Ancient Egyptian Food Prohibitions

August 2022 | Vol. 10.8

By Youri Volokhine

The topic of food prohibitions in ancient Egypt may be viewed from two perspectives, the Egyptian theological view about licit or illicit consumption, and the actual dietary practices in Egyptian society. Articulating these two types of evidence points to a significant gap between the realities of diet and discourses about food in Egypt.

The link between dietary restrictions and questions of identity has become a feature of academic debates. But the question of food prohibitions in ancient Egypt does not present itself as an identity issue, whereas this idea is embryonic in Greek thought. What is at stake in Egypt stems from a classification system specific to this civilization, a system proceeding from priestly norms which applies to the world of temples.

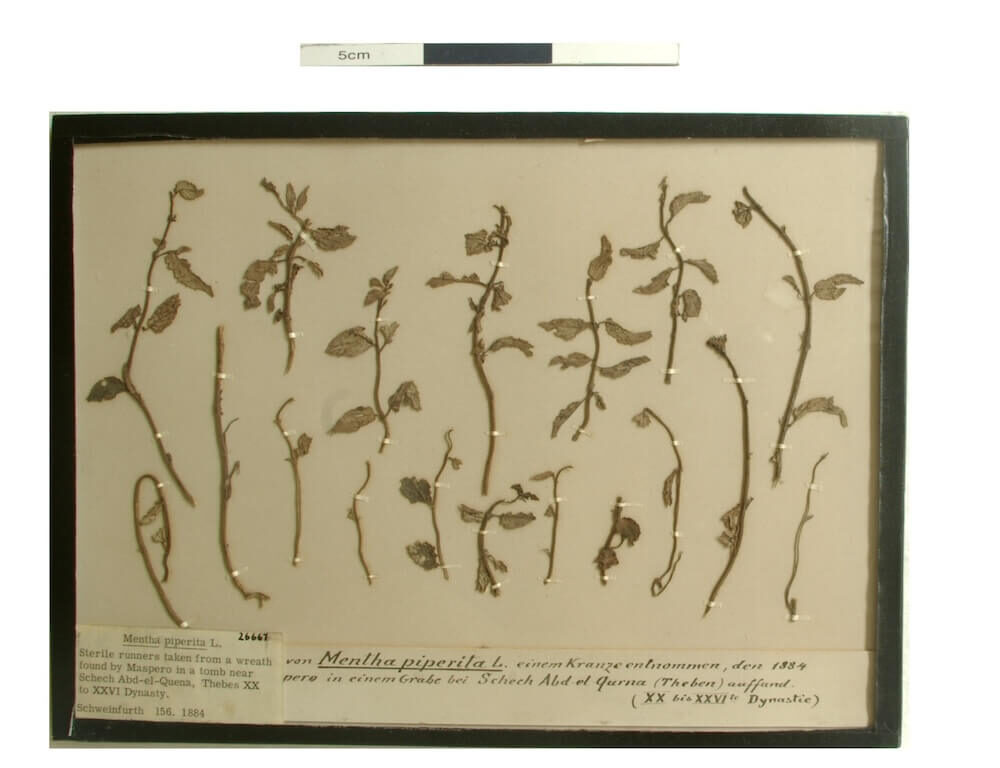

Negative prescriptions relating to food can be expressed in funerary texts, in liturgical calendars, or in inscriptions relating to religious geography. These recommendations do not allow us to imagine the existence of permanent food bans. Egyptian thought builds classification systems concerning animals and plants, which can, depending on the case, exclude this or that species from the diet. Such categories can be based on significantly different (but mainly symbolic) reasons which emanate from a socio-cultural perspective attributing to an animal a valued or disadvantaged position. Moreover, it often proceeds from priestly thought which defines categorical imperatives of purity and tends to eliminate impurity (outside the temple, the tomb, etc.) and all that is attached to it.

Figurine of a Wild Pig, Ptolemaic – Roman Period (323 – 30 BCE). LACMA M.80.198.11. Public domain.

Thus, all that we can know about food restrictions must be considered in specific contexts, including period, region and/or temple area. There are no food prohibitions with collective or permanent value in Pharaonic society, whatever the period. Nevertheless, there are specific restrictions, to which particular documents refer in given contexts.

It was the Greek authors who first reflected on Egyptian attitudes to food, noticing the exclusion of certain animals in particular circumstances. By pointing out these facts, the Greeks contributed to inventing the debate, situated from the beginning in a comparative context. We are still dependent on these discourses.

