The Medico-Magical Squill

January 2022 | Vol. 10.1

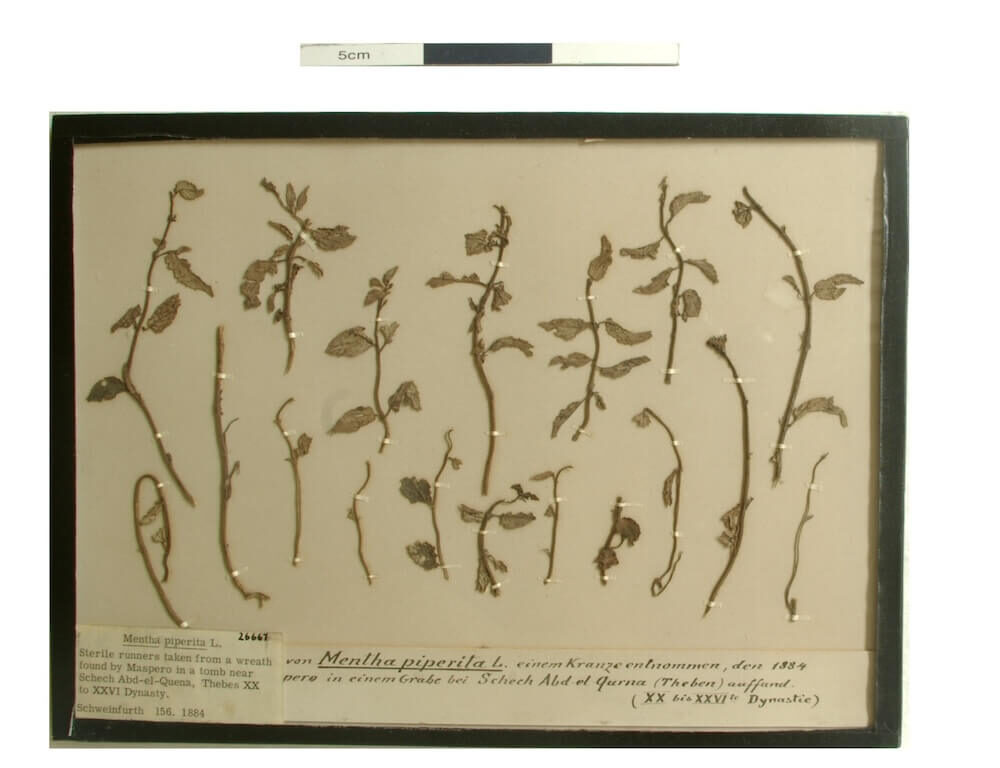

By Maddalena Rumor

Penetrating the deepest meaning of a word allows our brain not only to make sense of the idea it conveys, but also to disentangle related concepts, thus generating an intense sense of pleasure and gratification. When dealing with ancient Babylonian names of plants and drugs, alas, that sense of gratification is rare, but not for lack of material.

On the contrary, ancient Mesopotamian pharmacopoeia was impressively large, with hundreds of substances known by many names, nicknames, and synonyms. Most of that knowledge, however, passed into oblivion after the Akkadian language died out about two millennia ago, leaving us with the empty shells of plant names with inadequate clues as to their meaning. Yet sometimes, helpful suggestions emerge where we least expect them.

This is the case of a plant that the Sumerians called Ú SIKIL, the “pure/purifying plant,” which from the 2nd millennium BCE was known as sikillu in Akkadian. We know little about sikillu: it somehow resembled an onion, it had leaves, a stem, flowers, and was used in healing. It was also particularly good for purification (as per its name) and for witchcraft. How exactly it “purified,” though, remains a mystery.

Sea squill inflorescence. (Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Unexpectedly, Greco-Roman literature comes to rescue. Here the name of a plant is recorded that is very similar to sikillu, Greek skilla, which is normally translated in English as “sea squill” or “sea onion” from its resemblance to the common vegetable (although quite bigger and more toxic, when not deadly).

A careful comparative analysis of the textual evidence suggests that Akkadian sikillu and Greek skilla (or Latin scilla) were just two names referring to the same plant. The analysis is based not only on etymology, but also on physical descriptions of the plant, habitat, healing properties and procedures, both medical and magical.

In short, sikillu and skilla appear in parallel Babylonian and Greco-Roman treatments to cure the same host of ailments (of the abdomen/chest, eyesight, teeth, feet, and even snakebites). It was especially valued as a multi-pronged evacuant (being diuretic, laxative, and emetic) in both cultures, as is evident from the examples below. The first passage is from a Neo-Assyrian (8th-7th c. BCE) medical text:

If ditto (a man’s intestines are continually bloated and swollen up and his stomach continually tries to vomit), have him suck sikillu, its green/yellowish (fleshy part) mixed with lard, on an empty stomach, have him drink sour beer, and he will recover. (BAM 575 ii 19)

