Mesopotamia Murder Mystery

December 2022 | Vol. 10.12

By Virginia Verardi

Note: This report includes data derived from and images of human remains.

Archaeology recovers processes in the past, like the evolution of cities, as well as individual events, like dropped pots. But what if one of those events is murder?

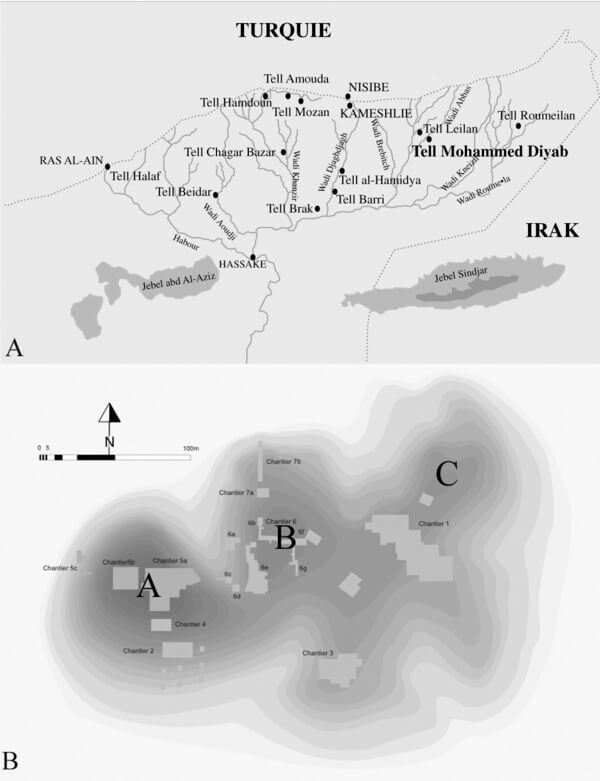

During the 2008 excavation campaign in the northern part of Tell Mohammed Diyab (located in northeastern Syria), we came across a strange feature, yet to be fully explained. During the study of construction phases of a domestic building, a circular irregularity appeared in the floor: in this area; some of the white stones composing the floor were missing. Then, while exploring what appeared to be a pit, we found two different skeletons, one on top of the other.

Map showing location of Tell Mohammed Diyab and plan of the site.

The good state of preservation of the bodies (both complete), allowed the staff anthropologist, Emilie Lemée, to carefully examine them. Her study revealed that both were males in their early to late twenties, The upper body (skeleton 1) was around 20-24 years old, as shown by the fact that the sternal extremity was not yet welded to the sternum. The lower body (skeleton 2) was older, around 20-29 years old; he had a broken left arm (radius + ulna) and he lacked the fingers of his right hand.

But the most intriguing element was the fact that the bodies seemed to have been simply discarded inside the pit and not carefully placed on their backs or sides as in a usual burial. The upper body was set on his back, with his arms spread to his sides, practically bent in two: the legs were over his torso, his feet reached head level. He appeared to have been thrown over a second body, which was placed on his right-hand side, arms spread in front of him, legs spread. The excavation of both bodies also revealed no weapons in the pit.

Pit with missing stone floor.

The evidence suggesting murder continued to mount when careful examination of the bodies also showed that at least the upper body of skeleton 1 had been stabbed, probably to death, since he bore traces of stab wounds on the sternum and on the 1st lumbar vertebra. He was therefore struck at least twice, once in the chest and once in the stomach. The second body did not show similar stab wounds, but his left hand seemed to have been mutilated, since it totally lacked the phalanges.

Apparently, the person who buried the bodies used an empty pit, probably a reused silo, to discard them and the pit was later covered by the floor of a house, after being filled with soil containing a few small objects. Was all this to conceal murders? And if so, when did they occur?

Skeletons being excavated.

The unusual context makes dating this group burial problematic, due to the scarcity of dating elements in the “grave” itself. One piece of evidence could be the layer that covered the floor in which the pit was dug, probably dating from the very beginning of the Mittanian period (second half of the second millennium BCE, the so-called the Old Jezirah 3, ca. 1700-1550 BCE or at the latest Middle Jezirah 1, ca. 1550-1300 BCE, in the North Syrian Chronology), the floor being the terminus ante quem. It is only a proposed date, since no C14 dating was done on the bone material before the start of the conflict in Syria made continuation of the research impossible.

The opening of the pit measured about 80 cm in diameter so it is highly probable that it is the top of the silo. Since the skeletons were found at the bottom, the silo must still have been in use at the time of the killing. And since the material found inside showed no trace of modern intrusions such as plastics, cloth or construction debris, it is highly improbable that the silo was still visible in modern times, especially since there appears to be a series of organized bricks blocking the mouth of the pit, that were set prior to the stone floor installation.

Skeleton with stab wound.

