What’s in a Name? Warriors and Warrior Burials in the Near East

MAY 2022 | Vol. 10.5

By Chris Stantis

The dead, much like the living, don’t fit easily into convenient labels.

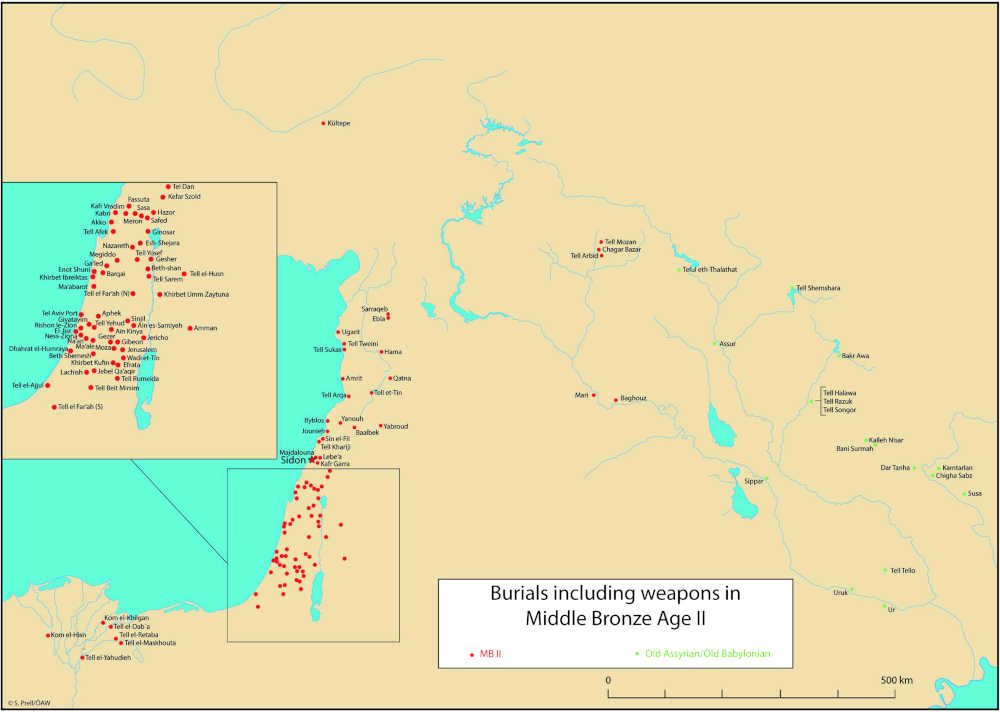

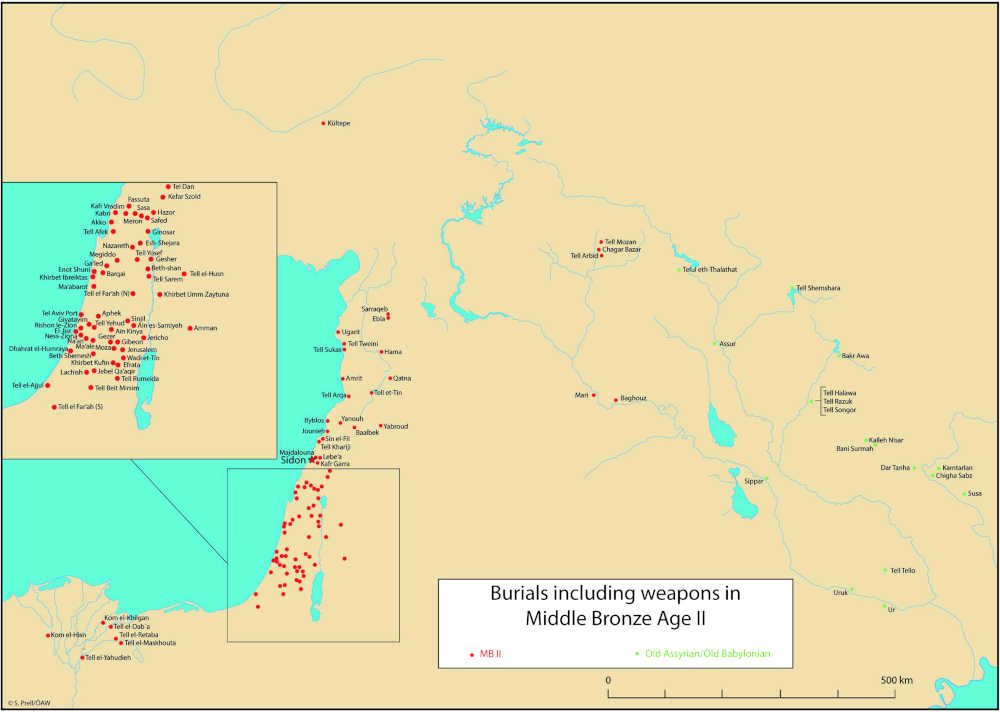

In the 1980s, the term “warrior graves” was coined to describe elite tombs with bronze weaponry found in the ancient Near East. This funerary practice can be traced for the first time to the beginning of the Early Bronze age (ca. 3200 BCE) in Northern Mesopotamia, spreading further south and reaching the Eastern Nile Delta of Egypt by the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1600 BCE).

There the Middle Bronze Age “warriors” were sometimes identified as the Hyksos, allegedly bellicose invaders of Egypt who ruled for a century before being violently expelled. Now, however, we understand Hyksos as something else, a series of