates the increasingly intricate social and economic networks developing from the 10th to 8th centuries.

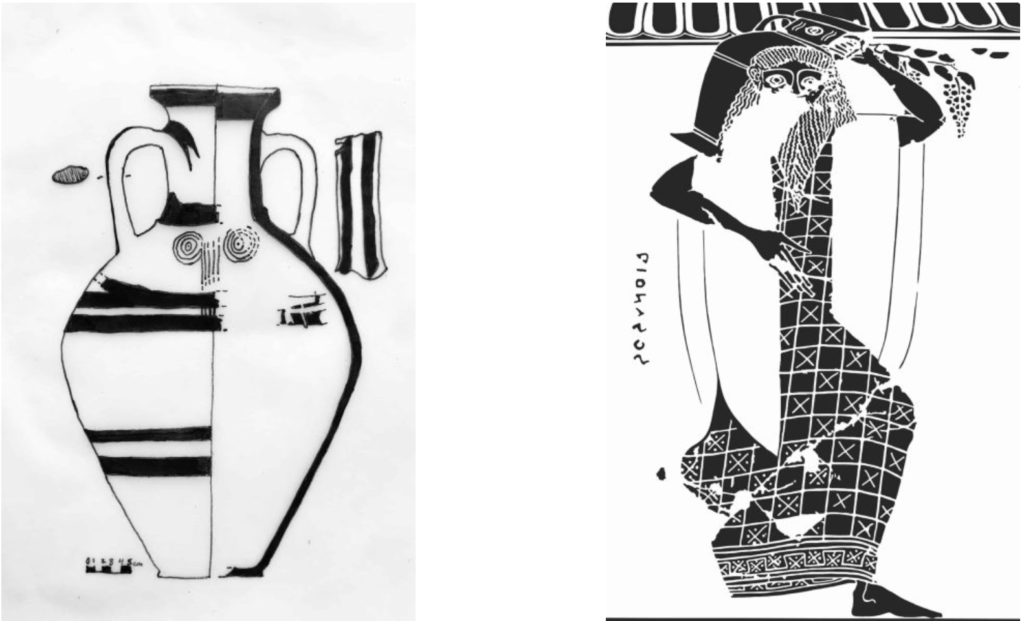

(Left) Early North Aegean amphora from Troy. After Catling 1998, pl. 1:3. Image by author.

(Right) Detail of the François Vase (Museo Archeologico, Florence) with Dionysos carrying an SOS-like amphora on his shoulder. Image by Chelsey Gareau.

The beginning of the Archaic period (end of the 8th century BCE) marks a point when regions like Attica started to specialize in oil and wine production and large-scale export. At this point, the varieties of commensal events, from small-scale private symposia to large-scale communal events sponsored by regional sanctuaries, further entrenches peoples’ dependency on surplus oil and wine. Moreover, so-called Attic SOS amphoras are found all over the Mediterranean Sea and are often the first Greek imports to non-Greek sites. By offering a detailed diachronic account of the changing roles of surplus oil and wine in the economies of pre-classical Greek societies, this book contributes to a broader understanding of the complex interconnections between agriculture, commerce, and culture in the ancient Mediterranean.

The implications of this historical study have a meaningful impact on issues of current and future agricultural practice and commerce in the Mediterranean. By understanding the resiliency of the relationship between people and olive oil/wine over a long period of time, we can gain some general insight into how to maintain these connections through political, economic, and environmental hardship. As the Mediterranean once again enters into a period of dramatic climate change today, it is important to understand more fully the outcomes of these changes in the past and how populations adapted to and, eventually, thrived in new conditions. Indeed, the cultural commodities of olive oil and wine were as much entangled in Greece’s past as they are in Greece’s future.

Catherine E. Pratt is Assistant Professor in the Department of Classical Studies at Western University, in Ontario.

How to cite this article

Pratt, C. 2023. “Oil, Wine, and People: A Mediterranean Triad.” The Ancient Near East Today 11.1. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/pratt-oil-wine-people/.

Want to learn more?