The material found in the pit was very scarce. There was a terracotta bull head, a small wheel, a miniature (and very crude) vase as well as an iron nail, a black “fritte” (glass) object and a few animal bones, mainly phalanges. This very sparse material does give some indication that helps the date of pit or its contents: both the crude vase and the boar head are covered in brownish-red lines, typical from the very late Habur period. They seem to date from the end of the period, thus the transition Middle Bronze Age-Late Bronze Age ca. 1550 BCE.

Strangely, there is another case of a body found under a floor at the same site. In another area of the mound, in area 3, a body was found under a collapsed wall that was later covered by a floor dating from the Mittanian period. This indicates a violent end to this stage of the three excavated houses in the areas. The presence of what seem to be sling balls seem to support the theory of military combat in this area.

But the main difference between this body and the two found in the pit is that in the latter case there are no traces of violence, so we cannot tell if it is a burial following a battle. The only likely explanation would therefore be a murder, that occurred sometimes around 1750-1550 BCE, and that was hidden by throwing the two corpses in a pit, that was later covered by a stone floor.

Hand with missing phalanges.

The identities of the bodies will, of course, almost certainly always elude us, since no texts regarding a murder that occurred on the site have been found in Tell Mohammed Diyab, Syria. The mystery endures.

Virginia Verardi is the Head of the Archaeology Department of the Val-de-Marne.

How to cite this article

Verardi, V. 2022. “Mesopotamia Murder Mystery.”The Ancient Near East Today 10.12. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/verardi-mesopotamia-murder-mystery/.

All images are courtesy of the Mission de Tell Mohammed Diyab : photos by V. Verardi and ©Mission de Tell Mohammed Diyab: drawings by V. Verardi. With thanks to Dr. Christophe Nicolle (CNRS) for permission to publish data, and spécial thanks to Emilie Lemée.

Want to learn more?

Cyprus and Ugarit: A Tale of Two Late Bronze Age Mercantile Polities

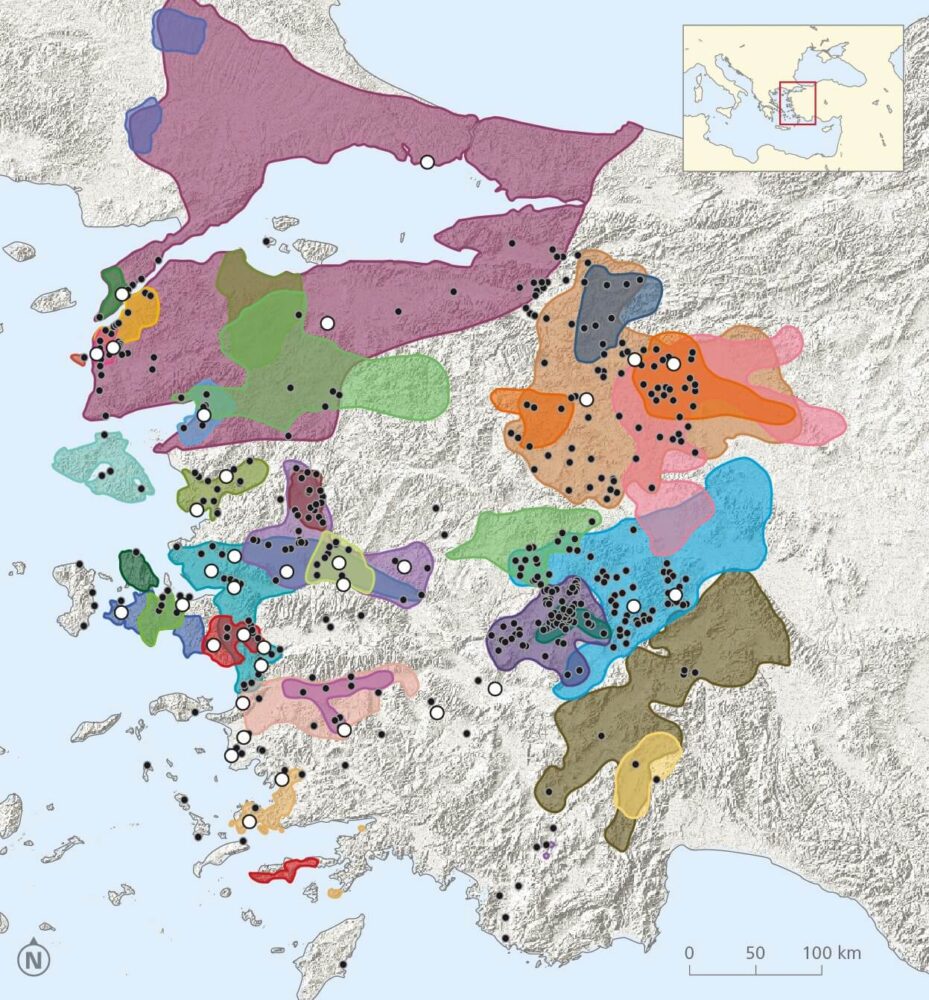

Processing Geospatial Data in Archaeology: Introducing LuwianSiteAtlas for Bronze Age Western Anatolia

Post a comment