Egypto-Canaanite dynasties that emerged only after many hundreds of years of cultural interaction and hybridization during a period of local Egyptian fragmentation.

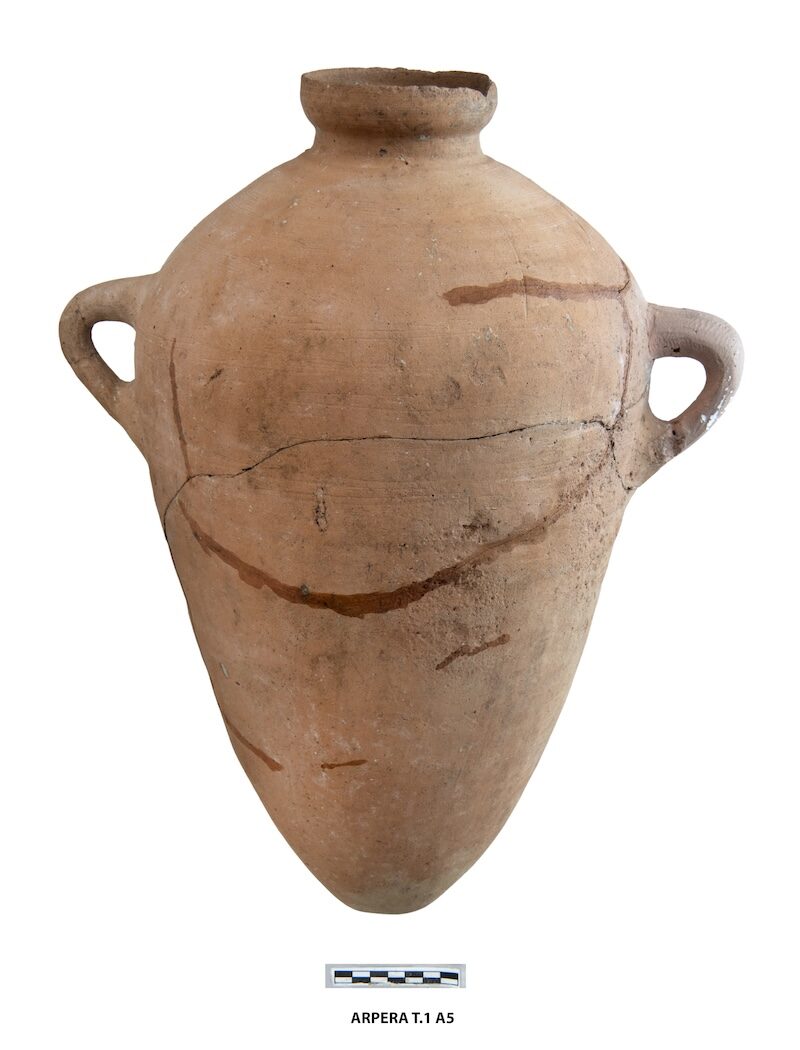

So called “warrior burials” are defined by certain traits, such as burial items of copper alloy weaponry (whether axes, daggers, swords, and/or javelins). All, with few exceptions, contain single inhumations (only one person rather than multiple people) in tombs constructed of stone or mudbrick. There are often also other grave goods that are costly and precious, beyond the weapons: imported ceramics, jewelry, seals and scarab amulets. These burials paint a picture of an elite with disposable wealth, who could afford to put all of these precious objects in a tomb. While other burials might have some of these grave goods, tombs with bronze weapons were set apart from others of high social status.