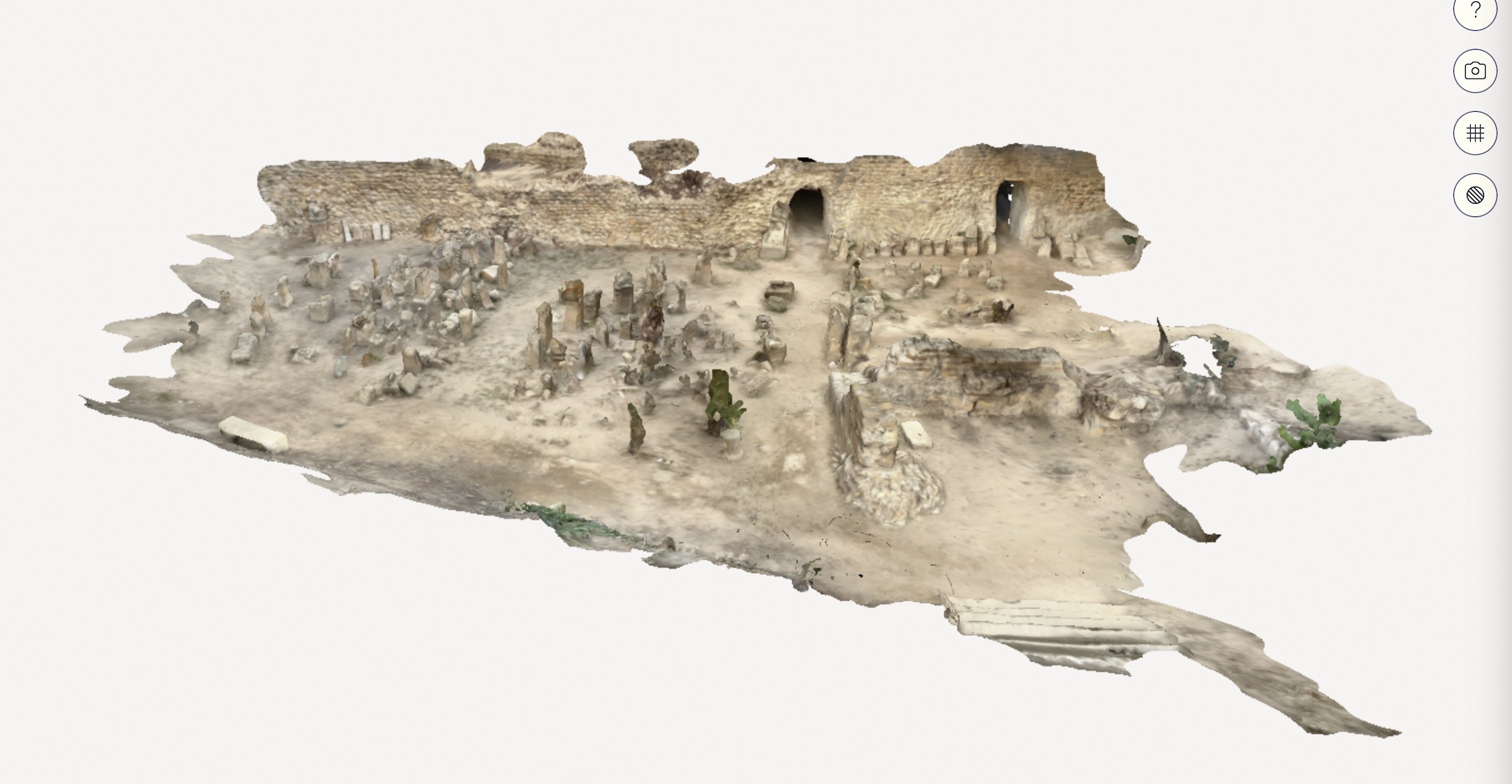

Putting Carthaginian Stelae Back Into Context: The ASOR Punic Project Digital Initiative

Cyprus and Ugarit: A Tale of Two Late Bronze Age Mercantile Polities

Post a comment