In Greek discourse, there was much interest in the priest, who was subject to strict prohibitions. Plutarch stated Egyptian priests abstained from legumes, mutton and pork because these foods give rise to an abundance of excrement. Take also the emblematic case of the pig. Herodotus (II, 47) teaches us that pork is impure (aneiros) in Egypt, and that this impurity would result in rejection, restricting the consumption of the animal to particular occasions. However, Herodotus also affirms that the animal is eaten, only within the specific framework of a lunar festival during which it is lawful to sacrifice it. A discourse thus emerged in Greek thought which positioned the idea of Egyptian repulsion towards pigs in comparative perspective with the practices of the Judeans.

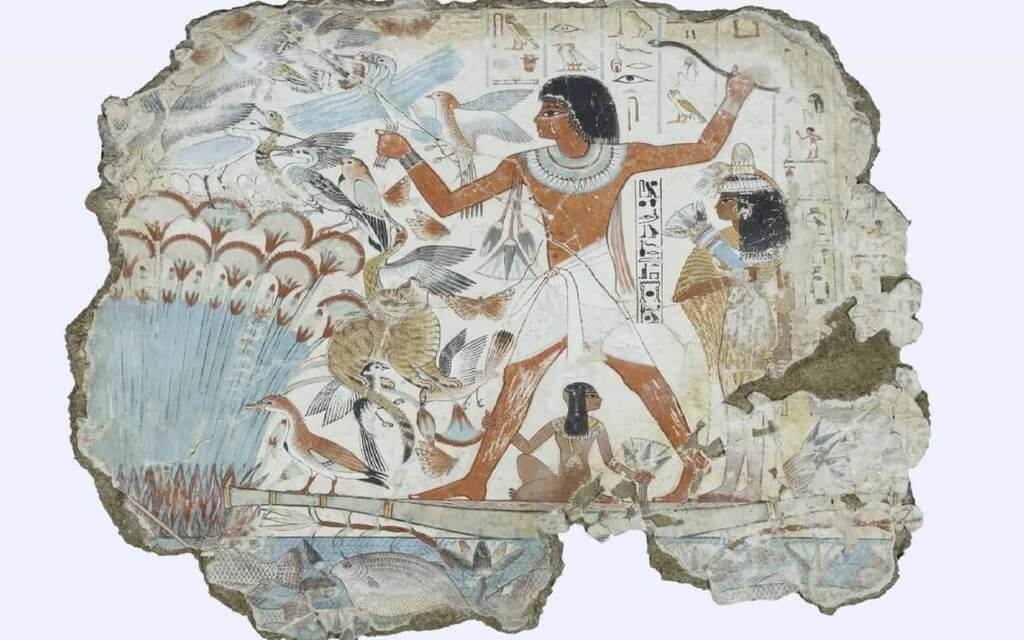

Birding scene. Tomb of Nebamun and his wife Hatshepsut. British Museum EA 37977. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The prohibition of pork among the Jews was an object of astonishment and questioning for the classical authors, all the more so since pigs were very popular in the Greco-Roman diet and were a common sacrificial animal. Several faults are presumed, by the Greeks, to be responsible for the food exclusion of pork. First, the pig consumes and excretes dirty matter, from which it draws its impurity. The pig also transmits skin diseases; the species itself is afflicted by it, and by contagion infects men. Sometimes this alleged prohibition was taken as an example of the cultural difference between Egyptians and Greeks.

In this framework we may to compare Egyptian practices with those of the Judeans. From the Greek point of view, Pharaonic customs do not differentiate between priestly uses and those of the people. Thus for Celsus (quoted in Origen), not only the priests, but indeed all Egyptians abstain not only from pork, but also from goat, sheep, beef and fish. Of course this was false. We therefore see that the classical tradition tends to maximize prohibitions in Egypt.

Egyptian religious discourse on the pure and the impure concerned what should be attached to the gods (that is, the world of temples and tombs), and what should, on the contrary, be removed from it. The term to qualify this notion of preservation of purity is bwt, that which must be removed from the temple, if not from the sight of the gods. This term has been translated as “taboo”, an exotic concept much favored by anthropology, but this does not reflect the reality of the Egyptian concept. What must be remembered is that the defect of impurity is not permanent; it is generally assigned in frameworks determined by priestly requirements. In the first place, excrement and garbage constitute the harmful pole of a symbolic diet, while bread, water and beer are, par excellence, favorable foods. This structured and polarized system proceeds from a particular dimension of food ideology, marking likes and dislikes, compatibilities and aberrations, likely to compromise a state of ritual purity. On the one hand, a food hierarchy must be observed. Fish (like pigs) are modest everyday food that does not fit the dignity of a prestigious meal. The agricultural hierarchy also places cattle in the lead, followed by goats, sheep, while pigs and donkeys bring up the rear.