Burials including weapons in Middle Bronze Age II in the Levant and the Nile Delta. © Dr S. Prell

But were these the tombs of warriors?

In a recent paper, my friends and I looked at the “warrior burials” of Sidon, on the coast of modern Lebanon. This site contains a Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000-1600 BCE) cemetery of over 114 burials, with six burials showing the classic grave style and burial accoutrements typical of a warrior burial.

Bioarchaeologists have a unique set of skills useful for reconstructing how people lived in the past. With keen eyes, calipers, and some chemistry know-how, we can investigate trauma (e.g., were these “warriors” actually in fights?), diet, and occupational activity as well as other lines of evidence in the human skeleton.

Panorama of Sidon as seen from the top of the Sea Castle, 2009. Image by Peripitus, used under CC-BY-SA-3.0.

But at Sidon, even basic demographic information suggested the burials represented something other than an elite fighting force. While four of the six warrior burials were identified as adult males, two were children. One was a teenager and the other, buried with a narrow-bladed dagger of bronze and silver, was about five years old at death. Not exactly a seasoned fighter.

Other bioarchaeological information also suggested these “warriors” lived lives no different from the common population. There was no evidence of martial occupation or interpersonal violence on their skeletons, no evidence of hard work resulting in arthritis or other debilitating diseases. The only difference we saw was fewer carious lesions (e.g., “cavities”) in this group compared to the general population, which may imply better dental care for elites.

At the end of the day, we suggest the term “weapons-associated burials”—admittedly a mouthful—is a better assignation than “warrior burials.” It’s not that the idealization of warriors and warrior culture wasn’t given to these individuals within their culture: the precious bronze weaponry placed next to them indicates they were given the mantle of a wealthy male with martial prowess. Here, there is a specific intersection of a masculine ideal and the wealth necessary to place precious bronze within a tomb rather than re-use and re-cast. With it, the notion of warriors and violence in Middle Bronze Age society should be reevaluated.

But as we’re not people from that Middle Bronze Age culture, it can be easy to assign our own unconscious expectations about “warriors” and misinterpret the evidence. As with our understanding of the Hyksos, it is easy to generate specific interpretations on the basis of limited data; in one case later propagandistic Egyptian accounts, in another, a sort of modern (or perhaps Medieval) association of weapons with masculinity, who become specialists in violence. But the data from Sidon suggest that weapons were a sign of wealth and perhaps social class, with a vocational specialty violence at best being implicit or aspirational.

Archaeologists should be careful with terminology, and we need to keep challenging ourselves and fight the urge to be — quite frankly — lazy with our language. Without too much thought, weapons-associated burials become warrior burials become warriors. Even if it’s not archaeologists guilty of sloppy language (and we can be), thoughts can be misconstrued when speaking to the public. Everyone needs to be careful with their language and how it might be (mis-) construed. Fortunately, more in-depth analyses, in this case of bones, have the potential to correct both our interpretations and our language.

Chris Stantis is currently a Peter Buck Postdoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Follow her on Twitter @ChrisStantis.

Further Reading:

Kharobi, A., Stantis, C., Maaranen, N., & Schutkowski, H. (2021). Once were warriors: Challenging occupation preconceptions in Lebanese weapon-associated burials (Middle Bronze Age, Sidon). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3027.

Moen, M. (2019). Gender and Archaeology: Where Are We Now? Archaeologies, 15(2), 206–226.

How to cite this article

Stantis, C. 2022. “What’s in a Name? Warriors and Warrior Burials in the Near East.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.5. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/stantis-burial-warriors/.

Want to learn more?

Cyprus and Ugarit: A Tale of Two Late Bronze Age Mercantile Polities

When Is It Ok to Recycle a Coffin? The Rules of the Reuse Game in Ancient Egypt

Post a comment