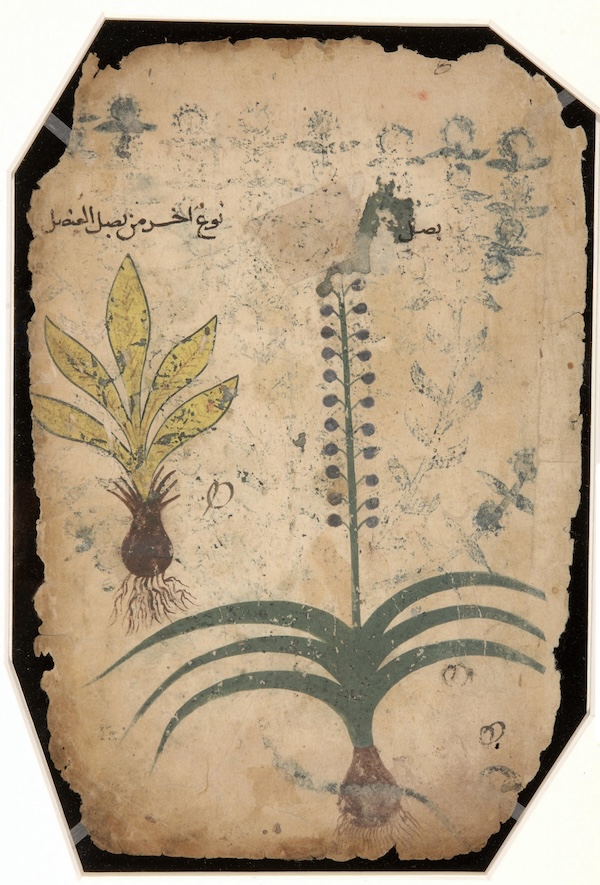

Illustration of Skilla from 13th century Arabic copy of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica. Public Domain

The second, from Roman writer Celsus (1st c. CE):

If there is flatulence (in a dropsical patient) and, owing to that, pain is frequent, a vomit is beneficial (…) it is useful to suck a boiled scilla bulb. (De Medicina III 21.9–10)

Clearly, when a wholesome vomit was prescribed, the squill (Akk. sikillu – Lat. scilla) was the way to go, in Nineveh as well as in Rome.

Now, any new identification is certainly a welcome addition to our knowledge of Babylonian materia medica, but not necessarily exciting. More interesting are the side implications and clarifications, which shed reciprocal light on both Mesopotamian and Classical traditions.

Greek and Latin passages, for instance, can help clarify the meaning of the Sumerian name Ú SIKIL “pure/purifying plant,” which is otherwise inexplicable. As Theophrastus explains, this was a plant that naturally fought off decay and had the power to keep anything pure from the attack of parasites.

“Skilla is tenacious of life (…). It is even able to preserve other things that are stored, for instance the pomegranate, if the stalk of the fruit is set in it.” (Hist. pl. 7.13.4).

Conversely, the evidence from Mesopotamia offers a rationale for some puzzling uses of skilla in early Greek literature (VI-IV c. BCE), where the plant was inexplicably associated with magico-religious cleansing.

From time immemorial, in Mesopotamia, the mechanically “cleansing” (=evacuant) powers of sikillu had been observed to work in the removal of evils that were believed to have a magical cause, being employed, for example, in anti-witchcraft rituals to expel bewitched food and beer (i.e. food poisoning or heartburn) from the body. By analogy with this property, the plant was likewise used in rituals to remove male impotence (or the impurity causing it).

Cross-section of squill; photo courtesy of author

Appreciating this ability of sikillu is key to our interpretation of skilla in early Greek literature. Here the plant is employed in a variety of situations, all incomprehensible for us, and all interpreted as magical, associative, or based on (rather nebulous) ancestral beliefs. In short, nobody understands exactly what the squill was doing there.

In Hippocratic gynaecological recipes, for instance, it was applied as a “cleansing” vaginal suppository to soften and purify the uterus, and prepare it for conception. Not a brilliant idea, as conception was probably the last effect a woman would have experienced! But the use of squill did not stop at vaginal suppositories. It was also considered a cure for madness, which also needed to be expelled from the body by means of purification (how this was done is not specified) [Diphilus, fr. 125 (126)].

Even more curiously, it appears that it was used to beat a pharmakos (an unfortunate fellow, used as a scapegoat) on the genitals, and drive him out of town, together with his city’s misdeeds (Hipponax, fr. 6). Whatever we make of the elements surrounding this cruel practice, the choice of beating someone’s penis with a squill is at the very least perplexing, without saying that a nice wooden club would have probably done the job more effectively – surely it would have been easier to handle.

All these practices, however, suddenly make sense, if we accept the identification of skilla/squill with Akk. sikillu, which suggests they could have developed out of Near Eastern customs involving the use of sikillu to medicinally purify and cleanse the insides of the body mechanically (as an evacuant). Hence, having acquired a reputation as a purifying agent (as the Sumerian name indicates), the squill would have also begun to be applied in a translated, symbolic, or analogic way to dispel more elusive causes of impurity/evils from the body, such as general pollution, moral stains, grief, marginal persons, and the like. Both mechanical and symbolic aspects are attested in the Babylonian tradition, whereas it seems that only the latter were attested in early Greek sources. The perplexing ways skilla was used in early Greece may thus be related to ideas belonging to ancient Near Eastern traditions, even though the rationale behind those ideas had only partially translated.

Sometimes our past preserves memories, or traditions, that strike us as very odd; but throwing light on just one of their elements, in this case the deepest meaning and (cross-cultural) history of a single word, may be just what we needed to reconnect several pieces of the puzzle.

Maddalena Rumor is Assistant Professor and ACLS Fellow 2020-2021 in the Department of Classics, at Case Western Reserve University.

Further reading:

Patera, M. (2019): “Les usages rituels d’une plante médicinale: à propos de la scille.” In A. Gartziou-Tatti and A. Zographou (eds.), Des dieux et des plantes. Kernos 34, 201–220.

Rumor, M. (2020): “Akkadian Sikillu and Greek Σκíλλα in their Medical and Magico-Ritual Contexts.” In J. C. Johnson (ed.) Patients and Performative Identities: At the Intersection of the Mesopotamian Technical Disciplines and Their Clients (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns), 169–192.

Stol, M. (1987): “Garlic, Onion, Leek.” BSA 3, 57–80

How to cite this article:

Rumor, M. 2022. “The Medico-Magical Squill.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.1. Accessed at: http://www.anetoday.org/rumor-squill-medicine/.

Post a comment