Finally, ritual and/or funerary concerns sometimes involve setting aside certain foodstuffs (concerning in the first instance the king and the priests). Fish are most frequently mentioned in food exclusions, notwithstanding widespread consumption. In any case, food in Pharaonic Egypt depended on the social hierarchy; food of the court and the social elite was certainly more varied than food of the people.

Some religious texts hint at dietary restrictions including the New Kingdom Religious Ephemeris (Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days), the Ptolemaic lists summarizing the sacred items of the provinces, and specific enumerations of prohibitions (bwt) attested in Greco-Roman sources. In the New Kingdom lists the excluded species are relatively few – mostly different kinds of fish, a few plants, sometimes birds, which are excluded from the table on any given day. These food prohibitions also relate specifically to the first month of the Akhet season. We can therefore envisage a link between the flood season – that of beneficial renewal – and the obligation to withhold food from time to time (a selective diet).

Furthermore, we can imagine that the significant development of animal worship in the Late Period had significant consequences on food, because of the repercussions on the sacredness of an animal in local theology. Transient and local conditions certainly have an impact on food when species enter the edible category. But the impact of the prohibition on the population is difficult to apprehend since prohibitions concern first and foremost priests, then people who want to access part of the temple.

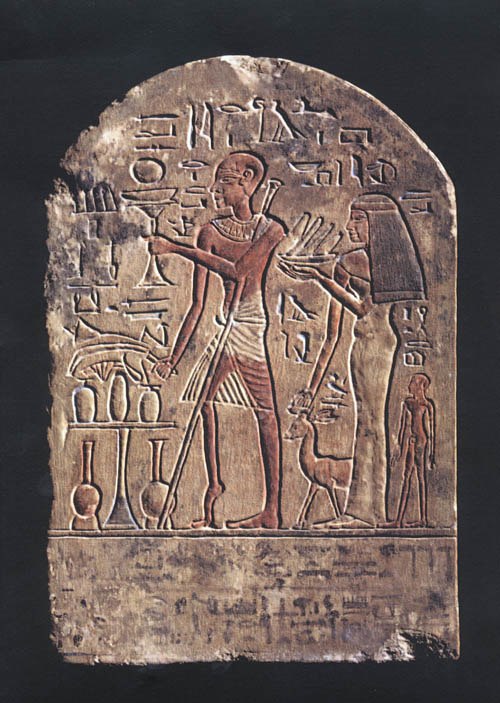

Horus and Seth crowning Ramses III. Early 12th century BC. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Image by A. Parrot via Wikimedia Commons. CC0.

On the question of pork, which reveals the complexity of the Egyptian system, we can observe that no explicit ban on the consumption of pork is formulated in the texts. The pig is clearly associated with a bwt aversion in the Middle Kingdom’s Coffin Texts. The pig is also generally excluded from the tables of offerings, except in special ritual circumstances, in XXth Dynasty and then Ptolemaic texts. Obviously pork provides a popular and very widely consumed meat, except that its association with lower value livestock keeps it out of higher class cuisine. The mythological bond between the male pig and the god Seth may also contribute to the animal eventually being despised in the priestly world. Nevertheless, no recommendation for the shunning of the animal is attested in the priestly monographs or elsewhere. On the contrary, the sacrificial killing of pigs for Sekhmet is mentioned in Ptolemaic texts. Ultimately, it should be noted that explicit mentions of dietary restrictions are infrequent. The question of food is not decisive or central to obtaining ritual purity. It can contribute to ritual purity, of course, but it is not the object of scrupulous attention.

Egyptian prohibitions concerning foods cross several fields of meaning: mythical thought (food of the gods or the deceased in the Beyond); priestly thought (imperatives linked to the theology of the nomes, purity constraints relating to access to the temple; food ideology (valuation and devaluation of species). But the sociological reality of food, which is partially determined by these prohibitions, is more difficult. Explicit sources are rare. Archaeozoology offers results that we can try to relate with the textual data, albeit with precautions. However, until now it has not been possible to confirm food prohibitions with archaeozoology, which, although particularly interesting, are linked to specific contexts.

Youri Volokhine is a faculty member in the Département Sciences de l’Antiquité at the Université de Genève.

How to cite this article

Volokhine, Y. 2022. “Ancient Egyptian Food Prohibitions.” The Ancient Near East Today 10.8. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/volokhine-egypt-food-prohibitions/.

Want to learn more?

When Is It Ok to Recycle a Coffin? The Rules of the Reuse Game in Ancient Egypt

Post a comment